Charles Taylor (philosopher)

Charles Taylor | |

|---|---|

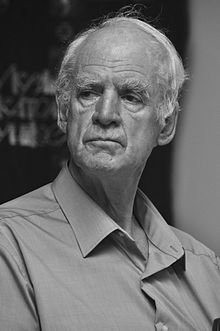

Taylor in 2012 | |

| Born | Charles Margrave Taylor November 5, 1931 |

| Alma mater | |

Notable work |

|

| Spouse(s) | Alba Romer Taylor [1][2](m. 1956; died 1990) |

| Awards |

|

| Era | Contemporary philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Sir Isaiah Berlin |

| Doctoral students | Michael J. Sandel |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas |

|

Influences

| |

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Communitarianism |

|---|

|

Central concepts |

|

Related topics |

| Politics portal |

Charles Margrave Taylor CC GOQ FBA FRSC (born 1931) is a Canadian philosopher from Montreal, Quebec, and professor emeritus at McGill University best known for his contributions to political philosophy, the philosophy of social science, the history of philosophy, and intellectual history. This work has earned him the Kyoto Prize, the Templeton Prize, the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy, and the John W. Kluge Prize.

In 2007, Taylor served with Gérard Bouchard on the Bouchard–Taylor Commission on reasonable accommodation with regard to cultural differences in the province of Quebec. He has also made contributions to moral philosophy, epistemology, hermeneutics, aesthetics, the philosophy of mind, the philosophy of language, and the philosophy of action.[20][21]

Contents

Biography[edit]

Charles Margrave Taylor was born in Montreal, Quebec, on November 5, 1931, to a francophone mother and an anglophone father by whom he was raised bilingually.[22] He attended Selwyn House School from 1941 to 1946[23] and began his undergraduate education at McGill University where he received a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree in history in 1952.[24] He continued his studies at the University of Oxford, first as a Rhodes Scholar at Balliol College, receiving a BA degree with first-class honours in philosophy, politics and economics in 1955, and then as a postgraduate student, receiving a Doctor of Philosophy degree in 1961[2][25] under the supervision of Sir Isaiah Berlin.[26] As an undergraduate student, he started one of the first campaigns to ban thermonuclear weapons in the United Kingdom in 1956,[27] serving as the first president of the Oxford Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.[28]

He succeeded John Plamenatz as Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at the University of Oxford and became a Fellow of All Souls College.[29]

For many years, both before and after Oxford, he was Professor of Political Science and Philosophy at McGill University in Montreal, where he is now professor emeritus.[25][not in citation given] Taylor was also a Board of Trustees Professor of Law and Philosophy at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, for several years after his retirement from McGill.

Taylor was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1986.[30] In 1991, Taylor was appointed to the Conseil de la langue française in the province of Quebec, at which point he critiqued Quebec's commercial sign laws. In 1995, he was made a Companion of the Order of Canada. In 2000, he was made a Grand Officer of the National Order of Quebec. In 2003, he was awarded the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council's Gold Medal for Achievement in Research, which had been the council's highest honour.[31][32] He was awarded the 2007 Templeton Prize for progress towards research or discoveries about spiritual realities, which included a cash award of US$1.5 million.

In 2007 he and Gérard Bouchard were appointed to head a one-year commission of inquiry into what would constitute reasonable accommodation for minority cultures in his home province of Quebec.[33]

In June 2008, he was awarded the Kyoto Prize in the arts and philosophy category. The Kyoto Prize is sometimes referred to as the Japanese Nobel.[34] In 2015, he was awarded the John W. Kluge Prize for Achievement in the Study of Humanity, a prize he shared with philosopher Jürgen Habermas.[35] In 2016, he was awarded the inaugural $1-million Berggruen Prize for being "a thinker whose ideas are of broad significance for shaping human self-understanding and the advancement of humanity."[36]

Views[edit]

In order to understand Taylor's views, it is helpful to understand his philosophical background, especially his writings on Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Taylor rejects naturalism and formalist epistemology. He is part of an influential intellectual tradition of Canadian idealism that includes John Watson, Paxton Young, C. B. Macpherson, and George Grant.[37][dubious ]

