Afterlife

The afterlife (also referred to as life after death) is the belief that the essential part of an individual's identity or the stream of consciousness continues after the death of the physical body. According to various ideas about the afterlife, the essential aspect of the individual that lives on after death may be some partial element, or the entire soul or spirit, of an individual, which carries with it and may confer personal identity or, on the contrary, may not, as in Indian nirvana. Belief in an afterlife is in contrast to the belief in oblivion after death.

In some views, this continued existence often takes place in a spiritual realm, and in other popular views, the individual may be reborn into this world and begin the life cycle over again, likely with no memory of what they have done in the past. In this latter view, such rebirths and deaths may take place over and over again continuously until the individual gains entry to a spiritual realm or Otherworld. Major views on the afterlife derive from religion, esotericism and metaphysics.

Some belief systems, such as those in the Abrahamic tradition, hold that the dead go to a specific plane of existence after death, as determined by God, or other divine judgment, based on their actions or beliefs during life. In contrast, in systems of reincarnation, such as those in the Indian religions, the nature of the continued existence is determined directly by the actions of the individual in the ended life, rather than through the decision of a different being.

Different metaphysical models[edit]

Theists generally believe some type of afterlife awaits people when they die. Members of some generally non-theistic religions tend to believe in an afterlife, but without reference to a deity. The Sadducees were an ancient Jewish sect that generally believed that there was a God but no afterlife.

Many religions, whether they believe in the soul's existence in another world like Christianity, Islam and many pagan belief systems, or in reincarnation like many forms of Hinduism and Buddhism, believe that one's status in the afterlife is a reward or punishment for their conduct during life.

Reincarnation[edit]

Reincarnation is the philosophical or religious concept that an aspect of a living being starts a new life in a different physical body or form after each biological death. It is also called rebirth or transmigration, and is a part of the Saṃsāra doctrine of cyclic existence.[1][2] It is a central tenet of all major Indian religions, namely Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Sikhism.[3][4][5] The idea of reincarnation is found in many ancient cultures,[6] and a belief in rebirth/metempsychosis was held by Greek historic figures, such as Pythagoras, Socrates, and Plato.[7] It is also a common belief of various ancient and modern religions such as Spiritism, Theosophy, and Eckankar and is found as well in many tribal societies around the world, in places such as Australia, East Asia, Siberia, and South America.[8]

Although the majority of denominations within the Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam do not believe that individuals reincarnate, particular groups within these religions do refer to reincarnation; these groups include the mainstream historical and contemporary followers of Kabbalah, the Cathars, Alawites, the Druze,[9] and the Rosicrucians.[10] The historical relations between these sects and the beliefs about reincarnation that were characteristic of Neoplatonism, Orphism, Hermeticism, Manicheanism, and Gnosticism of the Roman era as well as the Indian religions have been the subject of recent scholarly research.[11] Unity Church and its founder Charles Fillmore teach reincarnation.

Rosicrucians[12] speak of a life review period occurring immediately after death and before entering the afterlife's planes of existence (before the silver cord is broken), followed by a judgment, more akin to a final review or end report over one's life.[13]

Heaven and hell[edit]

Heaven, the heavens, seven heavens, pure lands, Tian, Jannah, Valhalla, or the Summerland, is a common religious, cosmological, or transcendent place where beings such as gods, angels, jinn, saints, or venerated ancestors are said to originate, be enthroned, or live. According to the beliefs of some religions, heavenly beings can descend to earth or incarnate, and earthly beings can ascend to heaven in the afterlife, or in exceptional cases enter heaven alive.

Heaven is often described as a "higher place", the holiest place, a paradise, in contrast to hell or the underworld or the "low places", and universally or conditionally accessible by earthly beings according to various standards of divinity, goodness, piety, faith or other virtues or right beliefs or simply the will of God. Some believe in the possibility of a heaven on Earth in a world to come.

In Indian religions, heaven is considered as Svarga loka. There are seven positive regions the soul can go to after death and seven negative regions.[14] After completing its stay in the respective region, the soul is subjected to rebirth in different living forms according to its karma. This cycle can be broken after a soul achieves Moksha or Nirvana. Any place of existence, either of humans, souls or deities, outside the tangible world (heaven, hell, or other) is referred to as otherworld.

Hell, in many religious and folkloric traditions, is a place of torment and punishment in the afterlife. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hell as an eternal destination, while religions with a cyclic history often depict a hell as an intermediary period between incarnations. Typically, these traditions locate hell in another dimension or under the earth's surface and often include entrances to hell from the land of the living. Other afterlife destinations include purgatory and limbo.

Traditions that do not conceive of the afterlife as a place of punishment or reward merely describe hell as an abode of the dead, the grave, a neutral place (for example, sheol or Hades) located under the surface of earth.

Ancient religions[edit]

Ancient Egyptian religion[edit]

The afterlife played an important role in Ancient Egyptian religion, and its belief system is one of the earliest known in recorded history. When the body died, parts of its soul known as ka (body double) and the ba (personality) would go to the Kingdom of the Dead. While the soul dwelt in the Fields of Aaru, Osiris demanded work as restitution for the protection he provided. Statues were placed in the tombs to serve as substitutes for the deceased.[15]

Arriving at one's reward in afterlife was a demanding ordeal, requiring a sin-free heart and the ability to recite the spells, passwords and formulae of the Book of the Dead. In the Hall of Two Truths, the deceased's heart was weighed against the Shu feather of truth and justice taken from the headdress of the goddess Ma'at.[16] If the heart was lighter than the feather, they could pass on, but if it were heavier they would be devoured by the demon Ammit.[17]

Egyptians also believed that being mummified and put in a sarcophagus (an ancient Egyptian "coffin" carved with complex symbols and designs, as well as pictures and hieroglyphs) was the only way to have an afterlife. Only if the corpse had been properly embalmed and entombed in a mastaba, could the dead live again in the Fields of Yalu and accompany the Sun on its daily ride. Due to the dangers the afterlife posed, the Book of the Dead was placed in the tomb with the body as well as food, jewellery, and 'curses'. They also used the "opening of the mouth".[18][19]

Ancient Egyptian civilization was based on religion; their belief in the rebirth after death became the driving force behind their funeral practices. Death was simply a temporary interruption, rather than complete cessation, of life, and that eternal life could be ensured by means like piety to the gods, preservation of the physical form through mummification, and the provision of statuary and other funerary equipment. Each human consisted of the physical body, the ka, the ba, and the akh. The Name and Shadow were also living entities. To enjoy the afterlife, all these elements had to be sustained and protected from harm.[20]

On March 30, 2010, a spokesman for the Egyptian Culture Ministry claimed it had unearthed a large red granite door in Luxor with inscriptions by User,[21] a powerful adviser to the 18th dynasty Queen Hatshepsut who ruled between 1479 BC and 1458 BC, the longest of any woman. It believes the false door is a 'door to the Afterlife'. According to the archaeologists, the door was reused in a structure in Roman Egypt.

Ancient Greek and Roman religions[edit]

The Greek god Hades is known in Greek mythology as the king of the underworld, a place where souls live after death.[22] The Greek god Hermes, the messenger of the gods, would take the dead soul of a person to the underworld (sometimes called Hades or the House of Hades). Hermes would leave the soul on the banks of the River Styx, the river between life and death.[23]

Charon, also known as the ferry-man, would take the soul across the river to Hades, if the soul had gold: Upon burial, the family of the dead soul would put coins under the deceased's tongue. Once crossed, the soul would be judged by Aeacus, Rhadamanthus and King Minos. The soul would be sent to Elysium, Tartarus, Asphodel Fields, or the Fields of Punishment. The Elysian Fields were for the ones that lived pure lives. It consisted of green fields, valleys and mountains, everyone there was peaceful and contented, and the Sun always shone there. Tartarus was for the people that blasphemed against the gods, or were simply rebellious and consciously evil.[24]

The Asphodel Fields were for a varied selection of human souls: Those whose sins equalled their goodness, were indecisive in their lives, or were not judged. The Fields of Punishment were for people that had sinned often, but not so much as to be deserving of Tartarus. In Tartarus, the soul would be punished by being burned in lava, or stretched on racks. Some heroes of Greek legend are allowed to visit the underworld. The Romans had a similar belief system about the afterlife, with Hades becoming known as Pluto. In the ancient Greek myth about the Labours of Heracles, the hero Heracles had to travel to the underworld to capture Cerberus, the three-headed guard dog, as one of his tasks.

