Knowledge management

Knowledge management (KM) is the process of creating, sharing, using and managing the knowledge and information of an organisation.[1] It refers to a multidisciplinary approach to achieving organisational objectives by making the best use of knowledge.[2]

An established discipline since 1991, KM includes courses taught in the fields of business administration, information systems, management, library, and information sciences.[3][4] Other fields may contribute to KM research, including information and media, computer science, public health and public policy.[5] Several universities offer dedicated master's degrees in knowledge management.

Many large companies, public institutions and non-profit organisations have resources dedicated to internal KM efforts, often as a part of their business strategy, IT, or human resource management departments.[6] Several consulting companies provide advice regarding KM to these organisations.[6]

Knowledge management efforts typically focus on organisational objectives such as improved performance, competitive advantage, innovation, the sharing of lessons learned, integration and continuous improvement of the organisation.[7] These efforts overlap with organisational learning and may be distinguished from that by a greater focus on the management of knowledge as a strategic asset and on encouraging the sharing of knowledge.[2][8] KM is an enabler of organisational learning.[9][10]

Contents

History[edit]

Knowledge management efforts have a long history, including on-the-job discussions, formal apprenticeship, discussion forums, corporate libraries, professional training, and mentoring programs.[2][10] With increased use of computers in the second half of the 20th century, specific adaptations of technologies such as knowledge bases, expert systems, information repositories, group decision support systems, intranets, and computer-supported cooperative work have been introduced to further enhance such efforts.[2]

In 1999, the term personal knowledge management was introduced; it refers to the management of knowledge at the individual level.[11]

In the enterprise, early collections of case studies recognised the importance of knowledge management dimensions of strategy, process and measurement.[12][13] Key lessons learned include people and the cultural norms which influence their behaviors are the most critical resources for successful knowledge creation, dissemination and application; cognitive, social and organisational learning processes are essential to the success of a knowledge management strategy; and measurement, benchmarking and incentives are essential to accelerate the learning process and to drive cultural change.[13] In short, knowledge management programs can yield impressive benefits to individuals and organisations if they are purposeful, concrete and action-orientated.

Research[edit]

KM emerged as a scientific discipline in the early 1990s.[14] It was initially supported by individual practitioners, when Skandia hired Leif Edvinsson of Sweden as the world's first Chief Knowledge Officer (CKO).[15] Hubert Saint-Onge (formerly of CIBC, Canada), started investigating KM long before that.[2] The objective of CKOs is to manage and maximise the intangible assets of their organisations.[2] Gradually, CKOs became interested in practical and theoretical aspects of KM, and the new research field was formed.[16] The KM idea has been taken up by academics, such as Ikujiro Nonaka (Hitotsubashi University), Hirotaka Takeuchi (Hitotsubashi University), Thomas H. Davenport (Babson College) and Baruch Lev (New York University).[3][17]

In 2001, Thomas A. Stewart, former editor at Fortune magazine and subsequently the editor of Harvard Business Review, published a cover story highlighting the importance of intellectual capital in organisations.[18] The KM discipline has been gradually moving towards academic maturity.[2] First, is a trend toward higher cooperation among academics; single-author publications are less common. Second, the role of practitioners has changed.[16] Their contribution to academic research declined from 30% of overall contributions up to 2002, to only 10% by 2009.[19] Third, the number of academic knowledge management journals has been steadily growing, currently reaching 27 outlets.[20]

Multiple KM disciplines exist; approaches vary by author and school.[16][21] As the discipline matured, academic debates increased regarding theory and practice, including:

- Techno-centric with a focus on technology, ideally those that enhance knowledge sharing and creation.[22][23]

- Organisational with a focus on how an organisation can be designed to facilitate knowledge processes best.[6]

- Ecological with a focus on the interaction of people, identity, knowledge, and environmental factors as a complex adaptive system akin to a natural ecosystem.[24][25]

Regardless of the school of thought, core components of KM roughly include people/culture, processes/structure and technology. The details depend on the perspective.[26] KM perspectives include:

- community of practice[27]

- social network analysis[28]

- intellectual capital[29]

- information theory[14][15]

- complexity science[30]

- constructivism[31][32]

The practical relevance of academic research in KM has been questioned[33] with action research suggested as having more relevance[34] and the need to translate the findings presented in academic journals to a practice.[12]

Dimensions[edit]

Different frameworks for distinguishing between different 'types of' knowledge exist.[10] One proposed framework for categorising the dimensions of knowledge distinguishes tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge.[30] Tacit knowledge represents internalised knowledge that an individual may not be consciously aware of, such as to accomplish particular tasks. At the opposite end of the spectrum, explicit knowledge represents knowledge that the individual holds consciously in mental focus, in a form that can easily be communicated to others.[16][35]

