History of religion

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The history of religion refers to the written record of human religious experiences and ideas. This period of religious history begins with the invention of writing about 5,200 years ago (3200 BCE).[1] The prehistory of religion involves the study of religious beliefs that existed prior to the advent of written records. One can also study comparative religious chronology through a timeline of religion. Writing played a major role in standardizing religious texts regardless of time or location, and making easier the memorization of prayers and divine rules. The case of the Bible involves the collation of multiple oral texts handed down over the centuries.[2]

The concept of "religion" was formed in the 16th and 17th centuries,[3][4] despite the fact that ancient sacred texts like the Bible, the Quran, and others did not have a word or even a concept of religion in the original languages and neither did the people or the cultures in which these sacred texts were written.[5][6]

The word "religion" as used in the 21st century does not have an obvious pre-colonial translation into non-European languages. The anthropologist Daniel Dubuisson writes that "what the West and the history of religions in its wake have objectified under the name 'religion' is ... something quite unique, which could be appropriate only to itself and its own history".[7] The history of other cultures' interaction with the "religious" category is therefore their interaction with an idea that first developed in Europe under the influence of Christianity.[8][need quotation to verify]

Contents

History of study[edit]

The school of religious history called the Religionsgeschichtliche Schule, a late 19th-century German school of thought, originated the systematic study of religion as a socio-cultural phenomenon. It depicted religion as evolving with human culture, from primitive polytheism to ethical monotheism.

The Religionsgeschichtliche Schule emerged at a time when scholarly study of the Bible and of church history flourished in Germany and elsewhere (see higher criticism, also called the historical-critical method). The study of religion is important: religion and similar concepts have often shaped civilizations' law and moral codes, social structure, art and music.

Overview[edit]

The 19th century saw a dramatic increase in knowledge about a wide variety of cultures and religions, and also the establishment of economic and social histories of progress. The "history of religions" school sought to account for this religious diversity by connecting it with the social and economic situation of a particular group.

Typically, religions were divided into stages of progression from simple to complex societies, especially from polytheistic to monotheistic and from extempore to organized. One can also classify religions as circumcising and non-circumcising, proselytizing (attempting to convert people of other religion) and non-proselytizing. Many religions share common beliefs.

Origin[edit]

The earliest evidence of religious ideas dates back several hundred thousand years to the Middle and Lower Paleolithic periods. Archaeologists refer to apparent intentional burials of early Homo sapiens from as early as 300,000 years ago as evidence of religious ideas. Other evidence of religious ideas include symbolic artifacts from Middle Stone Age sites in Africa. However, the interpretation of early paleolithic artifacts, with regard to how they relate to religious ideas, remains controversial. Archeological evidence from more recent periods is less controversial. Scientists([which?] generally interpret a number of artifacts from the Upper Paleolithic (50,000-13,000 BCE) as representing religious ideas. Examples of Upper Paleolithic remains associated with religious beliefs include the lion man, the Venus figurines, cave paintings from Chauvet Cave and the elaborate ritual burial from Sungir.

In the 19th century researchers proposed various theories regarding the origin of religion, challenging earlier claims of a Christianity-like urreligion. Early theorists Edward Burnett Tylor (1832-1917) and Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) proposed the concept of animism, while archaeologist John Lubbock (1834-1913) used the term "fetishism". Meanwhile, religious scholar Max Müller (1823-1900) theorized that religion began in hedonism and folklorist Wilhelm Mannhardt (1831-1880) suggested that religion began in "naturalism", by which he meant mythological explanation of natural events.[9][page needed] All of these theories have since been widely criticized; there is no broad consensus regarding the origin of religion.

Pre-pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) Göbekli Tepe, the oldest religious site yet discovered anywhere[10] includes circles of erected massive T-shaped stone pillars, the world's oldest known megaliths [11] decorated with abstract, enigmatic pictograms and carved animal reliefs. The site, near the home place of original wild wheat, was built before the so-called Neolithic Revolution, i.e., the beginning of agriculture and animal husbandry around 9000 BCE. But the construction of Göbekli Tepe implies organization of an advanced order not hitherto associated with Paleolithic, PPNA, or PPNB societies. The site, abandoned around the time the first agricultural societies started, is still being excavated and analyzed, and thus might shed light to the significance it had had for the region's older, foraging communities, as well as for the general history of religions.

The Pyramid Texts from ancient Egypt are the oldest known religious texts in the world, dating to between 2400-2300 BCE.[12][13]

Surviving early copies of complete religious texts include:

The Dead Sea Scrolls, representing complete texts of the Hebrew Tanakh; these scrolls were copied approximately 2000 years ago.

Complete Hebrew texts, also of the Tanakh, but translated into the Greek language (Septuagint 300-200 BC), were in wide use by the early 1st century CE.