In Dream of Scipio, Cicero describes what seems to be an out of body experience, of the soul traveling high above the Earth, looking down at the small planet, from far away.[25]

In Book VI of Virgil's Aeneid, the hero, Aeneas, travels to the underworld to see his father. By the River Styx, he sees the souls of those not given a proper burial, forced to wait by the river until someone buries them. While down there, along with the dead, he is shown the place where the wrongly convicted reside, the fields of sorrow where those who committed suicide and now regret it reside, including Aeneas' former lover, the warriors and shades, Tartarus (where the titans and powerful non-mortal enemies of the Olympians reside) where he can hear the groans of the imprisoned, the palace of Pluto, and the fields of Elysium where the descendants of the divine and bravest heroes reside. He sees the river of forgetfulness, Lethe, which the dead must drink to forget their life and begin anew. Lastly, his father shows him all of the future heroes of Rome who will live if Aeneas fulfills his destiny in founding the city.

Norse religion[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The Poetic and Prose Eddas, the oldest sources for information on the Norse concept of the afterlife, vary in their description of the several realms that are described as falling under this topic. The most well-known are:

- Valhalla: (lit. "Hall of the Slain" i.e. "the Chosen Ones") Half the warriors who die in battle join the god Odin who rules over a majestic hall called Valhalla in Asgard.[26]

- Fólkvangr: (lit. "Field of the Host") The other half join the goddess Freyja in a great meadow known as Fólkvangr.[27]

- Hel: (lit. "The Covered Hall") This abode is somewhat like Hades from Ancient Greek religion: there, something not unlike the Asphodel Meadows can be found, and people who have neither excelled in that which is good nor excelled in that which is bad can expect to go there after they die and be reunited with their loved ones.[citation needed]

- Niflhel: (lit. "The Dark" or "Misty Hel") This realm is roughly analogous to Greek Tartarus. It is the deeper level beneath Hel, and those who break oaths and commit other vile things will be sent there to be among their kind to suffer harsh punishments.[citation needed]

Abrahamic religions[edit]

Bahá'í Faith[edit]

The teachings of the Bahá'í Faith state that the nature of the afterlife is beyond the understanding of those living, just as an unborn fetus cannot understand the nature of the world outside of the womb. The Bahá'í writings state that the soul is immortal and after death it will continue to progress until it attains God's presence. In Bahá'í belief, souls in the afterlife will continue to retain their individuality and consciousness and will be able to recognize and communicate spiritually with other souls whom they have made deep profound friendships with, such as their spouses.[28]

The Bahá'í scriptures also state there are distinctions between souls in the afterlife, and that souls will recognize the worth of their own deeds and understand the consequences of their actions. It is explained that those souls that have turned toward God will experience gladness, while those who have lived in error will become aware of the opportunities they have lost. Also, in the Baha'i view, souls will be able to recognize the accomplishments of the souls that have reached the same level as themselves, but not those that have achieved a rank higher than them.[28]

Christianity[edit]

This section relies too much on references to primary sources. (July 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Mainstream Christianity professes belief in the Nicene Creed, and English versions of the Nicene Creed in current use include the phrase: "We look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come." Although punishments are made part of certain Christian conceptions of the afterlife, the prevalent concept of "eternal damnation" is a tenet of the Christian afterlife.

When questioned by the Sadducees about the resurrection of the dead (in a context relating to who one's spouse would be if one had been married several times in life), Jesus said that marriage will be irrelevant after the resurrection as the resurrected will be like the angels in heaven.[29]

Jesus also maintained that the time would come when the dead would hear the voice of the Son of God, and all who were in the tombs would come out, who have done good deeds to the resurrection of life, but those who have done wicked deeds to the resurrection of condemnation.[30]

The Book of Enoch describes Sheol as divided into four compartments for four types of the dead: the faithful saints who await resurrection in Paradise, the merely virtuous who await their reward, the wicked who await punishment, and the wicked who have already been punished and will not be resurrected on Judgment Day.[31] The Book of Enoch is considered apocryphal by most denominations of Christianity and all denominations of Judaism.

The book of 2 Maccabees gives a clear account of the dead awaiting a future resurrection and judgment, plus prayers and offerings for the dead to remove the burden of sin.

The author of Luke recounts the story of Lazarus and the rich man, which shows people in Hades awaiting the resurrection either in comfort or torment. The author of the Book of Revelation writes about God and the angels versus Satan and demons in an epic battle at the end of times when all souls are judged. There is mention of ghostly bodies of past prophets, and the transfiguration.

The non-canonical Acts of Paul and Thecla speak of the efficacy of prayer for the dead, so that they might be "translated to a state of happiness".[32]

Hippolytus of Rome pictures the underworld (Hades) as a place where the righteous dead, awaiting in the bosom of Abraham their resurrection, rejoice at their future prospect, while the unrighteous are tormented at the sight of the "lake of unquenchable fire" into which they are destined to be cast.

Gregory of Nyssa discusses the long-before believed possibility of purification of souls after death.[33]

Pope Gregory I repeats the concept, articulated over a century earlier by Gregory of Nyssa that the saved suffer purification after death, in connection with which he wrote of "purgatorial flames".

The noun "purgatorium" (Latin: place of cleansing[34]) is used for the first time to describe a state of painful purification of the saved after life. The same word in adjectival form (purgatorius -a -um, cleansing), which appears also in non-religious writing,[35] was already used by Christians such as Augustine of Hippo and Pope Gregory I to refer to an after-death cleansing.

During the Age of Enlightenment, theologians and philosophers presented various philosophies and beliefs. A notable example is Emanuel Swedenborg who wrote some 18 theological works which describe in detail the nature of the afterlife according to his claimed spiritual experiences, the most famous of which is Heaven and Hell.[36] His report of life there covers a wide range of topics, such as marriage in heaven (where all angels are married), children in heaven (where they are raised by angel parents), time and space in heaven (there are none), the after-death awakening process in the World of Spirits (a place halfway between Heaven and Hell and where people first wake up after death), the allowance of a free will choice between Heaven or Hell (as opposed to being sent to either one by God), the eternity of Hell (one could leave but would never want to), and that all angels or devils were once people on earth.[36]

The Catholic Church[edit]

The "Spiritual Combat", a written work by Lorenzo Scupoli, states that four assaults are attempted by the "evil one" at the hour of death.[37] The Catholic conception of the afterlife teaches that after the body dies, the soul is judged, the righteous and free of sin enter Heaven. However, those who die in unrepented mortal sin go to hell. In the 1990s, the Catechism of the Catholic Church defined hell not as punishment imposed on the sinner but rather as the sinner's self-exclusion from God. Unlike other Christian groups, the Catholic Church teaches that those who die in a state of grace, but still carry venial sin go to a place called Purgatory where they undergo purification to enter Heaven.

Limbo[edit]

Despite popular opinion, Limbo, which was elaborated upon by theologians beginning in the Middle Ages, was never recognized as a dogma of the Catholic Church, yet, at times, it has been a very popular theological theory within the Church. Limbo is a theory that unbaptized but innocent souls, such as those of infants, virtuous individuals who lived before Jesus Christ was born on earth, or those that die before baptism exist in neither Heaven or Hell proper. Therefore, these souls neither merit the beatific vision, nor are subjected to any punishment, because they are not guilty of any personal sin although they have not received baptism, so still bear original sin. So they are generally seen as existing in a state of natural, but not supernatural, happiness, until the end of time.

In other Christian denominations it has been described as an intermediate place or state of confinement in oblivion and neglect.[38]

Purgatory[edit]

The notion of purgatory is associated particularly with the Catholic Church. In the Catholic Church, all those who die in God's grace and friendship, but still imperfectly purified, are indeed assured of their eternal salvation; but after death they undergo purification, so as to achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of heaven or the final purification of the elect, which is entirely different from the punishment of the damned. The tradition of the church, by reference to certain texts of scripture, speaks of a "cleansing fire" although it is not always called purgatory.