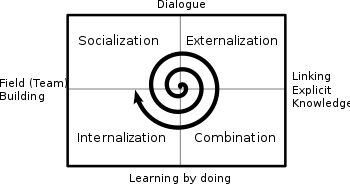

Ikujiro Nonaka proposed a model (SECI, for Socialisation, Externalisation, Combination, Internalisation) which considers a spiraling interaction between explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge.[36] In this model, knowledge follows a cycle in which implicit knowledge is 'extracted' to become explicit knowledge, and explicit knowledge is 're-internalised' into implicit knowledge.[36]

Hayes and Walsham (2003) describe knowledge and knowledge management as two different perspectives.[37] The content perspective suggests that knowledge is easily stored; because it may be codified, while the relational perspective recognises the contextual and relational aspects of knowledge which can make knowledge difficult to share outside the specific context in which it is developed.[37]

Early research suggested that KM needs to convert internalised tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge to share it, and the same effort must permit individuals to internalise and make personally meaningful any codified knowledge retrieved from the KM effort.[6][38]

Subsequent research suggested that a distinction between tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge represented an oversimplification and that the notion of explicit knowledge is self-contradictory.[11] Specifically, for knowledge to be made explicit, it must be translated into information (i.e., symbols outside our heads).[11][39] More recently, together with Georg von Krogh and Sven Voelpel, Nonaka returned to his earlier work in an attempt to move the debate about knowledge conversion forward.[4][40]

A second proposed framework for categorising knowledge dimensions distinguishes embedded knowledge of a system outside a human individual (e.g., an information system may have knowledge embedded into its design) from embodied knowledge representing a learned capability of a human body's nervous and endocrine systems.[41]

A third proposed framework distinguishes between the exploratory creation of "new knowledge" (i.e., innovation) vs. the transfer or exploitation of "established knowledge" within a group, organisation, or community.[37][42] Collaborative environments such as communities of practice or the use of social computing tools can be used for both knowledge creation and transfer.[42]

Strategies[edit]

Knowledge may be accessed at three stages: before, during, or after KM-related activities.[29] Organisations have tried knowledge capture incentives, including making content submission mandatory and incorporating rewards into performance measurement plans.[43] Considerable controversy exists over whether such incentives work and no consensus has emerged.[7]

One strategy to KM involves actively managing knowledge (push strategy).[7][44] In such an instance, individuals strive to explicitly encode their knowledge into a shared knowledge repository, such as a database, as well as retrieving knowledge they need that other individuals have provided (codification).[44]

Another strategy involves individuals making knowledge requests of experts associated with a particular subject on an ad hoc basis (pull strategy).[7][44] In such an instance, expert individual(s) provide insights to requestor (personalisation).[30]

Hansen et al. defined the two strategies.[45] Codification focuses on collecting and storing codified knowledge in electronic databases to make it accessible.[46] Codification can therefore refer to both tacit and explicit knowledge.[47] In contrast, personalisation encourages individuals to share their knowledge directly.[46] Information technology plays a less important role, as it is only facilitates communication and knowledge sharing.

Other knowledge management strategies and instruments for companies include:[7][24][30]

- Knowledge sharing (fostering a culture that encourages the sharing of information, based on the concept that knowledge is not irrevocable and should be shared and updated to remain relevant)

- Make knowledge-sharing a key role in employees' job description

- Inter-project knowledge transfer

- Intra-organisational knowledge sharing

- Inter-organisational knowledge sharing

- Proximity & architecture (the physical situation of employees can be either conducive or obstructive to knowledge sharing)

- Storytelling (as a means of transferring tacit knowledge)

- Cross-project learning

- After-action reviews

- Knowledge mapping (a map of knowledge repositories within a company accessible by all)

- Communities of practice

- Expert directories (to enable knowledge seeker to reach to the experts)

- Expert systems (knowledge seeker responds to one or more specific questions to reach knowledge in a repository)

- Best practice transfer

- Knowledge fairs

- Competence management (systematic evaluation and planning of competences of individual organisation members)

- Master–apprentice relationship, Mentor-mentee relationship, job shadowing

- Collaborative software technologies (wikis, shared bookmarking, blogs, social software, etc.)

- Knowledge repositories (databases, bookmarking engines, etc.)