In his essay "To Follow a Rule", Taylor explores why people can fail to follow rules, and what kind of knowledge it is that allows a person to successfully follow a rule, such as the arrow on a sign. The intellectualist tradition presupposes that to follow directions, we must know a set of propositions and premises about how to follow directions.[38]

Taylor argues that Wittgenstein's solution is that all interpretation of rules draws upon a tacit background. This background is not more rules or premises, but what Wittgenstein calls "forms of life". More specifically, Wittgenstein says in the Philosophical Investigations that "Obeying a rule is a practice." Taylor situates the interpretation of rules within the practices that are incorporated into our bodies in the form of habits, dispositions, and tendencies.[38]

Following Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Michael Polanyi, and Wittgenstein, Taylor argues that it is mistaken to presuppose that our understanding of the world is primarily mediated by representations. It is only against an unarticulated background that representations can make sense to us. On occasion we do follow rules by explicitly representing them to ourselves, but Taylor reminds us that rules do not contain the principles of their own application: application requires that we draw on an unarticulated understanding or "sense of things"—the background.[38]

Taylor's critique of naturalism[edit]

This section relies too much on references to primary sources. (October 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Taylor defines naturalism as a family of various, often quite diverse theories that all hold "the ambition to model the study of man on the natural sciences."[39]

Philosophically, naturalism was largely popularized and defended by the unity of science movement that was advanced by logical positivist philosophy. In many ways, Taylor's early philosophy springs from a critical reaction against the logical positivism and naturalism that was ascendant in Oxford while he was a student.

Initially, much of Taylor's philosophical work consisted of careful conceptual critiques of various naturalist research programs. This began with his 1964 dissertation The Explanation of Behaviour, which was a detailed and systematic criticism of the behaviourist psychology of B. F. Skinner[40] that was highly influential at mid-century.

From there, Taylor also spread his critique to other disciplines. The essay "Interpretation and the Sciences of Man" was published in 1972 as a critique of the political science of the behavioural revolution advanced by giants of the field like David Easton, Robert Dahl, Gabriel Almond, and Sydney Verba.[41] In an essay entitled "The Significance of Significance: The Case for Cognitive Psychology", Taylor criticized the naturalism he saw distorting the major research program that had replaced B. F. Skinner's behaviourism.[42]

But Taylor also detected naturalism in fields where it was not immediately apparent. For example, in 1978's "Language and Human Nature", he found naturalist distortions in various modern "designative" theories of language,[43] while in Sources of the Self (1989) he found both naturalist error and the deep moral, motivational sources for this outlook in various individualist and utilitarian conceptions of selfhood.

Taylor and hermeneutics[edit]

Concurrent to Taylor's critique of naturalism was his development of an alternative. Indeed, Taylor's mature philosophy begins when as a doctoral student at Oxford he turned away, disappointed, from analytic philosophy in search of other philosophical resources which he found in French and German modern hermeneutics and phenomenology.[44]

The hermeneutic tradition develops a view of human understanding and cognition as centred on the decipherment of meanings (as opposed to, say, foundational theories of brute verification or an apodictic rationalism). Taylor's own philosophical outlook can broadly and fairly be characterized as hermeneutic and has been called engaged hermeneutics.[5] This is clear in his championing of the works of major figures within the hermeneutic tradition such as Wilhelm Dilthey, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Gadamer.[45] It is also evident in his own original contributions to hermeneutic and interpretive theory.[45]

Communitarian critique of liberalism[edit]

Taylor (as well as Alasdair MacIntyre, Michael Walzer, and Michael Sandel) is associated with a communitarian critique of liberal theory's understanding of the "self". Communitarians emphasize the importance of social institutions in the development of individual meaning and identity.

In his 1991 Massey Lecture The Malaise of Modernity, Taylor argued that political theorists—from John Locke and Thomas Hobbes to John Rawls and Ronald Dworkin—have neglected the way in which individuals arise within the context supplied by societies. A more realistic understanding of the "self" recognizes the social background against which life choices gain importance and meaning.