Anglicans of the Anglo-Catholic tradition generally also hold to the belief. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, believed in an intermediate state between death and the resurrection of the dead and in the possibility of "continuing to grow in holiness there", but Methodism does not officially affirm this belief and denies the possibility of helping by prayer any who may be in that state.[39]

Orthodox Christianity[edit]

The Orthodox Church is intentionally reticent on the afterlife, as it acknowledges the mystery especially of things that have not yet occurred. Beyond the second coming of Jesus, bodily resurrection, and final judgment, all of which is affirmed in the Nicene Creed (325 CE), Orthodoxy does not teach much else in any definitive manner. Unlike Western forms of Christianity, however, Orthodoxy is traditionally non-dualist and does not teach that there are two separate literal locations of heaven and hell, but instead acknowledges that "the 'location' of one's final destiny—heaven or hell—as being figurative."[40] Instead, Orthodoxy teaches that the final judgment is simply one's uniform encounter with divine love and mercy, but this encounter is experienced multifariously depending on the extent to which one has been transformed, partaken of divinity, and is therefore compatible or incompatible with God. "The monadic, immutable, and ceaseless object of eschatological encounter is therefore the love and mercy of God, his glory which infuses the heavenly temple, and it is the subjective human reaction which engenders multiplicity or any division of experience."[40] For instance, St. Isaac the Syrian observes that "those who are punished in Gehenna, are scourged by the scourge of love. ... The power of love works in two ways: it torments sinners ... [as] bitter regret. But love inebriates the souls of the sons of Heaven by its delectability."[41] In this sense, the divine action is always, immutably, and uniformly love and if one experiences this love negatively, the experience is then one of self-condemnation because of free will rather than condemnation by God. Orthodoxy therefore uses the description of Jesus' judgment in John 3:19–21 as their model: "19 And this is the judgment: the light has come into the world, and people loved the darkness rather than the light because their works were evil. 20 For everyone who does wicked things hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his works should be exposed. 21 But whoever does what is true comes to the light, so that it may be clearly seen that his works have been carried out in God." As a characteristically Orthodox understanding, then, Fr. Thomas Hopko writes, "[I]t is precisely the presence of God's mercy and love which cause the torment of the wicked. God does not punish; he forgives... . In a word, God has mercy on all, whether all like it or not. If we like it, it is paradise; if we do not, it is hell. Every knee will bend before the Lord. Everything will be subject to Him. God in Christ will indeed be "all and in all," with boundless mercy and unconditional pardon. But not all will rejoice in God's gift of forgiveness, and that choice will be judgment, the self-inflicted source of their sorrow and pain."[42]

Moreover, Orthodoxy includes a prevalent tradition of apokatastasis, or the restoration of all things in the end. This has been taught most notably by Origen, but also many other Church fathers and Saints, including Gregory of Nyssa. The Second Council of Constantinople (553 CE) affirmed the orthodoxy of Gregory of Nyssa while simultaneously condemning Origen's brand of universalism because it taught the restoration back to our pre-existent state, which Orthodoxy doesn't teach. It is also a teaching of such eminent Orthodox theologians as Olivier Clément, Metropolitan Kallistos Ware, and Bishop Hilarion Alfeyev.[43] Although apokatastasis is not a dogma of the church but instead a theologoumena, it is no less a teaching of the Orthodox Church than its rejection. As Met. Kallistos Ware explains, "It is heretical to say that all must be saved, for this is to deny free will; but, it is legitimate to hope that all may be saved,"[44] as insisting on torment without end also denies free will.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints[edit]

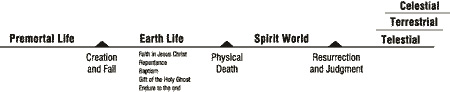

Joseph F. Smith of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints presents an elaborate vision of the afterlife. It is revealed as the scene of an extensive missionary effort by righteous spirits in paradise to redeem those still in darkness—a spirit prison or "hell" where the spirits of the dead remain until judgment. It is divided into two parts: Spirit Prison and Paradise. Together these are also known as the Spirit World (also Abraham's Bosom; see Luke 16:19–25). They believe that Christ visited spirit prison (1 Peter 3:18–20) and opened the gate for those who repent to cross over to Paradise. This is similar to the Harrowing of Hell doctrine of some mainstream Christian faiths.[citation needed] Both Spirit Prison and Paradise are temporary according to Latter-day Saint beliefs. After the resurrection, spirits are assigned "permanently" to three degrees of heavenly glory, determined by how they lived – Celestial, Terrestrial, and Telestial. (1 Cor 15:44–42; Doctrine and Covenants, Section 76) Sons of Perdition, or those who have known and seen God and deny it, will be sent to the realm of Satan, which is called Outer Darkness, where they shall live in misery and agony forever.[45]

The Celestial Kingdom is believed to be a place where we can live eternally with our families. Progression does not end once one has entered the Celestial Kingdom, but it extends eternally. According to "True to the Faith" (a handbook on doctrines in the LDS faith), "The celestial kingdom is the place prepared for those who have "received the testimony of Jesus" and been "made perfect through Jesus the mediator of the new covenant, who wrought out this perfect atonement through the shedding of his own blood" (D&C 76:51, 69). To inherit this gift, we must receive the ordinances of salvation, keep the commandments, and repent of our sins."[46]

Jehovah's Witnesses[edit]

Jehovah's Witnesses occasionally use terms such as "afterlife"[47] to refer to any hope for the dead, but they understand Ecclesiastes 9:5 to preclude belief in an immortal soul.[48] Individuals judged by God to be wicked, such as in the Great Flood or at Armageddon, are given no hope of an afterlife. However, they believe that after Armageddon there will be a bodily resurrection of "both righteous and unrighteous" dead (but not the "wicked"). Survivors of Armageddon and those who are resurrected are then to gradually restore earth to a paradise.[49] After Armageddon, unrepentant sinners are punished with eternal death (non-existence).

Seventh-day Adventists[edit]

The Seventh-day Adventist Church, teaches that the first death, or death brought about by living on a planet with sinful conditions (sickness, old age, accident, etc.) is a sleep of the soul. Adventists believe that the body + the breath of God = a living soul. Like Jehovah's Witnesses, Adventists use key phrases from the Bible, such as "For the living know that they shall die: but the dead know not any thing, neither have they any more a reward; for the memory of them is forgotten." (Eccl. 9:5 KJV). Adventists also point to the fact that the wage of sin is death and God alone is immortal. Adventists believe God will grant eternal life to the redeemed who are resurrected at Jesus' second coming. Until then, all those who have died are "asleep". When Jesus the Christ, who is the Word and the Bread of Life, comes a second time, the righteous will be raised incorruptible and will be taken in the clouds to meet their Lord. The righteous will live in heaven for a thousand years (the millennium) where they will sit with God in judgment over the unredeemed and the fallen angels. During the time the redeemed are in heaven, the Earth will be devoid of human and animal inhabitation. Only the fallen angels will be left alive. The second resurrection is of the unrighteous, when Jesus brings the New Jerusalem down from heaven to relocate to Earth. Jesus will call to life all those who are unrighteous. Satan and his angels will convince the unrighteous to surround the city, but hell fire and brimstone will fall from heaven and consume them, thus cleansing Earth of all sin. The universe will be then free from sin forever. This is called the second death. On the new earth God will provide an eternal home for all the redeemed and a perfect environment for everlasting life, where Eden will be restored. The great controversy will be ended and sin will be no more. God will reign in perfect harmony forever. (Rom. 6:23; 1 Tim. 6:15, 16; Eccl. 9:5, 6; Ps. 146:3, 4; John 11:11–14; Col. 3:4; 1 Cor. 15:51–54; 1 Thess. 4:13–17; John 5:28, 29; Rev. 20:1–10; Rev. 20; 1 Cor. 6:2, 3; Jer. 4:23–26; Rev. 21:1–5; Mal. 4:1; Eze. 28:18, 19; 2 Peter 3:13; Isa. 35; 65:17–25; Matt. 5:5; Rev. 21:1–7; 22:1–5; 11:15.)[50][51]

Islam[edit]

The Islamic belief in the afterlife as stated in the Quran is descriptive. The Arabic word for Paradise is Jannah and Hell is Jahannam. Their level of comfort while in the grave (according to some commentators) depends wholly on their level of iman or faith in the one almighty creator or supreme being (God or Allah). In order for one to achieve proper, firm and healthy iman one must practice righteous deeds or else his level of iman chokes and shrinks and eventually can wither away if one does not practice Islam long enough, hence the depth of practicing Islam is good deeds. One may also acquire tasbih and recite the names of Allah in such manner as Subahann Allah or "Glory be to Allah" over and over again to acquire good deeds.