- Measuring and reporting intellectual capital (a way of making explicit knowledge for companies)

- Knowledge brokers (some organisational members take on responsibility for a specific "field" and act as first reference on a specific subject)

Motivations[edit]

Multiple motivations lead organisations to undertake KM.[35] Typical considerations include:[30]

- Making available increased knowledge content in the development and provision of products and services

- Achieving shorter development cycles

- Facilitating and managing innovation and organisational learning

- Leveraging expertises across the organisation

- Increasing network connectivity between internal and external individuals

- Managing business environments and allowing employees to obtain relevant insights and ideas appropriate to their work

- Solving intractable or wicked problems

- Managing intellectual capital and assets in the workforce (such as the expertise and know-how possessed by key individuals or stored in repositories)

KM technologies[edit]

Knowledge management (KM) technology can be categorised:

- Groupware—Software that facilitates collaboration and sharing of organisational information. Such applications provide tools for threaded discussions, document sharing, organisation-wide uniform email, and other collaboration-related features.

- Workflow systems—Systems that allow the representation of processes associated with the creation, use and maintenance of organisational knowledge, such as the process to create and utilise forms and documents.

- Content management and document management systems—Software systems that automate the process of creating web content and/or documents. Roles such as editors, graphic designers, writers and producers can be explicitly modeled along with the tasks in the process and validation criteria. Commercial vendors started either to support documents or to support web content but as the Internet grew these functions merged and vendors now perform both functions.

- Enterprise portals—Software that aggregates information across the entire organisation or for groups such as project teams.

- eLearning—Software that enables organisations to create customised training and education. This can include lesson plans, monitoring progress and online classes.

- Planning and scheduling software—Software that automates schedule creation and maintenance. The planning aspect can integrate with project management software.[22]

- Telepresence—Software that enables individuals to have virtual "face-to-face" meetings without assembling at one location. Videoconferencing is the most obvious example.

These categories overlap. Workflow, for example, is a significant aspect of a content or document management systems, most of which have tools for developing enterprise portals.[7][48]

Proprietary KM technology products such as Lotus Notes defined proprietary formats for email, documents, forms, etc. The Internet drove most vendors to adopt Internet formats. Open-source and freeware tools for the creation of blogs and wikis now enable capabilities that used to require expensive commercial tools.[34][49]

KM is driving the adoption of tools that enable organisations to work at the semantic level,[50] as part of the Semantic Web.[51] Some commentators have argued that after many years the Semantic Web has failed to see widespread adoption,[52][53][54] while other commentators have argued that it has been a success.[55]

See also[edit]

- Archives management

- Customer knowledge

- Dynamic knowledge repository

- Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management

- Ignorance management

- Information governance

- Information management

- Journal of Knowledge Management

- Journal of Knowledge Management Practice

- Knowledge cafe

- Knowledge community

- Knowledge ecosystem

- Knowledge engineering

- Knowledge management software

- Knowledge modeling

- Knowledge transfer

- Knowledge translation

- Legal case management

References[edit]

- ^ Girard, John P.; Girard, JoAnn L. (2015). "Defining knowledge management: Toward an applied compendium" (PDF). Online Journal of Applied Knowledge Management. 3 (1): 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Introduction to Knowledge Management". www.unc.edu. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on March 19, 2007. Retrieved 11 September 2014.CS1 maint: Unfit url (link)

- ^ a b Nonaka, Ikujiro (1991). "The knowledge creating company". Harvard Business Review. 69 (6): 96–104.

- ^ a b Nonaka, Ikujiro; von Krogh, Georg (2009). "Tacit Knowledge and Knowledge Conversion: Controversy and Advancement in Organizational Knowledge Creation Theory". Organization Science. 20 (3): 635–652. doi:10.1287/orsc.1080.0412.

- ^ Bellinger, Gene. "Mental Model Musings". Systems Thinking Blog. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d Addicot, Rachael; McGivern, Gerry; Ferlie, Ewan (2006). "Networks, Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management: NHS Cancer Networks". Public Money & Management. 26 (2): 87–94. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9302.2006.00506.x.

- ^ a b c d e f Gupta, Jatinder; Sharma, Sushil (2004). Creating Knowledge Based Organizations. Boston: Idea Group Publishing. ISBN 1-59140-163-1.

- ^ Maier, R. (2007). Knowledge Management Systems: Information And Communication Technologies for Knowledge Management (3rd edition). Berlin: Springer.

- ^ Sanchez, R (1996) Strategic Learning and Knowledge Management, Wiley, Chichester

- ^ a b c Sanchez, R. (1996). Strategic Learning and Knowledge Management. Chichester: Wiley.

- ^ a b c Wright, Kirby (2005). "Personal knowledge management: supporting individual knowledge worker performance". Knowledge Management Research and Practice. 3 (3): 156–165. doi:10.1057/palgrave.kmrp.8500061.