Philosophy and sociology of religion[edit]

Taylor's later work has turned to the philosophy of religion, as evident in several pieces, including the lecture "A Catholic Modernity" and the short monograph "Varieties of Religion Today: William James Revisited".[46]

Taylor's most significant contribution in this field to date is his book A Secular Age which argues against the secularization thesis of Max Weber, Steve Bruce, and others.[47] In rough form, the secularization thesis holds that as modernity (a bundle of phenomena including science, technology, and rational forms of authority) progresses, religion gradually diminishes in influence. Taylor begins from the fact that the modern world has not seen the disappearance of religion but rather its diversification and in many places its growth.[48] He then develops a complex alternative notion of what secularization actually means given that the secularization thesis has not been borne out. In the process, Taylor also greatly deepens his account of moral, political, and spiritual modernity that he had begun in Sources of the Self.

Politics[edit]

Taylor was a candidate for the social democratic New Democratic Party (NDP) in Mount Royal on three occasions in the 1960s, beginning with the 1962 federal election when he came in third behind Liberal Alan MacNaughton. He improved his standing in 1963, coming in second. Most famously, he also lost in the 1965 election to newcomer and future prime minister, Pierre Trudeau. This campaign garnered national attention. Taylor's fourth and final attempt to enter the House of Commons of Canada was in the 1968 federal election, when he came in second as an NDP candidate in the riding of Dollard. In 1994 he coedited a paper on human rights with Vitit Muntarbhorn in Thailand.[49] In 2008, he endorsed the NDP candidate in Westmount—Ville-Marie, Anne Lagacé Dowson. He was also a professor to Canadian politician and former leader of the New Democratic Party Jack Layton.

Taylor served as a vice president of the federal NDP (beginning c. 1965)[28] and was president of its Quebec section.[50]

In 2010, Taylor said multiculturalism was a work in progress that faced challenges. He identified tackling Islamophobia in Canada as the next challenge.[51]

Interlocutors[edit]

- Richard Rorty

- Bernard Williams

- Alasdair MacIntyre: critique of liberalism

- Will Kymlicka

- Martha Nussbaum

- Kwame Appiah: on Taylor's "The Politics of Recognition"

- Hubert Dreyfus: philosophical influence; co-author

- Quentin Skinner

- Talal Asad

- Arjun Appadurai: on the imaginary

- Paul Berman

- William E. Connolly

- Robert Bellah: on Taylor's A Secular Age

- John Milbank

- Stuart Hall

- Catherine Pickstock

- James Tully: on Taylor on "Deep Diversity"

- Jürgen Habermas: shared Kluge prize

Selected works by Taylor[edit]

- Books

- 1964. The Explanation of Behaviour. Routledge Kegan Paul.

- 1975. Hegel. Cambridge University Press.

- 1979. Hegel and Modern Society. Cambridge University Press.

- 1985. Philosophical Papers (2 volumes).

- 1989. Sources of the Self: The Making of Modern Identity. Harvard University Press

- 1992. The Malaise of Modernity, being the published version of Taylor's Massey Lectures. Reprinted in the US as The Ethics of Authenticity. Harvard University Press

- 1993. Reconciling the Solitudes: Essays on Canadian Federalism and Nationalism. McGill-Queen's University Press

- 1994. Multiculturalism: Examining The Politics of Recognition. Princeton University Press

- 1995. Philosophical Arguments. Harvard University Press

- 1999. A Catholic Modernity?.

- 2002. Varieties of Religion Today: William James Revisited. Harvard University Press

- 2004. Modern Social Imaginaries. Duke University Press.

- 2007. A Secular Age. Harvard University Press

- 2011. Dilemmas and Connections: Selected Essays. Harvard University Press.

- 2015. With Hubert Dreyfus, Retrieving Realism. Harvard University Press.

- 2016. The Language Animal: The Full Shape of the Human Linguistic Capacity, Harvard University Press.