In the Quran, God gives warning about grievous punishment to those who do not believe in the afterlife (Akhirah),[52] and admonishes mankind that Hell is prepared for those who deny the meeting with him.[53]

Islam teaches that the purpose of Man's entire creation is to worship Allah alone, which includes being kind to other human beings and life including bugs, and to trees, by not oppressing them. Islam teaches that the life we live on Earth is nothing but a test for us and to determine each individual's ultimate abode, be it punishment or Jannat in the afterlife, which is eternal and everlasting.

Jannah and Jahannam both have different levels. Jannah has eight gates and seven levels. The higher the level the better it is and the happier you are. Jahannam possess 7 deep terrible layers. The lower the layer the worse it is. Individuals will arrive at both everlasting homes during Judgment Day, which commences after the Angel Israfil blows the trumpet the second time. Islam teaches the continued existence of the soul and a transformed physical existence after death. Muslims believe there will be a day of judgment when all humans will be divided between the eternal destinations of Paradise and Hell.

In the 20th century, discussions about the afterlife address the interconnection between human action and divine judgment, the need for moral rectitude, and the eternal consequences of human action in this life and world.[54]

A central doctrine of the Quran is the Last Day, on which the world will be destroyed and Allah will raise all people and jinn from the dead to be judged. The Last Day is also called the Day of Standing Up, Day of Separation, Day of Reckoning, Day of Awakening, Day of Judgment, The Encompassing Day or The Hour.

Until the Day of Judgment, deceased souls remain in their graves awaiting the resurrection. However, they begin to feel immediately a taste of their destiny to come. Those bound for hell will suffer in their graves, while those bound for heaven will be in peace until that time.

The resurrection that will take place on the Last Day is physical, and is explained by suggesting that God will re-create the decayed body (17:100: "Could they not see that God who created the heavens and the earth is able to create the like of them?").

On the Last Day, resurrected humans and jinn will be judged by Allah according to their deeds. One's eternal destination depends on balance of good to bad deeds in life. They are either granted admission to Paradise, where they will enjoy spiritual and physical pleasures forever, or condemned to Hell to suffer spiritual and physical torment for eternity. The day of judgment is described as passing over Hell on a narrow bridge (as thin as human hair and sharper than a razor) in order to enter Paradise. Those who fall, weighted by their bad deeds, will remain in Hell forever.

Ahmadiyya[edit]

Ahmadi believe that the afterlife is not material but of a spiritual nature. According to Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the founder of Ahmadiyya religion, the soul will give birth to another rarer entity and will resemble the life on this earth in the sense that this entity will bear a similar relationship to the soul as the soul bears relationship with the human existence on earth. On earth, if a person leads a righteous life and submits to the will of God, his or her tastes become attuned to enjoying spiritual pleasures as opposed to carnal desires. With this, an "embryonic soul" begins to take shape. Different tastes are said to be born which a person given to carnal passions finds no enjoyment. For example, sacrifice of one's own rights over that of others becomes enjoyable, or that forgiveness becomes second nature. In such a state a person finds contentment and peace at heart and at this stage, according to Ahmadiyya beliefs, it can be said that a soul within the soul has begun to take shape.[55]

Sufi[edit]

The Sufi scholar Ibn 'Arabi defined Barzakh as the intermediate realm or "isthmus." It is between the world of corporeal bodies and the world of spirits, and is a means of contact between the two worlds. Without it, there would be no contact between the two and both would cease to exist. He described it as simple and luminous, like the world of spirits, but also able to take on many different forms just like the world of corporeal bodies can. In broader terms Barzakh, "is anything that separates two things". It has been called the dream world in which the dreamer is in both life and death.[56]

Judaism[edit]

She'ol[edit]

She'ol, in the Hebrew Bible, is a place of darkness to which all the dead go, both the righteous and the unrighteous, regardless of the moral choices made in life, a place of stillness and darkness cut off from life and from God.[57][need quotation to verify]

The inhabitants of Sheol are the "shades" (rephaim), entities without personality or strength.[58] Under some circumstances they are thought to be able to be contacted by the living, as the Witch of Endor contacts the shade of Samuel for Saul, but such practices are forbidden (Deuteronomy 18:10).[59]

While the Hebrew Bible appears to describe Sheol as the permanent place of the dead, in the Second Temple period (roughly 500 BC – 70 AD) a more diverse set of ideas developed. In some texts, Sheol is considered to be the home of both the righteous and the wicked, separated into respective compartments; in others, it was considered a place of punishment, meant for the wicked dead alone.[60] When the Hebrew scriptures were translated into Greek in ancient Alexandria around 200 BC, the word "Hades" (the Greek underworld) was substituted for Sheol. This is reflected in the New Testament where Hades is both the underworld of the dead and the personification of the evil it represents.[60]

World to Come[edit]

The Talmud offers a number of thoughts relating to the afterlife. After death, the soul is brought for judgment. Those who have led pristine lives enter immediately into the Olam Haba or world to come. Most do not enter the world to come immediately, but now experience a period of review of their earthly actions and they are made aware of what they have done wrong. Some view this period as being a "re-schooling", with the soul gaining wisdom as one's errors are reviewed. Others view this period to include spiritual discomfort for past wrongs. At the end of this period, not longer than one year, the soul then takes its place in the world to come. Although discomforts are made part of certain Jewish conceptions of the afterlife, the concept of "eternal damnation", so prevalent in other religions, is not a tenet of the Jewish afterlife. According to the Talmud, extinction of the soul is reserved for a far smaller group of malicious and evil leaders, either whose very evil deeds go way beyond norms, or who lead large groups of people to utmost evil.[61][62]

Maimonides describes the Olam Haba in spiritual terms, relegating the prophesied physical resurrection to the status of a future miracle, unrelated to the afterlife or the Messianic era. According to Maimonides, an afterlife continues for the soul of every human being, a soul now separated from the body in which it was "housed" during its earthly existence.

The Zohar describes Gehenna not as a place of punishment for the wicked but as a place of spiritual purification for souls.[63]

Reincarnation in Jewish tradition[edit]

Although there is no reference to reincarnation in the Talmud or any prior writings,[64] according to rabbis such as Avraham Arieh Trugman, reincarnation is recognized as being part and parcel of Jewish tradition. Trugman explains that it is through oral tradition that the meanings of the Torah, its commandments and stories, are known and understood. The classic work of Jewish mysticism,[65] the Zohar, is quoted liberally in all Jewish learning; in the Zohar the idea of reincarnation is mentioned repeatedly. Trugman states that in the last five centuries the concept of reincarnation, which until then had been a much hidden tradition within Judaism, was given open exposure.[65]

Shraga Simmons commented that within the Bible itself, the idea [of reincarnation] is intimated in Deut. 25:5–10, Deut. 33:6 and Isaiah 22:14, 65:6.[66]

Yirmiyahu Ullman wrote that reincarnation is an "ancient, mainstream belief in Judaism". The Zohar makes frequent and lengthy references to reincarnation. Onkelos, a righteous convert and authoritative commentator of the same period, explained the verse, "Let Reuben live and not die ..." (Deuteronomy 33:6) to mean that Reuben should merit the World to Come directly, and not have to die again as a result of being reincarnated. Torah scholar, commentator and kabbalist, Nachmanides (Ramban 1195–1270), attributed Job's suffering to reincarnation, as hinted in Job's saying "God does all these things twice or three times with a man, to bring back his soul from the pit to ... the light of the living' (Job 33:29, 30)."[67]

Reincarnation, called gilgul, became popular in folk belief, and is found in much Yiddish literature among Ashkenazi Jews. Among a few kabbalists, it was posited that some human souls could end up being reincarnated into non-human bodies. These ideas were found in a number of Kabbalistic works from the 13th century, and also among many mystics in the late 16th century. Martin Buber's early collection of stories of the Baal Shem Tov's life includes several that refer to people reincarnating in successive lives.[68]

Among well known (generally non-kabbalist or anti-kabbalist) rabbis who rejected the idea of reincarnation are Saadia Gaon, David Kimhi, Hasdai Crescas, Yedayah Bedershi (early 14th century), Joseph Albo, Abraham ibn Daud, the Rosh and Leon de Modena. Saadia Gaon, in Emunoth ve-Deoth (Hebrew: "beliefs and opinions") concludes Section VI with a refutation of the doctrine of metempsychosis (reincarnation). While rebutting reincarnation, Saadia Gaon further states that Jews who hold to reincarnation have adopted non-Jewish beliefs. By no means do all Jews today believe in reincarnation, but belief in reincarnation is not uncommon among many Jews, including Orthodox.