- ^ a b Booker, Lorne; Bontis, Nick; Serenko, Alexander (2008). "The relevance of knowledge management and intellectual capital research" (PDF). Knowledge and Process Management. 15 (4): 235–246. doi:10.1002/kpm.314.

- ^ a b Morey, Daryl; Maybury, Mark; Thuraisingham, Bhavani (2002). Knowledge Management: Classic and Contemporary Works. MIT Press. p. 451. ISBN 0-262-13384-9.

- ^ a b McInerney, Claire (2002). "Knowledge Management and the Dynamic Nature of Knowledge". Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 53 (12): 1009–1018. doi:10.1002/asi.10109.

- ^ a b "Information Architecture and Knowledge Management". Kent State University. Archived from the original on June 29, 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d Bray, David. "SSRN-Literature Review – Knowledge Management Research at the Organizational Level". Papers.ssrn.com. SSRN 991169. Missing or empty

|url=(help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Davenport, Tom. "Enterprise 2.0: The New, New Knowledge Management?". Harvard Business Review. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Stewart, Thomas A. (1998). Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth of Organizations. Crown Business Publishers. ISBN 0385483813.

- ^ Serenko, Alexander; Bontis, Nick; Booker, Lorne; Sadeddin, Khaled; Hardie, Timothy (2010). "A scientometric analysis of knowledge management and intellectual capital academic literature (1994–2008)" (PDF). Journal of Knowledge Management. 14 (1): 13–23. doi:10.1108/13673271011015534.

- ^ Serenko, Alexander; Bontis, Nick (2017). "Global Ranking of Knowledge Management and Intellectual Capital Academic Journals: 2017 Update" (PDF). Journal of Knowledge Management. 21 (3): 675–692. doi:10.1108/JKM-11-2016-0490.

- ^ Langton Robbins, N. S. (2006). Organizational Behaviour (Fourth Canadian Edition). Toronto, Ontario: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- ^ a b Alavi, Maryam; Leidner, Dorothy E. (1999). "Knowledge management systems: issues, challenges, and benefits". Communications of the AIS. 1 (2).

- ^ Rosner, D.; Grote, B.; Hartman, K.; Hofling, B.; Guericke, O. (1998). "From natural language documents to sharable product knowledge: a knowledge engineering approach". In Borghoff, Uwe M.; Pareschi, Remo. Information technology for knowledge management. Springer Verlag. pp. 35–51.

- ^ a b Bray, David. "SSRN-Knowledge Ecosystems: A Theoretical Lens for Organizations Confronting Hyperturbulent Environments". Papers.ssrn.com. SSRN 984600. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ^ Carlson Marcu Okurowsk, Lynn; Marcu, Daniel; Okurowsk, Mary Ellen. "Building a Discourse-Tagged Corpus in the Framework of Rhetorical Structure Theory" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Spender, J.-C.; Scherer, A. G. (2007). "The Philosophical Foundations of Knowledge Management: Editors' Introduction". Organization. 14 (1): 5–28. doi:10.1177/1350508407071858. SSRN 958768.

- ^ "TeacherBridge: Knowledge Management in Communities of Practice" (PDF). Virginia Tech. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Groth, Kristina. "Using social networks for knowledge management" (PDF). Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ a b Bontis, Nick; Choo, Chun Wei (2002). The Strategic Management of Intellectual Capital and Organizational Knowledge. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513866-X.

- ^ a b c d e Snowden, Dave (2002). "Complex Acts of Knowing – Paradox and Descriptive Self Awareness". Journal of Knowledge Management, Special Issue. 6 (2): 100–111. doi:10.1108/13673270210424639.

- ^ Nanjappa, Aloka; Grant, Michael M. (2003). "Constructing on constructivism: The role of technology" (PDF). Electronic Journal for the Integration of Technology in Education. 2 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17.

- ^ Wyssusek, Boris. "Knowledge Management - A Sociopragmatic Approach (2001)". CiteSeerX. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Ferguson, J. (2005). "Bridging the gap between research and practice". Knowledge Management for Development Journal. 1 (3): 46–54.

- ^ a b Andriessen, Daniel (2004). "Reconciling the rigor-relevance dilemma in intellectual capital research". The Learning Organization. 11 (4/5): 393–401. doi:10.1108/09696470410538288.

- ^ a b Alavi, Maryam; Leidner, Dorothy E. (2001). "Review: Knowledge Management and Knowledge Management Systems: Conceptual Foundations and Research Issues". MIS Quarterly. 25 (1): 107–136. doi:10.2307/3250961. JSTOR 3250961.