- Book chapters

- "The diversity of goods" in Sen, Amartya; Williams, Bernard, eds. (1982). Utilitarianism and beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–144. ISBN 9780511611964.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Palma 2014, pp. 10, 13.

- ^ a b "Fact Sheet – Charles Taylor". Templeton Prize. West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: John Templeton Foundation. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ Bjorn Ramberg; Kristin Gjesdal. "Hermeneutics". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Berlin 1994, p. 1.

- ^ a b Van Aarde 2009.

- ^ Birnbaum 2004, pp. 263–264; Redhead 2004.

- ^ Campbell 2014, p. 58; Redhead 2004.

- ^ Redhead 2004; J. K. A. Smith 2014, p. 18.

- ^ Taylor 1992, p. 14.

- ^ Lehman 2015.

- ^ Busacchi 2015, p. 1.

- ^ Grene 1976, p. 37; Redhead 2004; J. K. A. Smith 2014, p. 18.

- ^ Meijer 2017, p. 267; Meszaros 2016, p. 14; Redhead 2004.

- ^ Apczynski 2014, p. 22.

- ^ Grene 1976, p. 37.

- ^ Abbey 2000, p. 222.

- ^ Rodowick 2015, p. ix.

- ^ Calhoun 2012, pp. 66, 69.

- ^ Campbell 2014, p. 58.

- ^ Abbey 2000.

- ^ "Charles Taylor". Montreal: McGill University. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- ^ Abbey 2016, p. 958; Abbey 2017; N. H. Smith 2002, p. 7.

- ^ "Charles Taylor '46 Receives World's Largest Cash Award". Westmount, Quebec: Selwyn House School. March 15, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ^ Abbey 2016, p. 958.

- ^ a b Mason 1996.

- ^ Ancelovici & Dupuis-Déri 2001, p. 260.

- ^ N. H. Smith 2002, p. 7.

- ^ a b Palma 2014, p. 11.

- ^ Abbey 2016, p. 958; Miller 2014, p. 165.

- ^ American Academy of Arts and Sciences, p. 536.

- ^ "Prizes". Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- ^ "Prizes: Previous Winners". Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- ^ "Home". Montreal: Consultation Commission on Accommodation Practices Related to Cultural Differences. Archived from the original on July 1, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- ^ "Dr. Charles Taylor to Receive Inamori Foundation's 24th Annual Kyoto Prize for Lifetime Achievement in 'Arts and Philosophy'" (Press release). Kyoto, Japan: Inamori Foundation. June 20, 2008. Archived from the original on April 21, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ "Philosophers Habermas and Taylor to Share $1.5 Million Kluge Prize" (Press release). Washington: Library of Congress. August 11, 2015. ISSN 0731-3527. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ Schuessler, Jennifer (October 4, 2016). "Canadian Philosopher Wins $1 Million Prize". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ Meynell 2011.

- ^ a b c Taylor 1995.

- ^ Taylor 1985a, p. 1.

- ^ Taylor 1964.

- ^ Taylor 1985b.

- ^ Taylor 1983.

- ^ Taylor 1985c.

- ^ "Interview with Charles Taylor: The Malaise of Modernity" by David Cayley: http://www.cbc.ca/ideas/episodes/2011/04/11/the-malaise-of-modernity-part-1---5/

- ^ a b Taylor 1985d.

- ^ A Catholic Modernity?: Charles Taylor's Marianist Award Lecture, ed. James Heft (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999); Varieties of Religion Today (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002).

- ^ Taylor 2007.

- ^ Taylor 2007, pp. 1–22.

- ^ Muntarbhorn & Taylor 1994.

- ^ Abbey 2000, p. 6; Anctil 2011, p. 119.

- ^ "Part 5: 10 Leaders on How to Change Multiculturalism". Our Time to Lead. The Globe and Mail. June 21, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

References[edit]

- Abbey, Ruth (2000). Charles Taylor. Abingdon, England: Routledge (published 2014). ISBN 978-1-317-49019-7.