Other well-known rabbis who are reincarnationists include Yonassan Gershom, Abraham Isaac Kook, Talmud scholar Adin Steinsaltz, DovBer Pinson, David M. Wexelman, Zalman Schachter,[69] and many others. Reincarnation is cited by authoritative biblical commentators, including Ramban (Nachmanides), Menachem Recanti and Rabbenu Bachya.

Among the many volumes of Yitzchak Luria, most of which come down from the pen of his primary disciple, Chaim Vital, are insights explaining issues related to reincarnation. His Shaar HaGilgulim, "The Gates of Reincarnation", is a book devoted exclusively to the subject of reincarnation in Judaism.

Rabbi Naftali Silberberg of The Rohr Jewish Learning Institute notes that "Many ideas that originate in other religions and belief systems have been popularized in the media and are taken for granted by unassuming Jews."[70]

South Asian religions[edit]

Buddhism[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Buddhists maintain that rebirth takes place without an unchanging self or soul passing from one form to another.[71] The type of rebirth will be conditioned by the moral tone of the person's actions (kamma or karma). For example, if a person has committed harmful actions of body, speech and mind based on greed, hatred and delusion, rebirth in a lower realm, i.e. an animal, a hungry ghost or a hell realm, is to be expected. On the other hand, where a person has performed skillful actions based on generosity, loving-kindness (metta), compassion and wisdom, rebirth in a happy realm, i.e. human or one of the many heavenly realms, can be expected.

Yet the mechanism of rebirth with kamma is not deterministic. It depends on various levels of kamma. The most important moment that determines where a person is reborn into is the last thought moment. At that moment, heavy kamma would ripen if there were performed, if not then near death kamma, if not then habitual kamma, finally if none of the above happened, then residual kamma from previous actions can ripen. According to Theravada Buddhism, there are 31 realms of existence that one can be reborn into.

Pure Land Buddhism of Mahayana believes in a special place apart from the 31 planes of existence called Pure Land. It is believed that each Buddha has their own pure land, created out of their merits for the sake of sentient beings who recall them mindfully to be able to be reborn in their pure land and train to become a Buddha there. Thus the main practice of pure land Buddhism is to chant a Buddha's name.

In Tibetan Buddhism the Tibetan Book of the Dead explains the intermediate state of humans between death and reincarnation. The deceased will find the bright light of wisdom, which shows a straightforward path to move upward and leave the cycle of reincarnation. There are various reasons why the deceased do not follow that light. Some had no briefing about the intermediate state in the former life. Others only used to follow their basic instincts like animals. And some have fear, which results from foul deeds in the former life or from insistent haughtiness. In the intermediate state the awareness is very flexible, so it is important to be virtuous, adopt a positive attitude, and avoid negative ideas. Ideas which are rising from subconsciousness can cause extreme tempers and cowing visions. In this situation they have to understand, that these manifestations are just reflections of the inner thoughts. No one can really hurt them, because they have no more material body. The deceased get help from different Buddhas who show them the path to the bright light. The ones who do not follow the path after all will get hints for a better reincarnation. They have to release the things and beings on which or whom they still hang from the life before. It is recommended to choose a family where the parents trust in the Dharma and to reincarnate with the will to care for the welfare of all beings.

"Life is cosmic energy of the universe and after death it merges in universe again and as the time comes to find the suitable place for the entity died in the life condition it gets born. There are 10 life states of any life: Hell, hunger, anger, animality, rapture, humanity, learning, realization, bodhisatva and buddhahood. The life dies in which life condition it reborn in the same life condition."[This quote needs a citation]

Hinduism[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (November 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The Upanishads describe reincarnation (punarjanma) (see also: samsara). The Bhagavad Gita, an important Hindu script, talks extensively about the afterlife. Here, Krishna says that just as a man discards his old clothes and wears new ones; similarly the soul discards the old body and takes on a new one. In Hinduism, the belief is that the body is nothing but a shell, the soul inside is immutable and indestructible and takes on different lives in a cycle of birth and death. The end of this cycle is called mukti (Sanskrit: मुक्ति) and staying finally with supreme God forever; is moksha (Sanskrit: मोक्ष) or salvation.

The Garuda Purana deals solely with what happens to a person after death. The God of Death Yama sends his representatives to collect the soul from a person's body whenever he is due for death and they take the soul to Yama. A record of each person's timings & deeds performed by him is kept in a ledger by Yama's assistant, Chitragupta.

According to the Garuda Purana, a soul after leaving the body travels through a very long and dark tunnel towards the South. This is why an oil lamp is lit and kept beside the head of the corpse, to light the dark tunnel and allow the soul to travel comfortably.

The soul, called atman leaves the body and reincarnates itself according to the deeds or karma performed by one in last birth. Rebirth would be in form of animals or other lower creatures if one performed bad karmas and in human form in a good family with joyous lifetime if the person was good in last birth. In between the two births a human is also required to either face punishments for bad karmas in "naraka" or hell or enjoy for the good karmas in swarga or heaven for good deeds. Whenever his or her punishments or rewards are over he or she is sent back to earth, also known as Mrutyulok or human world. A person stays with the God or ultimate power when he discharges only & only yajna karma (means work done for satisfaction of supreme lord only) in last birth and the same is called as moksha or nirvana, which is the ultimate goal of a self realised soul. Atma moves with Parmatma or the greatest soul. According to Bhagavad Gita an Atma or soul never dies, what dies is the body only made of five elements—Earth, Water, Fire, Air, and Sky. Soul is believed to be indestructible. None of the five elements can harm or influence it. Hinduism through Garuda Purana also describes in detail various types of narkas or Hells where a person after death is punished for his bad karmas and dealt with accordingly.

Hindus also believe in karma. Karma is the accumulated sums of one's good or bad deeds. Satkarma means good deeds, vikarma means bad deeds. According to Hinduism the basic concept of karma is 'As you sow, you shall reap'. So, if a person has lived a good life, they will be rewarded in the afterlife. Similarly their sum of bad deeds will be mirrored in their next life. Good karma brings good rewards and bad karmas lead to bad results. There is no judgment here. People accumulate karma through their actions and even thoughts. In Bhagavad Gita when Arjuna hesitates to kill his kith and kin the lord reprimands him saying thus "Do you believe that you are the doer of the action. No. You are merely an instrument in MY hands. Do you believe that the people in front of you are living? Dear Arjuna, they are already dead. As a kshatriya (warrior) it is your duty to protect your people and land. If you fail to do your duty, then you are not adhering to dharmic principles."[This quote needs a citation]

Jainism[edit]

Jainism also believes in the after life. They believe that the soul takes on a body form based on previous karmas or actions performed by that soul through eternity. Jains believe the soul is eternal and that the freedom from the cycle of reincarnation is the means to attain eternal bliss.[72]

Sikhism[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Sikhism may have a belief in the afterlife. They believe that the soul belongs to the spiritual universe which has its origins in God. However it's been a matter of great debate amongst the Sikhs about Sikhism's belief in afterlife. Many believe that Sikhism endorses the afterlife and the concept of reward and punishment as there are verses given in Guru Granth Sahib, but a large number of Sikhs believe otherwise and treat those verses as metaphorical or poetic.

