Dravya

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

Jain prayers |

|

Ethics |

|

Major sects |

|

Festivals |

|

|

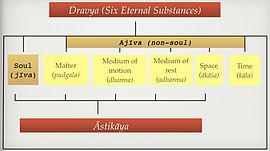

Dravya (Hindi: द्रव्य) is a term used to refer to a substance. According to the Jain philosophy, the universe is made up of six eternal substances: sentient beings or souls (jīva), non-sentient substance or matter (pudgala), principle of motion (dharma), the principle of rest (adharma), space (ākāśa) and time (kāla).[1][2] The latter five are united as the ajiva (the non-living). As per the Sanskrit etymology, dravya means substances or entity, but it may also mean real or fundamental categories.[2]

Jain philosophers distinguish a substance from a body, or thing, by declaring the former as a simple element or reality while the latter as a compound of one or more substances or atoms. They claim that there can be a partial or total destruction of a body or thing, but no substance can ever be destroyed. [3]

Contents

Jīva (living entity)[edit]

According to Jain philosophy, this universe consists of infinite jivas or souls that are uncreated and always existing. There are two main categories of souls: un-liberated mundane embodied souls that are still subject to transmigration and rebirths in this samsara due to karmic bondage and the liberated souls that are free from birth and death. All souls are intrinsically pure but are found in bondage with karma since beginning-less time. A soul has to make efforts to eradicate the karmas attain its true and pure form.

10th-century Jain monk Nemichandra describes the soul in Dravyasamgraha:[4]

The sentient substance (soul) is characterized by the function of understanding, is incorporeal, performs actions (doer), is co-extensive with its own body. It is the enjoyer (of its actions), located in the world of rebirth (samsara) (or) emancipated (moksa) (and) has the intrinsic movement upwards.

— Dravyasaṃgraha (2)

The qualities of the soul are chetana (consciousness) and upyoga (knowledge and perception). Though the soul experiences both birth and death, it is neither really destroyed nor created. Decay and origin refer respectively to the disappearing of one state and appearing of another state and these are merely the modes of the soul. Thus Jiva with its attributes and modes, roaming in samsara (universe), may lose its particular form and assume a new one. Again this form may be lost and the original acquired.[5]

Ajiva (five non-living entities)[edit]

Pudgala (Matter)[edit]

Matter is classified as solid, liquid, gaseous, energy, fine Karmic materials and extra-fine matter i.e. ultimate particles. Paramāṇu or ultimate particle (atoms or sub-atomic particles) is the basic building block of all matter. It possesses at all times four qualities, namely, a color (varna), a taste (rasa), a smell (gandha), and a certain kind of palpability (sparsha, touch).[6] One of the qualities of the paramāṇu and pudgala is that of permanence and indestructibility. It combines and changes its modes but its basic qualities remain the same.[7] It cannot be created nor destroyed and the total amount of matter in the universe remains the same.

Dharma[edit]

Dharma means the principles of Motion that pervade the entire universe. Dharma and Adharma are by themselves not motion or rest but mediate motion and rest in other bodies. Without Dharma motion is not possible. The medium of motion helps matter and the sentient that are prone to motion to move, like water (helps) fish. However, it does not set in motion those that do not move.[8]

Adharma[edit]

Without adharma, rest and stability is not possible in the universe. The principle of rest helps matter and the sentient that are liable to stay without moving, like the shade helps travellers. It does not stabilize those that move.[9] According to Champat Rai Jain:

The necessity of Adharma as the accompanying cause of rest, that is, of cessation of motion will be clearly perceived by any one who will put to himself the question, how jīvas and bodies of matter support themselves when coming to rest from a state of motion. Obviously gravitation will not do, for that is concerned with the determination of the direction which a moving body may take...[10]

Ākāśa (space)[edit]

Space is a substance that accommodates the living souls, the matter, the principle of motion, the principle of rest and time. It is all-pervading, infinite and made of infinite space-points.[11]

Kāla (time)[edit]

Kāla is a real entity according to Jainism and is said to be the cause of continuity and succession. Champat Rai Jain in his book "The Key of Knowledge wrote:[10]

...As a substance which assists other things in performing their ‘temporal’ gyrations, Time can be conceived only in the form of whirling posts. That these whirling posts, as we have called the units of Time, cannot, in any manner, be conceived as parts of the substances that revolve around them, is obvious from the fact that they are necessary for the continuance of all other substances, including souls and atoms of matter which are simple ultimate units, and cannot be imagined as carrying a pin each to revolve upon. Time must, therefore, be considered as a separate substance which assists other substances and things in their movements of continuity.