- ^ a b Nonaka, Ikujiro; Takeuchi, Hirotaka (1995). The knowledge creating company: how Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-19-509269-1.

- ^ a b c Hayes, M.; Walsham, G. (2003). "Knowledge sharing and ICTs: A relational perspective". In Easterby-Smith, M.; Lyles, M.A. The Blackwell Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management. Malden, MA: Blackwell. pp. 54–77. ISBN 978-0-631-22672-7.

- ^ "Rhetorical Structure Theory Website". RST. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Serenko, Alexander; Bontis, Nick (2004). "Meta-review of knowledge management and intellectual capital literature: citation impact and research productivity rankings" (PDF). Knowledge and Process Management. 11 (3): 185–198. doi:10.1002/kpm.203. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-26.

- ^ Nonaka, I.; von Krogh, G. & Voelpel S. (2006). "Organizational knowledge creation theory: Evolutionary paths and future advances" (PDF). Organization Studies. 27 (8): 1179–1208. doi:10.1177/0170840606066312.

- ^ Sensky, Tom (2002). "Knowledge Management". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 8 (5): 387–395. doi:10.1192/apt.8.5.387.

- ^ a b "SSRN-Exploration, Exploitation, and Knowledge Management Strategies in Multi-Tier Hierarchical Organizations Experiencing Environmental Turbulence by David Bray". Papers.ssrn.com. SSRN 961043. Missing or empty

|url=(help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Benbasat, Izak; Zmud, Robert (1999). "Empirical research in information systems: The practice of relevance". MIS Quarterly. 23 (1): 3–16. doi:10.2307/249403. JSTOR 249403.

- ^ a b c "Knowledge Management for Data Interoperability" (PDF). Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Hansen et al., 1999

- ^ a b Smith (2004), p. 7

- ^ Hall (2006), pp. 119f

- ^ Rao, Madanmohan (2005). Knowledge Management Tools and Techniques. Elsevier. pp. 3–42. ISBN 0-7506-7818-6.

- ^ Calvin, D. Andrus (2005). "The Wiki and the Blog: Toward a Complex Adaptive Intelligence Community". Studies in Intelligence. 49 (3). SSRN 755904.

- ^ Capozzi, Marla M. (2007). "Knowledge Management Architectures Beyond Technology". First Monday. 12 (6). doi:10.5210/fm.v12i6.1871.

- ^ Berners-Lee, Tim; Hendler, James; Lassila, Ora (May 17, 2001). "The Semantic Web A new form of Web content that is meaningful to computers will unleash a revolution of new possibilities". Scientific American. 284: 34–43. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0501-34. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013.

- ^ Bakke, Sturla; ygstad, Bendik (May 2009). "Two emerging technologies: a comparative analysis of Web 2.0 and the Semantic Web". CONF-IRM 2009 Proceedings (28).

Our research question is: how do we explain the surprising success of Web 2.0 and the equally surprising non-fulfillment of the Semantic Web. Building on a case study approach we conducted a in depth comparative analysis of the two emerging technologies. We propose two conclusions. First, traditional top-down management of an emerging global technology has proved not to be effective in the case of the Semantic Web and Web 2.0, and second, the success for such global technologies is mainly associated with bootstrapping an already installed base.

- ^ Grimes, Seth (7 January 2014). "Semantic Web business: going nowhere slowly". InformationWeek. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

SemWeb is a narrowly purposed replica of a subset of the World Wide Web. It's useful for information enrichment in certain domains, via a circumscribed set of tools. However, the SemWeb offers a vanishingly small benefit to the vast majority of businesses. The vision persists but is unachievable; the business reality of SemWeb is going pretty much nowhere.

- ^ Cagle, Kurt (3 July 2016). "Why the Semantic Web has failed". LinkedIn. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

This may sound like heresy, but my personal belief is that the semantic web has failed. Not in "just give it a few more years and it'll catch on" or "it's just a matter of tooling and editors". No, I'd argue that, as admirable as the whole goal of the semantic web is, it's just not working in reality.

- ^ Zaino, Jennifer (23 September 2014). "The Semantic Web's rocking, and there ain't no stopping it now". dataversity.net. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

Make no mistake about it: The semantic web has been a success and that's not about to stop now. That was essentially the message delivered by W3C Data Activity Lead Phil Archer, during his keynote address celebrating the semantic web's ten years of achievement at last month's Semantic Technology & Business Conference in San Jose.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Knowledge management |

Media related to Knowledge management at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Knowledge management at Wikimedia Commons- Knowledge management at Curlie