Also it has been noted by many scholars that the Guru Granth Sahib includes poetic renditions from multiple saints and religious traditions like that of Kabir, Farid and Ramananda. The essential doctrine is to experience the divine through simple living, meditation and contemplation while being alive. Sikhism also has the belief of being in union with God while living. Accounts of afterlife are considered to be aimed at the popular prevailing views of the time so as to provide a referential framework without necessarily establishing a belief in the afterlife. Thus while it is also acknowledged that living the life of a householder is above the metaphysical truth, Sikhism can be considered agnostic to the question of an afterlife. Some scholars also interpret the mention of reincarnation to be naturalistic akin to the biogeochemical cycles.[73]

But if one analyses the Sikh Scriptures carefully, one may find that on many occasions the afterlife and the existence of heaven and hell are mentioned in Guru Granth Sahib and in Dasam granth, so from that it can be concluded that Sikhism does believe in the existence of heaven and hell; however, heaven and hell are created to temporarily reward and punish, and one will then take birth again until one merges in God. According to the Sikh scriptures, the human form is the closet form to God and the best opportunity for a human being to attain salvation and merge back with God. Sikh Gurus said that nothing dies, nothing is born, everything is ever present, and it just changes forms. Like standing in front of a wardrobe, you pick up a dress and wear it and then you discard it. You wear another one. Thus, in the view of Sikhism, your soul is never born and never dies. Your soul is a part of God and hence lives forever.[74]

Others[edit]

Traditional African religions[edit]

Traditional African religions are diverse in their beliefs in an afterlife. Hunter-gatherer societies such as the Hadza have no particular belief in an afterlife, and the death of an individual is a straightforward end to their existence.[75] Ancestor cults are found throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, including cultures like the Yombe,[76] Beng,[77] Yoruba and Ewe, "[T]he belief that the dead come back into life and are reborn into their families is given concrete expression in the personal names that are given to children....What is reincarnated are some of the dominant characteristics of the ancestor and not his soul. For each soul remains distinct and each birth represents a new soul."[78] The Yoruba, Dogon and LoDagoa have eschatological ideas similar to Abrahamic religions, "but in most African societies, there is a marked absence of such clear-cut notions of heaven and hell, although there are notions of God judging the soul after death."[78] In some societies like the Mende, multiple beliefs coexist. The Mende believe that people die twice: once during the process of joining the secret society, and again during biological death after which they become ancestors. However, some Mende also believe that after people are created by God they live ten consecutive lives, each in progressively descending worlds.[79] One cross-cultural theme is that the ancestors are part of the world of the living, interacting with it regularly.[80][81][82]

Shinto[edit]

It is common for families to participate in ceremonies for children at a shrine, yet have a Buddhist funeral at the time of death. In old Japanese legends, it is often claimed that the dead go to a place called yomi (黄泉), a gloomy underground realm with a river separating the living from the dead mentioned in the legend of Izanami and Izanagi. This yomi very closely resembles the Greek Hades; however, later myths include notions of resurrection and even Elysium-like descriptions such as in the legend of Okuninushi and Susanoo. Shinto tends to hold negative views on death and corpses as a source of pollution called kegare. However, death is also viewed as a path towards apotheosis in Shintoism as can be evidenced by how legendary individuals become enshrined after death. Perhaps the most famous would be Emperor Ojin who was enshrined as Hachiman the God of War after his death.

Unitarian Universalism[edit]

Some Unitarian Universalists believe in universalism: that all souls will ultimately be saved and that there are no torments of hell.[83] Unitarian Universalists differ widely in their theology hence there is no exact same stance on the issue.[84] Although Unitarians historically believed in a literal hell, and Universalists historically believed that everyone goes to heaven, modern Unitarian Universalists can be categorized into those believing in a heaven, reincarnation and oblivion. Most Unitarian Universalists believe that heaven and hell are symbolic places of consciousness and the faith is largely focused on the worldly life rather than any possible afterlife.[85]

Spiritualism[edit]

According to Edgar Cayce, the afterlife consisted of nine realms equated with the nine planets of astrology. The first, symbolized by Saturn, was a level for the purification of the souls. The second, Mercury's realm, gives us the ability to consider problems as a whole. The third of the nine soul realms is ruled by Earth and is associated with the Earthly pleasures. The fourth realm is where we find out about love and is ruled by Venus. The fifth realm is where we meet our limitations and is ruled by Mars. The sixth realm is ruled by Neptune, and is where we begin to use our creative powers and free ourselves from the material world. The seventh realm is symbolized by Jupiter, which strengthens the soul's ability to depict situations, to analyze people and places, things, and conditions. The eighth afterlife realm is ruled by Uranus and develops psychic ability. The ninth afterlife realm is symbolized by Pluto, the astrological realm of the unconscious. This afterlife realm is a transient place where souls can choose to travel to other realms or other solar systems, it is the souls liberation into eternity, and is the realm that opens the doorway from our solar system into the cosmos.[86]

Mainstream Spiritualists postulate a series of seven realms that are not unlike Edgar Cayce's nine realms ruled by the planets. As it evolves, the soul moves higher and higher until it reaches the ultimate realm of spiritual oneness. The first realm, equated with hell, is the place where troubled souls spend a long time before they are compelled to move up to the next level. The second realm, where most souls move directly, is thought of as an intermediate transition between the lower planes of life and hell and the higher perfect realms of the universe. The third level is for those who have worked with their karmic inheritance. The fourth level is that from which evolved souls teach and direct those on Earth. The fifth level is where the soul leaves human consciousness behind. At the sixth plane, the soul is finally aligned with the cosmic consciousness and has no sense of separateness or individuality. Finally, the seventh level, the goal of each soul, is where the soul transcends its own sense of "soulfulness" and reunites with the World Soul and the universe.[86]

Wicca[edit]

The Wiccan afterlife is most commonly described as The Summerland. Here, souls rest, recuperate from life, and reflect on the experiences they had during their lives. After a period of rest, the souls are reincarnated, and the memory of their previous lives is erased. Many Wiccans see The Summerland as a place to reflect on their life actions. It is not a place of reward, but rather the end of a life journey at an end point of incarnations.[87]

Zoroastrianism[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (December 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Zoroastrianism states that the urvan, the disembodied spirit, lingers on earth for three days before departing downward to the kingdom of the dead that is ruled by Yima. For the three days that it rests on Earth, righteous souls sit at the head of their body, chanting the Ustavaiti Gathas with joy, while a wicked person sits at the feet of the corpse, wails and recites the Yasna. Zoroastrianism states that for the righteous souls, a beautiful maiden, which is the personification of the soul's good thoughts, words and deeds, appears. For a wicked person, a very old, ugly, naked hag appears. After three nights, the soul of the wicked is taken by the demon Vizaresa (Vīzarəša), to Chinvat bridge, and is made to go to darkness (hell).

Yima is believed to have been the first king on earth to rule, as well as the first man to die. Inside of Yima's realm, the spirits live a shadowy existence, and are dependent on their own descendants which are still living on Earth. Their descendants are to satisfy their hunger and clothe them, through rituals done on earth.

Rituals which are done on the first three days are vital and important, as they protect the soul from evil powers and give it strength to reach the underworld. After three days, the soul crosses Chinvat bridge which is the Final Judgment of the soul. Rashnu and Sraosha are present at the final judgment. The list is expanded sometimes, and include Vahman and Ormazd. Rashnu is the yazata who holds the scales of justice. If the good deeds of the person outweigh the bad, the soul is worthy of paradise. If the bad deeds outweigh the good, the bridge narrows down to the width of a blade-edge, and a horrid hag pulls the soul in her arms, and takes it down to hell with her.

Misvan Gatu is the "place of the mixed ones" where the souls lead a gray existence, lacking both joy and sorrow. A soul goes here if his/her good deeds and bad deeds are equal, and Rashnu's scale is equal.

Parapsychology[edit]

The Society for Psychical Research was founded in 1882 with the express intention of investigating phenomena relating to Spiritualism and the afterlife. Its members continue to conduct scientific research on the paranormal to this day. Some of the earliest attempts to apply scientific methods to the study of phenomena relating to an afterlife were conducted by this organization. Its earliest members included noted scientists like William Crookes, and philosophers such as Henry Sidgwick and William James.

Parapsychological investigation of the afterlife includes the study of haunting, apparitions of the deceased, instrumental trans-communication, electronic voice phenomena, and mediumship.[88] But also the study of the near death experience. Scientists who have worked in this area include Raymond Moody, Susan Blackmore, Charles Tart, William James, Ian Stevenson, Michael Persinger, Pim van Lommel and Penny Sartori among others.[89][90]

A study conducted in 1901 by physician Duncan MacDougall sought to measure the weight lost by a human when the soul "departed the body" upon death.[91] MacDougall weighed dying patients in an attempt to prove that the soul was material, tangible and thus measurable. Although MacDougall's results varied considerably from "21 grams", for some people this figure has become synonymous with the measure of a soul's mass.[92] The title of the 2003 movie 21 Grams is a reference to MacDougall's findings. His results have never been reproduced, and are generally regarded either as meaningless or considered to have had little if any scientific merit.[93]

Frank Tipler has argued that physics can explain immortality, though such arguments are not falsifiable and thus do not qualify, in Karl Popper's views, as science.[94]

After 25 years of parapsychological research, Susan Blackmore came to the conclusion according to her experiences there is not enough evidence empirical evidence for many of these cases .[95][96], despite the contrary affirm other parapsychologists specialized in the subject.