Advantages of religion[edit]

Organized religion emerged as a means of providing social and economic stability to large populations through the following ways:

- Organized religion served to justify a central authority, which in turn possessed the right to collect taxes in return for providing social and security services to the state. The empires of India and Mesopotamia were theocracies, with chiefs, kings and emperors playing dual roles of political and spiritual leaders.[14] Virtually all state societies and chiefdoms around the world have similar political structures where political authority is justified by divine sanction.

- Organized religion emerged as means of maintaining peace between unrelated individuals. Bands and tribes consist of small number of related individuals. However states and nations include thousands or millions of unrelated individuals. Jared Diamond argues that organized religion served to provide a bond between unrelated individuals who would otherwise be more prone to enmity. He argues that a leading cause of death among band and tribal societies is murder.[15]

Axial age[edit]

Historians have labelled the period from 900 to 200 BCE as the "axial age", a term coined by German-Swiss philosopher Karl Jaspers (1883-1969). According to Jaspers, in this era of history "the spiritual foundations of humanity were laid simultaneously and independently... And these are the foundations upon which humanity still subsists today." Intellectual historian Peter Watson has summarized this period as the foundation time of many of humanity's most influential philosophical traditions, including monotheism in Persia and Canaan, Platonism in Greece, Buddhism and Jainism in India, and Confucianism and Taoism in China. These ideas would become institutionalized in time - note for example Ashoka's role in the spread of Buddhism, or the role of platonic philosophy in Christianity at its foundation.

The historical roots of Jainism in India date back to the 9th-century BCE with the rise of Parshvanatha and his non-violent philosophy.[16][17][need quotation to verify]

Middle Ages[edit]

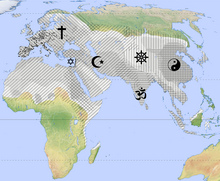

World religions of the present day established themselves throughout Eurasia during the Middle Ages by:

- Christianization of the Western world

- Buddhist missions to East Asia

- the decline of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent

- the spread of Islam throughout the Middle East, Central Asia, North Africa and parts of Europe and India

During the Middle Ages, Muslims came into conflict with Zoroastrians during the Islamic conquest of Persia (633-654); Christians fought against Muslims during the Byzantine-Arab Wars (7th to 11th centuries), the Crusades (1095 onward), the Reconquista (718-1492), the Ottoman wars in Europe (13th century onwards) and the Inquisition; Shamanism was in conflict with Buddhists, Taoists, Muslims and Christians during the Mongol invasions (1206-1337); and Muslims clashed with Hindus and Sikhs during the Muslim conquest of the Indian subcontinent (8th to 16th centuries).

Many medieval religious movements emphasized mysticism, such as the Cathars and related movements in the West, the Jews in Spain (see Zohar), the Bhakti movement in India and Sufism in Islam. Monotheism reached definite forms in Christian Christology and in Islamic Tawhid. Hindu monotheist notions of Brahman likewise reached their classical form with the teaching of Adi Shankara (788-820).

Modern period[edit]

European colonisation during the 15th to 19th centuries resulted in the spread of Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa, and to the Americas, Australia and the Philippines. The invention of the printing press in the 15th century played a major role in the rapid spread of the Protestant Reformation under leaders such as Martin Luther (1483-1546) and John Calvin (1509-1564). Wars of religion broke out, culminating in the Thirty Years War which ravaged central Europe between 1618 and 1648. The 18th century saw the beginning of secularisation in Europe, gaining momentum after the French Revolution of 1789 and following. By the late 20th century religion had declined in most of Europe.[18]

In the 20th century, the regimes of Communist Eastern Europe and of Communist China were anti-religious. A great variety of new religious movements originated in the 20th century, many proposing syncretism of elements of established religions. Adherence to such new movements is limited, however, remaining below 2% worldwide in the period 2000-2009. Adherents of the classical world religions account for more than 75% of the world's population, while adherence to indigenous tribal religions has fallen to 4%. As of 2005[update], an estimated 14% of the world's population identifies as nonreligious.[citation needed]

By 2001 people began to use the internet to discover or adhere to their religious beliefs. In January 2000 the website beliefnet was established, and the following year, every month it had over 1.7 million visitors.[19]

See also[edit]

- Historiography of religion

- Religion and politics

- Christianity and politics

- Women as theological figures

- List of founders of religious traditions

- List of religious movements that began in the United States

Shamanism and ancestor worship[edit]

Panentheism[edit]

Polytheism[edit]

- Ancient Near Eastern religion, Egyptian mythology

- Ancient Greek religion, Ancient Roman religion

- Germanic paganism, Finnish Paganism, Norse paganism

- Maya religion, Inca religion, Aztec religion

- Neopaganism, Polytheistic reconstructionism

Monotheism[edit]

- See also Monotheism, Abrahamic religions.