Jaina philosophers call the substance of Time as Niścay Time to distinguish it from vyavhāra (practical) Time which is a measure of duration- hours, days and the like.[10]

Astikaya[edit]

Out of the six dravyas, five except time have been described as astikayas, that is, extensions or conglomerates. Since like conglomerates, they have numerous space points, they are described as astikaya. There are innumerable space points in the sentient substance and in the media of motion and rest, and infinite ones in space; in matter they are threefold (i.e. numerable, innumerable and infinite). Time has only one; therefore it is not a conglomerate.[12] Hence the corresponding conglomerates or extensions are called—jivastikaya (soul extension or conglomerate), pudgalastikaya (matter conglomerate), dharmastikaya (motion conglomerate), adharmastikaya (rest conglomerate) and akastikaya (space conglomerates). Together they are called pancastikaya or the five astikayas.[13]

Attributes of Dravya[edit]

These substances have some common attributes or gunas such as:[14]

- Astitva (existence): indestructibility; permanence; the capacity by which a substance cannot be destroyed.

- Vastutva (functionality): capacity by which a substance has function.

- Dravyatva (changeability): capacity by which it is always changing in modifications.

- Prameyatva (knowability): capacity by which it is known by someone, or of being the subject-matter of knowledge.

- Agurulaghutva (individuality): capacity by which one attribute or substance does not become another and the substance does not lose the attributes whose grouping forms the substance itself.

- Pradeshatva (spatiality): capacity of having some kind of location in space.

There are some specific attributes that distinguish the dravyas from each other:[14]

- Chetanatva (consciousness) and amurtavta (immateriality) are common attributes of the class of substances soul or jiva.

- Achetanatva (non-consciousness) and murtatva (materiality) are attributes of matter.

- Achetanatva (non-consciousness) and amurtavta (immateriality) are common to Motion, Rest, Time and Space.

See also[edit]

- Tattva

- Dravyasamgraha — 10th-century Jain text

References[edit]

- ^ Acarya Nemicandra; Nalini Balbir (2010) p. 1 of Introduction

- ^ a b Grimes, John (1996). Pp.118–119

- ^ Champat Rai Jain 1917, p. 15.

- ^ Acarya Nemicandra; Nalini Balbir (2010) p. 4

- ^ Nayanar, Prof. A. Chakravarti (2005). verses 16–21

- ^ Jaini 1998, p. 90.

- ^ Grimes, John (1996). p. 249

- ^ Acarya Nemicandra; Nalini Balbir (2010) p.10

- ^ Acarya Nemicandra; Nalini Balbir (2010) p.11

- ^ a b c Jain, Champat Rai (1975). The Key Of Knowledge (Third ed.). New Delhi: Today and Tomorrow's Printers. p. 520–530.

- ^ Acarya Nemicandra; Nalini Balbir (2010) p.11–12

- ^ Acarya Nemicandra; Nalini Balbir (2010) p.12–13

- ^ J. C. Sikdar (2001) p. 1107

- ^ a b Acarya Nemicandra; J. L. Jaini (1927) p. 4 (of introduction)

Bibliography[edit]

- Acarya Nemicandra; Nalini Balbir (2010), Dravyasamgrha: Exposition of the Six Substances, Pandit Nathuram Premi Research Series (vol-19) (in Prakrit and English), Mumbai: Hindi Granth Karyalay, ISBN 978-81-88769-30-8CS1 maint: Unrecognized language (link)

- Nayanar, Prof. A. Chakravarti (2005), Pañcāstikāyasāra of Ācārya Kundakunda, New Delhi: Today & Tomorrows Printer and Publisher, ISBN 81-7019-436-9

- Sikdar, J. C. (2001), "Concept of matter", in (ed.) Nagendra Kr. Singh, Encyclopedia of Jainism, New Delhi: Anmol Publications, ISBN 81-261-0691-3CS1 maint: Extra text: editors list (link)

- Grimes, John (1996), A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English, New York: SUNY Press, ISBN 0-7914-3068-5

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1998) [1979], The Jaina Path of Purification, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1578-5

- Champat Rai Jain (1917), The Practical Path, The Central Jaina Publishing House

- Jacobi, Hermann (1884), (ed.) F. Max Müller, ed., The Ācāranga Sūtra, Sacred Books of the East vol.22, Part 1, Oxford: The Clarendon Press, ISBN 0-7007-1538-XCS1 maint: Extra text: editors list (link) Note: ISBN refers to the UK:Routledge (2001) reprint. URL is the scan version of the original 1884 reprint.