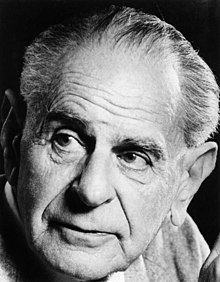

Karl Popper

Sir Karl Raimund Popper CH FBA FRS[9] (28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994) was an Austrian-British philosopher and professor.[10][11][12]

Generally regarded as one of the 20th century's greatest philosophers of science,[13][14][15] Popper is known for his rejection of the classical inductivist views on the scientific method in favour of empirical falsification. A theory in the empirical sciences can never be proven, but it can be falsified, meaning that it can and should be scrutinised by decisive experiments. Popper is also known for his opposition to the classical justificationist account of knowledge, which he replaced with critical rationalism, namely "the first non-justificational philosophy of criticism in the history of philosophy".[16]

In political discourse, he is known for his vigorous defence of liberal democracy and the principles of social criticism that he came to believe made a flourishing open society possible. His political philosophy embraces ideas from all major democratic political ideologies and attempts to reconcile them, namely socialism/social democracy, libertarianism/classical liberalism and conservatism.[3]

Contents

- 1 Personal life

- 2 Honours and awards

- 3 Philosophy

- 4 Influence

- 5 Criticism

- 6 Bibliography

- 7 Filmography

- 8 See also

- 9 References

- 10 Further reading

- 11 External links

Personal life[edit]

Family and training[edit]

Karl Popper was born in Vienna (then in Austria-Hungary) in 1902 to upper-middle-class parents. All of Popper's grandparents were Jewish, but they were not devout and as part of the cultural assimilation process the Popper family converted to Lutheranism before he was born[17][18] and so he received a Lutheran baptism.[19][20] His father Simon Siegmund Carl Popper was a lawyer from Bohemia and a doctor of law at the Vienna University while his mother Jenny Schiff was of Silesian and Hungarian descent. Popper's uncle was the Austrian philosopher Josef Popper-Lynkeus. After establishing themselves in Vienna, the Poppers made a rapid social climb in Viennese society as Popper's father became a partner in the law firm of Vienna's liberal mayor Raimund Grübl and after Grübl's death in 1898 took over the business. Popper received his middle name after Raimund Grübl.[17] (Popper himself in his autobiography erroneously recalls that Grübl's first name was Carl).[21] His father was a bibliophile who had 12,000–14,000 volumes in his personal library[22] and took an interest in philosophy, the classics, and social and political issues.[13] Popper inherited both the library and the disposition from him.[23] Later, he would describe the atmosphere of his upbringing as having been "decidedly bookish."[13]

Popper left school at the age of 16 and attended lectures in mathematics, physics, philosophy, psychology and the history of music as a guest student at the University of Vienna. In 1919, Popper became attracted by Marxism and subsequently joined the Association of Socialist School Students.[13] He also became a member of the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Austria, which was at that time a party that fully adopted the Marxist ideology.[13] After the street battle in the Hörlgasse on 15 June 1919, when police shot eight of his unarmed party comrades, he became disillusioned by what he saw as the "pseudo-scientific" historical materialism of Marx, abandoned the ideology, and remained a supporter of social liberalism throughout his life.[3]

He worked in street construction for a short amount of time, but was unable to cope with the heavy labour. Continuing to attend university as a guest student, he started an apprenticeship as a cabinetmaker, which he completed as a journeyman. He was dreaming at that time of starting a daycare facility for children, for which he assumed the ability to make furniture might be useful. After that he did voluntary service in one of psychoanalyst Alfred Adler's clinics for children. In 1922, he did his matura by way of a second chance education and finally joined the University as an ordinary student. He completed his examination as an elementary teacher in 1924 and started working at an after-school care club for socially endangered children. In 1925, he went to the newly founded Pädagogisches Institut and continued studying philosophy and psychology. Around that time he started courting Josefine Anna Henninger, who later became his wife.

In 1928, he earned a doctorate in psychology, under the supervision of Karl Bühler. His dissertation was titled Zur Methodenfrage der Denkpsychologie (On Questions of Method in the Psychology of Thinking).[24] In 1929, he obtained the authorisation to teach mathematics and physics in secondary school, which he started doing. He married his colleague Josefine Anna Henninger (1906–1985) in 1930. Fearing the rise of Nazism and the threat of the Anschluss, he started to use the evenings and the nights to write his first book Die beiden Grundprobleme der Erkenntnistheorie (The Two Fundamental Problems of the Theory of Knowledge). He needed to publish one to get some academic position in a country that was safe for people of Jewish descent. However, he ended up not publishing the two-volume work, but a condensed version of it with some new material, Logik der Forschung (The Logic of Scientific Discovery), in 1934. Here, he criticised psychologism, naturalism, inductivism, and logical positivism, and put forth his theory of potential falsifiability as the criterion demarcating science from non-science. In 1935 and 1936, he took unpaid leave to go to the United Kingdom for a study visit.[25]