Philosophy[edit]

Modern philosophy[edit]

There is a view based on the philosophical question of personal identity, termed open individualism by Daniel Kolak. It concludes that individual conscious experience is illusory, and because consciousness continues after death in all conscious beings, you do not die. This position has been supported by notable physicists such as Erwin Schrödinger and Freeman Dyson.[97]

Certain problems arise with the idea of a particular person continuing after death. Peter van Inwagen, in his argument regarding resurrection, notes that the materialist must have some sort of physical continuity.[98] John Hick also raises some questions regarding personal identity in his book, Death and Eternal Life using an example of a person ceasing to exist in one place while an exact replica appears in another. If the replica had all the same experiences, traits, and physical appearances of the first person, we would all attribute the same identity to the second, according to Hick.

Process philosophy[edit]

In the panentheistic model of process philosophy and theology the writers Alfred North Whitehead and Charles Hartshorne rejected that the universe was made of substance, instead reality is composed of living experiences (occasions of experience). According to Hartshorne people do not experience subjective (or personal) immortality in the afterlife, but they do have objective immortality because their experiences live on forever in God, who contains all that was. However other process philosophers such as David Ray Griffin have written that people may have subjective experience after death.[99][100][101][102]

Science[edit]

Regarding the mind–body problem, some neuroscientists take a physicalist position according to which consciousness derives from and/or is reducible to physical phenomena such as neuronal activity occurring in the brain.[103][104] The implication of this premise is that once the brain stops functioning at brain death, consciousness fails to survive and ceases to exist.[105][106] Theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking has rejected concept of an afterlife, saying, "I regard the brain as a computer which will stop working when its components fail. There is no heaven or afterlife for broken down computers; that is a fairy story for people afraid of the dark".[107]

Psychological proposals for the origin of a belief in an afterlife include cognitive disposition, cultural learning, and as an intuitive religious idea.[108] In one study, children were able to recognize the ending of physical, mental, and perceptual activity in death, but were hesitant to conclude the ending of will, self, or emotion in death.[109]

In 2008, a large-scale study conducted by the University of Southhampton involving 2060 patients from 15 hospitals in the United Kingdom, United States and Austria was launched. The AWARE (AWAreness during REsuscitation) study examined the broad range of mental experiences in relation to death. In a large study, researchers also tested the validity of conscious experiences for the first time using objective markers, to determine whether claims of awareness compatible with out-of-body experiences correspond with real or hallucinatory events.[110] The results revealed that 40% of those who survived a cardiac arrest were aware during the time that they were clinically dead and before their hearts were restarted. Dr. Parnia, in the interview stated: “The evidence thus far suggests that in the first few minutes after death, consciousness is not annihilated.[111]

See also[edit]

- Akhirah

- Allegory of the long spoons

- Bardo

- Brig of Dread (Bridge of Dread)

- Cognitivism

- Cryonics

- Dimethyltryptamine

- Empiricism

- Epistemology

- Eternal oblivion

- Exaltation (Mormonism)

- Fate of the unlearned

- Logical positivism

- Mictlan

- Mind uploading

- Omega Point

- Phowa

- Pre-existence

- Rebecca Hensler

- Soul retrieval

- Spiritism

- Suspended animation

- Undead

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Norman C. McClelland 2010, pp. 24–29, 171.

- ^ Mark Juergensmeyer & Wade Clark Roof 2011, pp. 271–72.

- ^ Mark Juergensmeyer & Wade Clark Roof 2011, pp. 271-272.

- ^ Stephen J. Laumakis 2008, pp. 90–99.

- ^ Rita M. Gross (1993). Buddhism After Patriarchy: A Feminist History, Analysis, and Reconstruction of Buddhism. State University of New York Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-4384-0513-1.

- ^ Norman C. McClelland 2010, pp. 102–03.

- ^ see Charles Taliaferro, Paul Draper, Philip L. Quinn, A Companion to Philosophy of Religion. John Wiley and Sons, 2010, p. 640, Google Books

- ^ Gananath Obeyesekere, Imagining Karma: Ethical Transformation in Amerindian, Buddhist, and Greek Rebirth. University of California Press, 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Hitti, Philip K (2007) [1924]. Origins of the Druze People and Religion, with Extracts from their Sacred Writings (New Edition). Columbia University Oriental Studies. 28. London: Saqi. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-86356-690-1

- ^ Heindel, Max (1985) [1939, 1908] The Rosicrucian Christianity Lectures (Collected Works): The Riddle of Life and Death. Oceanside, California. 4th edition. ISBN 0-911274-84-7

- ^ An important recent work discussing the mutual influence of ancient Greek and Indian philosophy regarding these matters is The Shape of Ancient Thought by Thomas McEvilley

- ^ Max Heindel, The Rosicrucian Christianity Lectures (The Riddle of Life and Death), 1908, ISBN 0-911274-84-7

- ^ Max Heindel, Death and Life in Purgatory—Life and Activity in Heaven

- ^ "Life after death – Where do we go after we die?". SSRF English. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ^ Richard P. Taylor, Death and the afterlife: A Cultural Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 2000, ISBN 0-87436-939-8

- ^ Bard, Katheryn (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge.

- ^ Kathryn Demeritt, Ptah's Travels: Kingdoms of Ancient Egypt, 2005, p. 82

- ^ Glennys Howarth, Oliver Leaman, Encyclopedia of death and dying, 2001, p. 238

- ^ Natalie Lunis, Tut's Deadly Tomb, 2010, p. 11

- ^ Fergus Fleming, Alan Lothian, Ancient Egypt's Myths and Beliefs, 2011, p. 96

- ^ "Door to Afterlife found in Egyptian tomb". www.meeja.com.au. 2010-03-30. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ F. P. Retief and L. Cilliers, "Burial customs, the afterlife and the pollution of death in ancient Greece", Acta Theologica 26(2), 2006, p. 45 (PDF).

- ^ Social Studies School Service, Ancient Greece, 2003, pp. 49–51

- ^ Perry L. Westmoreland, Ancient Greek Beliefs, 2007, pp. 68–70

- ^ N. Sabir, Heaven Hell Or, 2010, p. 147

- ^ "Norse Mythology | The Nine Worlds". www.viking-mythology.com. Retrieved 2016-05-11.

- ^ "Fólkvangr, Freyja welcomes you to the Field of the Host". Spangenhelm. 2016-05-20. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ^ a b Smith, Peter (2000). "burial, "death and afterlife", evil, evil spirits, sin". A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 96–97, 118–19, 135–36, 322–23. ISBN 978-1-85168-184-6.

- ^ "Matthew 22:23–33". Biblegateway.com. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ "The New American Bible". Vatican.va. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ Fosdick, Harry Emerson. A guide to understanding the Bible. New York: Harper & Brothers. 1956. p. 276.

- ^ Acts of Paul and Thecla 8:5

- ^ He wrote that a person "may afterward in a quite different manner be very much interested in what is better, when, after his departure out of the body, he gains knowledge of the difference between virtue and vice and finds that he is not able to partake of divinity until he has been purged of the filthy contagion in his soul by the purifying fire" (emphasis added)—Sermon on the Dead, AD 382, quoted in The Roots of Purgatory Archived May 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "purgatory". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Columbia University Press., 2003. Answers.com 06 Jun. 2007.

- ^ "Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ a b "Swedenborg, E. Heaven and Hell (Swedenborg Foundation, 2000)".

- ^ http://stjudetheapostleparish.org/pdf/books/spiritual_combat.pdf#page35

- ^ "limbo – definition of limbo by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". Thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ Ted Campbell, Methodist Doctrine: The Essentials (Abingdon 1999), quoted in Feature article by United Methodist Reporter Managing Editor Robin Russell Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine and in FAQ Belief: What happens immediately after a person dies?

- ^ a b Andrew P. Klager, "Orthodox Eschatology and St. Gregory of Nyssa's De vita Moysis: Transfiguration, Cosmic Unity, and Compassion," In Compassionate Eschatology: The Future as Friend, eds. Ted Grimsrud & Michael Hardin, 230–52 (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2011), 245.