- ——— (2016). "Taylor, Charles (1931–)". In Shook, John R. The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Philosophers in America: From 1600 to the Present. London: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 958ff. ISBN 978-1-4725-7056-7.

- ——— (2017). "Taylor, Charles (1931– )". Dictionnaire de la Philosophie politique (in French). Encyclopædia Universalis. ISBN 978-2-341-00704-7.

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences. "T" (PDF). Book of Members, 1780–2012. American Academy of Arts and Sciences. pp. 533–552. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- Ancelovici, Marcos; Dupuis-Déri, Francis (2001). "Charles Taylor". In Elliott, Anthony; Turner, Bryan S. Profiles in Contemporary Social Theory. London: SAGE Publications. pp. 260–269. ISBN 978-0-7619-6589-3.

- Anctil, Pierre (2011). "Introduction". In Adelman, Howard; Anctil, Pierre. Religion, Culture, and the State: Reflections on the Bouchard–Taylor Report. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 3–15. ISBN 978-1-4426-1144-3.

- Apczynski, John V. (2014). "The Projects of Michael Polanyi and Charles Taylor" (PDF). Tradition and Discovery. 41 (1): 21–32. doi:10.5840/traddisc2014/20154115. ISSN 2154-1566.

- Berlin, Isaiah (1994). "Introduction". In Tully, James. Philosophy in an Age of Pluralism: The Philosophy of Charles Taylor in Question. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-521-43742-4.

- Birnbaum, Pierre (2004). "Entre universalisme et multiculturalisme : ne modèle français dans la théorie politique contemporaine" [Between Universalism and Multiculturalism: The French Model in Contemporary Political Theory] (PDF). In Dieckhoff, Alain. La constellation des appartenances : nationalisme, libéralisme et pluralisme [The Politics of Belonging: Nationalism, Liberalism, and Pluralism] (in French). Paris: Presses de Sciences Po. pp. 257–280. ISBN 978-2-7246-0932-5. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- Busacchi, Vinicio (2015). The Recognition Principle: A Philosophical Perspective Between Psychology, Sociology and Politics. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-7586-8.

- Calhoun, Craig (2012). "Craig Calhoun". In Nickel, Patricia Mooney. North American Critical Theory After Postmodernism: Contemporary Dialogues. Interviewed by Nickel, Patricia Mooney. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 62–87. ISBN 978-0-230-36927-6.

- Campbell, Catherine Galko (2014). Persons, Identity, and Political Theory: A Defense of Rawlsian Political Identity. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7917-4. ISBN 978-94-007-7917-4.

- Grene, Marjorie (1976). Philosophy in and out of Europe. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03121-0.

- Lehman, Glen (2015). Charles Taylor's Ecological Conversations: Politics, Commonalities and the Natural Environment. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-52478-2.

- Mason, Richard (1996). "Taylor, Charles Margrave". In Brown, Stuart; Collinson, Diané; Wilkinson, Robert. Biographical Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Philosophers. London: Routledge. pp. 774–776. ISBN 978-0-415-06043-1.

- Meijer, Michiel (2017). "Human-Related, Not Human-Controlled: Charles Taylor on Ethics and Ontology". International Philosophical Quarterly. 57 (3): 267–285. doi:10.5840/ipq20173679. ISSN 0019-0365.

- Meszaros, Julia T. (2016). Selfless Love and Human Flourishing in Paul Tillich and Iris Murdoch. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198765868.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-876586-8.

- Meynell, Robert (2011). Canadian Idealism and the Philosophy of Freedom: C.B. Macpherson, George Grant and Charles Taylor. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-3798-9.

- Miller, David (2014). "Political Theory, Philosophy, and the Social Sciences: Five Chichele Professors". In Hood, Christopher; King, Desmond; Peele, Gillian. Forging a Discipline: A Critical Assessment of Oxford's Development of the Study of Politics and International Relations in Comparative Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 165ff. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199682218.003.0009. ISBN 978-0-19-968221-8.