Monism[edit]

Dualism[edit]

New religious movements[edit]

- History of Ayyavazhi

- Rastafari movement

- History of Wicca

- Timeline of Scientology

- Mormonism

- Bahá'í Faith

- Bábism

- History of Spiritism

- Thelema

- Ahmadiyya

Citations[edit]

- ^ "The Origins of Writing | Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

- ^ Humayun Ansari (2004). The Infidel Within: Muslims in Britain Since 1800. C. Hurst & Co. pp. 399–400. ISBN 978-1-85065-685-2.

- ^ Nongbri, Brent (2013). Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept. Yale University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0300154160.

Although the Greeks, Romans, Mesopotamians, and many other peoples have long histories, the stories of their respective religions are of recent pedigree. The formation of ancient religions as objects of study coincided with the formation of religion itself as a concept of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

- ^ Harrison, Peter (1990). 'Religion' and the Religions in the English Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0521892933.

That there exist in the world such entities as 'the religions' is an uncontroversial claim...However, it was not always so. The concepts 'religion' and 'the religions', as we presently understand them, emerged quite late in Western thought, during the Enlightenment. Between them, these two notions provided a new framework for classifying particular aspects of human life.

- ^ Nongbri, Brent (2013). "2. Lost in Translation: Inserting "Religion" into Ancient Texts". Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300154160.

- ^ Morreall, John; Sonn, Tamara (2013). 50 Great Myths about Religions. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 13. ISBN 9780470673508.

Many languages do not even have a word equivalent to our word 'religion'; nor is such a word found in either the Bible or the Qur'an.

- ^ Daniel Dubuisson. The Western Construction of Religion. 1998. William Sayers (trans.) Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. p. 90.

- ^ Timothy Fitzgerald. Discourse on Civility and Barbarity. ISBN 9780190293642. Oxford University Press, 2007. pp.45-46.

- ^ "Religion". Encyclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europeo-Americana, 70 vols. Madrid. 1907-1930.

- ^ "The World's First Temple". Archaeology magazine. Nov–Dec 2008. p. 23.

- ^ Sagona, Claudia. The Archaeology of Malta. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9781107006690. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ Budge, Wallis. An Introduction to Ancient Egyptian Literature. p. 9. ISBN 0-486-29502-8.

- ^ Allen, James. The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. ISBN 1-58983-182-9.

- ^ Shermer, Michael. The Science of Good and Evil. ISBN 0-8050-7520-8.

- ^ Compare: Diamond, Jared. "chapter 14, From Egalitarianism to Kleptocracy". Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. ISBN 9780393609295.

[...] extensive long-term information about band and tribal societies reveals that murder is a leading cause of death.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 30.

- ^ Zimmer 1953, p. 182-183.

- ^ Norris, Pippa (2011). Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Zabriskie, Phil (2001-06-04). "I Once Was Lost, but Now I'm Wired". 157 (22). Time Asia.

Sources[edit]

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Campbell, Joseph, ed., Philosophies Of India, London, E.C. 4: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6

Further reading[edit]

- Armstrong, Karen. A History of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam (1994) excerpt and text search

- Armstrong, Karen. Islam: A Short History (2002) excerpt and text search

- Bowker, John Westerdale, ed. The Oxford Dictionary of World Religions (2007) excerpt and text search 1126pp

- Carus, Paul. The history of the devil and the idea of evil: from the earliest times to the present day (1899) full text

- Eliade, Mircea, and Joan P. Culianu. The HarperCollins Concise Guide to World Religion: The A-to-Z Encyclopedia of All the Major Religious Traditions (1999) covers 33 principal religions, including Buddhism, Christianity, Jainism, Judaism, Islam, Shinto, Shamanism, Taoism, South American religions, Baltic and Slavic religions, Confucianism, and the religions of Africa and Oceania.

- Eliade, Mircea ed. Encyclopedia of Religion (16 vol. 1986; 2nd ed 15 vol. 2005; online at Gale Virtual Reference Library). 3300 articles in 15,000 pages by 2000 experts.

- Ellwood, Robert S. and Gregory D. Alles. The Encyclopedia of World Religions (2007) 528pp; for middle schools

- Gilley, Sheridan; Shiels, W. J. History of Religion in Britain: Practice and Belief from Pre-Roman Times to the Present (1994) 590pp

- James, Paul; Mandaville, Peter (2010). Globalization and Culture, Vol. 2: Globalizing Religions. London: Sage Publications.

- Marshall, Peter. "(Re)defining the English Reformation," Journal of British Studies, July 2009, Vol. 48#3 pp 564–586

- Schultz, Kevin M.; Harvey, Paul. "Everywhere and Nowhere: Recent Trends in American Religious History and Historiography," Journal of the American Academy of Religion, March 2010, Vol. 78#1 pp 129–162

- Wilson, John F. Religion and the American Nation: Historiography and History (2003) 119pp