- ^ St. Isaac the Syrian, "Homily 28," In The Ascetical Homilies of Saint Isaac the Syrian, trans. Dana Miller (Brookline, MA: Holy Transfiguration Monastery Press, 1984), 141.

- ^ Fr. Thomas Hopko, "Foreword," in The Orthodox Church, Sergius Bulgakov (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1988), xiii.

- ^ Andrew P. Klager, "Orthodox Eschatology and St. Gregory of Nyssa's De vita Moysis: Transfiguration, Cosmic Unity, and Compassion," In Compassionate Eschatology: The Future as Friend, eds. Ted Grimsrud & Michael Hardin, 230–52 (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2011), 251.

- ^ Kallistos Ware, The Orthodox Church (New York: Penguin, 1997), 262.

- ^ Doctrine and Covenants, Section 76.

- ^ "Kingdoms of Glory".

- ^ "Is Gehenna a Place of Fiery Torment?". The Watchtower: 31. April 1, 2011.

- ^ Reasoning From the Scriptures. pp. 168–75.

- ^ Insight on the Scriptures. 2. pp. 574–76.

- ^ White, E.G. (1858). The great controversy. Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association

- ^ "The Official Site of the Seventh-day Adventist world church". Adventist.org. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ Quran 17:10

- ^ Quran 18:103–106

- ^ Smith, Jane Idleman; Haddad, Yvonne (2008-05-06). Afterlife – Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Oxfordislamicstudies.com. doi:10.1093/0195156498.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-515649-2. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ Mirza Tahir Ahmad (1997). An Elementary Study of Islam. Islam International Publications. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-85372-562-3.

- ^ Ibn Al-Arabi, Muhyiddin (2006). Angela Jaffray, ed. The Universal Tree and The Four Birds. Anqa Publishing. pp. 29n, 50n, 59, 64–68, 73, 75–78, 82, 102.

- ^ Rainwater 1996, p. 819

- ^ Longenecker 2003, p. 188

- ^ Knobel 2011, pp. 205–06

- ^ a b Longenecker 2003, p. 189

- ^ "Tractate Sanhedrin: Interpolated Section: Those Who have no Share in the World to Come". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ "Jehoiakim". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ "soc.culture.jewish FAQ: Jewish Thought (6/12) Section - Question 12.8: What do Jews say happens when a person dies? Do Jews believe in reincarnation? In hell or heaven? Purgato". Faqs.org. 2012-08-08. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ Saadia Gaon in Emunoth ve-Deoth Section vi

- ^ a b Reincarnation in the Jewish Tradition on YouTube

- ^ "Ask the Rabbi – Reincarnation". Judaism.about.com. 2009-12-17. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ Yirmiyahu, Rabbi (2003-07-12). "Reincarnation " Ask! " Ohr Somayach". Ohr.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ Martin Buber, "Legende des Baalschem" in Die Chassidischen Bücher, Hellerau 1928, especially Die niedergestiegene Seele

- ^ "Reincarnation and the Holocaust FAQ". Archived from the original on 2011-07-16.

- ^ "Where does the soul go? New course explores spiritual existence". Middletown, CT. West Hartford News. October 14, 2015.

- ^ Becker, Carl B. (1993). Breaking the circle: death and the afterlife in Buddhism. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. p. viii. ISBN 978-0-585-03949-7.

Buddhists believe in karma and rebirth, and yet they deny the existence of permanent souls.

- ^ Jhaveri, Pujya Gurudevshri Rakeshbhai. "Death the Awakener". Shrimad Rajchandra Mission Dharampur. Shrimad Rajchandra Mission Dharampur. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ http://www.iuscanada.com/journal/archives/2011/j1312p52.pdf

- ^ "Sikhism: What happens after death?".

- ^ Bond, George C. (1992). "Living with Spirits: Death and Afterlife in African Religions". In Obayashi, Hiroshi. Death and Afterlife: Perspectives of World Religions. New York: Greenwood Press. pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-0-313-27906-5.

The entire process of death and burial is simple, without elaborate rituals and beliefs in an afterlife. The social and spiritual existence of the person ends with the burial of the corpse.

- ^ Bond, George C. (1992). "Living with Spirits: Death and Afterlife in African Religions". In Obayashi, Hiroshi. Death and Afterlife: Perspectives of World Religions. New York: Greenwood Press. pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-0-313-27906-5.

The belief in the ancestors remains a strong and active spiritual and moral force in the daily lives of the Yombe; the ancestors are thought to intervene in the affairs of the living.... The afterlife is this world.

- ^ Gottlieb, Alma; Graham, Philip; Gottlieb-Graham, Nathaniel (1998). "Infants, Ancestors, and the Afterlife: Fieldwork's Family Values in Rural West Africa". Anthropology and Humanism. 23 (2): 121. doi:10.1525/ahu.1998.23.2.121.

But Kokora Kouassi, an old friend and respected Master of the Earth in the village of Asagbé, came to our compound early one morning to describe the dream he had just had: he had been visited by the revered and ancient founder of his matriclan, Denju, who confided that Nathaniel was his reincarnation and so should be given his name. The following morning a small ritual was held, and Nathaniel was officially announced to the world not only as Denju but as N'zri Denju—Grandfather Denju—an honorific that came to be used even by Nathaniel's closest playing companions.

- ^ a b Opoku, Kofi Asare (1987). "Death and Immortality in the African Religious Heritage". In Badham, Paul; Badham, Linda. Death and Immortality in the Religions of the World. New York: Paragon House. pp. 9–23. ISBN 978-0-913757-54-3. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ^ Bond, George C. (1992). "Living with Spirits: Death and Afterlife in African Religions". In Obayashi, Hiroshi. Death and Afterlife: Perspectives of World Religions. New York: Greenwood Press. pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-0-313-27906-5.

The process of being born, dying, and moving to a lower level of earth continues through ten lives.

- ^ Bond, George C. (1992). "Living with Spirits: Death and Afterlife in African Religions". In Obayashi, Hiroshi. Death and Afterlife: Perspectives of World Religions. New York: Greenwood Press. pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-0-313-27906-5.

The ancestors are of people, whereas God is external to creation. They are of this world and close to the living. The Yombe believe that the afterlife of the ancestors lies in this world and that they are a spiritual and moral force within it.

- ^ Bond, George C. (1992). "Living with Spirits: Death and Afterlife in African Religions". In Obayashi, Hiroshi. Death and Afterlife: Perspectives of World Religions. New York: Greenwood Press. pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-0-313-27906-5.

Death represents a transition from corporeal to incorporeal life in the religious heritage of Africa and the incorporeal life is taken to be as real as the corporeal.

- ^ Ephirim-Donkor, Anthony (2012). African Religion Defined a Systematic Study of Ancestor Worship among the Akan (2nd ed.). Lanham: University Press of America. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7618-6058-7. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ Bond, Jon (2004-06-13). "Unitarians: unitarian view of afterlife, unitarian universalist association uua, unitarian universalist association". En.allexperts.com. Archived from the original on 2015-11-06. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ Mark W. Harris (2009). The A to Z of Unitarian Universalism. p. 147

- ^ Robyn E. Lebron (2012). Searching for Spiritual Unity ... Can There Be Common Ground? p. 582,

- ^ a b Bartlett, Sarah (2015). The Afterlife Bible: The Complete Guide to Otherworldly Experience. Octopus Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-84181-449-0.

- ^ Solitary Wicca For Life: Complete Guide to Mastering the Craft on Your Own p. 162, Arin Murphy-Hiscock (2005)

- ^ David Fontana (2005): Is there an afterlife. A comprehensive overview of the evidence.

- ^ "Near-death experience in survivors of cardiac arrest: a prospective study in the Netherlands". Profezie3m.altervista.org. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ^ "Nurse writes book on near-death". BBC News. 2008-06-19. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ^ Roach, Mary (2005). Spook – Science Tackles the Afterlife. W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-05962-5.

- ^ Urban Legends – Reference Page (Soul man).

- ^ Park, Robert Ezra (2010). Superstition: Belief in the Age of Science. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-691-14597-6.

- ^ Tipler, Franl, J. (1997). The Physics of Immortality – Modern Cosmology, God and the Resurrection of the Dead. Anchor. ISBN 978-0-385-46799-5.