- Muntarbhorn, Vitit; Taylor, Charles (1994). Road to Democracy: Human Rights and Human Development in Thailand. Montreal: International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development.

- Palma, Anthony Joseph (2014). Recognition of Diversity: Charles Taylor's Educational Thought (PhD thesis). Toronto: University of Toronto. hdl:1807/65711.

- Redhead, Mark (2004). "Review of Charles Taylor, Edited by Ruth Abbey". Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews. ISSN 1538-1617. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- Rodowick, D. N. (2015). Philosophy's Artful Conversation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-41667-3.

- Smith, James K. A. (2014). How (Not) to Be Secular: Reading Charles Taylor. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-8028-6761-2.

- Smith, Nicholas H. (2002). Charles Taylor: Meaning, Morals and Modernity. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7456-6859-8.

- Taylor, Charles (1964). The Explanation of Behaviour. International Library of Philosophy and Scientific Method. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- ——— (1983). "The Significance of Significance: The Case for Cognitive Psychology". In Mitchell, Sollace; Rosen, Michael. The Need for Interpretation: Contemporary Conceptions of the Philosopher's Task. New Jersey: Humanities Press. pp. 141–169. ISBN 978-0-391-02825-8.

- ——— (1985a). "Introduction". In Taylor, Charles. Human Agency and Language. Philosophical Papers. 1. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-0-521-31750-4.

- ——— (1985b) [1972]. "Interpretation and the Sciences of Man". In Taylor, Charles. Philosophy and the Human Sciences. Philosophical Papers. 2. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–57.

- ——— (1985c) [1978]. "Language and Human Nature". In Taylor, Charles. Human Agency and Language. Philosophical Papers. 1. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 215–247. ISBN 978-0-521-31750-4.

- ——— (1985d). "Self-Interpreting Animals". In Taylor, Charles. Human Agency and Language. Philosophical Papers. 1. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 45–76. ISBN 978-0-521-31750-4.

- ——— (1992) [1991]. The Ethics of Authenticity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-26863-0.

- ——— (1995). "To Follow a Rule". Philosophical Arguments. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 165–180. ISBN 978-0-674-66477-7.

- ——— (2007). A Secular Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02676-6.

- Van Aarde, Andries G. (2009). "Postsecular Spirituality, Engaged Hermeneutics, and Charles Taylor's Notion of Hypergoods". HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies. 65 (1): 209–216. doi:10.4102/hts.v65i1.166. ISSN 2072-8050.

Further reading[edit]

- Barrie, John A. (1996). "Probing Modernity". Quadrant. Vol. 40 no. 5. pp. 82–83. ISSN 0033-5002.

- Blakely, Jason (2016). Alasdair MacIntyre, Charles Taylor, and the Demise of Naturalism: Reunifying Political Theory and Social Science. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 978-0-268-10064-3.

- Gagnon, Bernard (2002). La philosophie morale et politique de Charles Taylor [The Moral and Political Philosophy of Charles Taylor] (in French). Quebec City, Quebec: Presses de l'Université Laval. ISBN 978-2-7637-7866-2.

- McKenzie, Germán (2017). Interpreting Charles Taylor's Social Theory on Religion and Secularization. Sophia Studies in Cross-Cultural Philosophy of Traditions and Cultures. 20. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47700-8. ISBN 978-3-319-47698-8. ISSN 2211-1107.

- Meijer, Michiel (2018). Charles Taylor's Doctrine of Strong Evaluation: Ethics and Ontology in a Scientific Age. London: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-78660-400-2.

- Perreau-Saussine, Émile (2005). "Une spiritualité libérale? Alasdair MacIntyre et Charles Taylor en conversation" [A Liberal Spirituality? Alasdair MacIntyre and Charles Taylor in Conversation] (PDF). Revue Française de Science Politique (in French). Presses de Sciences Po. 55 (2): 299–315. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- Redhead, Mark (2002). Charles Taylor: Thinking and Living Deep Diversity. Twentieth-Century Political Thinkers. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-2126-1.

- Skinner, Quentin (1991). "Who Are 'We'? Ambiguities of the Modern Self". Inquiry. 34 (2): 133–153. doi:10.1080/00201749108602249.

- Svetelj, Tone (2012). Rereading Modernity: Charles Taylor on Its Genesis and Prospects (PhD thesis). Chestnut Hills, Massachusetts: Boston College. hdl:2345/3853.

- Temelini, Michael (2014). "Dialogical Approaches to Struggles over Recognition and Distribution". Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy. 17 (4): 423–447. doi:10.1080/13698230.2013.763517. ISSN 1743-8772.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Charles Taylor (philosopher) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Taylor (philosopher). |

- A comprehensive bibliography that includes all of Taylor's works as well as secondary literature on Taylor's philosophy, interviews, media, and resources.

- A wide-ranging interview with Charles Taylor, including Taylor's thoughts about his own intellectual development.

- An Interview with Charles Taylor Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3

- The Immanent Frame a blog with posts by Taylor, Robert Bellah, and others concerning Taylor's book A Secular Age

- Text of Taylor's essay "Overcoming Epistemology"

- Links to secondary sources, reviews of Taylor's works, reading notes

- Lecture notes to Charles Taylor's talk on Religion and Violence (with a link to the audio) Nov 2004

- Lecture notes to Charles Taylor's talk on 'An End to Mediational Epistemology', Nov 2004

- Study guide to Philosophical Arguments and Philosophical Papers 2

- Templeton Prize announcement

- Short essay by Dene Baker, philosophers.co.uk

- Taylor's famous essay The Politics of Recognition

- Charles Taylor on McGill Yearbook when he graduated in 1952

- Online videos of Charles Taylor

- Berggruen Prize Winner Charles Taylor on the Big Questions; series of videos produced by the Berggruen Institute

- Can Human Action Be Explained?; Charles Taylor gives a lecture at Columbia University

- A Political Ethic of Solidarity on YouTube; Charles Taylor gives a lecture on a future politics self-consciously based on differing views and foundations in Milan

- "Spiritual Forgetting" on YouTube; Charles Taylor at awarding of Templeton Prize

- (in French) «La religion dans la Cité des modernes : un divorce sans issue?» (14/10/2006)[permanent dead link] ; Charles Taylor and Pierre Manent, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal, «Les grandes conférences Argument».

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John Plamenatz |

Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory 1976–1981 |

Succeeded by G. A. Cohen |

| Awards | ||

| Preceded by J. Bryan Hehir |

Marianist Award for Intellectual Contributions 1996 |

Succeeded by Gustavo Gutiérrez |

| New award | SSHRC Gold Medal for Achievement in Research 2003 |

Succeeded by Alex Michalos |

| Preceded by John D. Barrow |

Templeton Prize 2007 |

Succeeded by Michał Heller |

| Preceded by Pina Bausch |

Kyoto Prize in Arts and Philosophy 2008 |

Succeeded by Pierre Boulez |

| Preceded by Fernando Henrique Cardoso |

Kluge Prize 2015 With: Jürgen Habermas |

Succeeded by Drew Gilpin Faust |

| New award | Berggruen Prize 2016 |

Succeeded by The Baroness O'Neill of Bengarve |

- 1931 births

- 20th-century philosophers

- 21st-century philosophers

- Action theorists

- Analytic philosophers

- Anglophone Quebec people

- Canadian philosophers

- Canadian political philosophers

- Canadian political theorists

- Canadian Rhodes Scholars

- Chichele Professors of Social and Political Theory

- Companions of the Order of Canada

- Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Fellows of the British Academy

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Canada

- Grand Officers of the National Order of Quebec

- Heidegger scholars

- Kyoto laureates in Arts and Philosophy

- Living people

- McGill University alumni

- Moral philosophers

- New Democratic Party candidates for the Canadian House of Commons

- Northwestern University faculty

- Ontologists

- People from Montreal

- Philosophers of social science

- Quebec candidates for Member of Parliament

- Roman Catholic philosophers

- Scholars of nationalism

- Secularism

- Templeton Prize laureates