Academic life[edit]

In 1937, Popper finally managed to get a position that allowed him to emigrate to New Zealand, where he became lecturer in philosophy at Canterbury University College of the University of New Zealand in Christchurch. It was here that he wrote his influential work The Open Society and Its Enemies. In Dunedin he met the Professor of Physiology John Carew Eccles and formed a lifelong friendship with him. In 1946, after the Second World War, he moved to the United Kingdom to become reader in logic and scientific method at the London School of Economics. Three years later, in 1949, he was appointed professor of logic and scientific method at the University of London. Popper was president of the Aristotelian Society from 1958 to 1959. He retired from academic life in 1969, though he remained intellectually active for the rest of his life. In 1985, he returned to Austria so that his wife could have her relatives around her during the last months of her life; she died in November that year. After the Ludwig Boltzmann Gesellschaft failed to establish him as the director of a newly founded branch researching the philosophy of science, he went back again to the United Kingdom in 1986, settling in Kenley, Surrey.[9]

Death[edit]

Popper died of "complications of cancer, pneumonia and kidney failure" in Kenley at the age of 92 on 17 September 1994.[26][27] He had been working continuously on his philosophy until two weeks before, when he suddenly fell terminally ill.[28] After cremation, his ashes were taken to Vienna and buried at Lainzer cemetery adjacent to the ORF Centre, where his wife Josefine Anna Popper (called 'Hennie') had already been buried.[29] Popper's estate is managed by his secretary and personal assistant Melitta Mew and her husband Raymond. Popper's manuscripts went to the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, partly during his lifetime and partly as supplementary material after his death. Klagenfurt University has Popper's library, including his precious bibliophilia, as well as hard copies of the original Hoover material and microfilms of the supplementary material. The remaining parts of the estate were mostly transferred to The Karl Popper Charitable Trust.[30] In October 2008 Klagenfurt University acquired the copyrights from the estate.

Popper and his wife had chosen not to have children because of the circumstances of war in the early years of their marriage. Popper commented that this "was perhaps a cowardly but in a way a right decision".[31]

Honours and awards[edit]

Popper won many awards and honours in his field, including the Lippincott Award of the American Political Science Association, the Sonning Prize, the Otto Hahn Peace Medal of the United Nations Association of Germany in Berlin and fellowships in the Royal Society,[9] British Academy, London School of Economics, King's College London, Darwin College, Cambridge, Austrian Academy of Sciences and Charles University, Prague. Austria awarded him the Grand Decoration of Honour in Gold for Services to the Republic of Austria in 1986, and the Federal Republic of Germany its Grand Cross with Star and Sash of the Order of Merit, and the peace class of the Order Pour le Mérite. He received the Humanist Laureate Award from the International Academy of Humanism.[32] He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1965,[33] and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1976.[9] He was invested with the Insignia of a Companion of Honour in 1982.[34]

Other awards and recognition for Popper included the City of Vienna Prize for the Humanities (1965), Karl Renner Prize (1978), Austrian Decoration for Science and Art (1980), Dr. Leopold Lucas Prize of the University of Tübingen (1980), Ring of Honour of the City of Vienna (1983) and the Premio Internazionale of the Italian Federico Nietzsche Society (1988). In 1989, he was the first awarded the Prize International Catalonia for "his work to develope cultural, scientific and human values all around the world".[35] In 1992, he was awarded the Kyoto Prize in Arts and Philosophy for "symbolising the open spirit of the 20th century"[36] and for his "enormous influence on the formation of the modern intellectual climate".[36]

Philosophy[edit]

Background to Popper's ideas[edit]

Popper's rejection of Marxism during his teenage years left a profound mark on his thought. He had at one point joined a socialist association, and for a few months in 1919 considered himself a communist.[37] Although it's known that Popper worked as an office boy at the communist headquarters, whether or not he ever became a member of the Communist Party is unclear.[38] During this time he became familiar with the Marxist view of economics, class conflict, and history.[13] Although he quickly became disillusioned with the views expounded by Marxism, his flirtation with the ideology led him to distance himself from those who believed that spilling blood for the sake of a revolution was necessary. He came to realise that when it came to sacrificing human lives, one was to think and act with extreme prudence.

The failure of democratic parties to prevent fascism from taking over Austrian politics in the 1920s and 1930s traumatised Popper. He suffered from the direct consequences of this failure, since events after the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria by the German Reich in 1938, forced him into permanent exile. His most important works in the field of social science—The Poverty of Historicism (1944) and The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945)—were inspired by his reflection on the events of his time and represented, in a sense, a reaction to the prevalent totalitarian ideologies that then dominated Central European politics. His books defended democratic liberalism as a social and political philosophy. They also represented extensive critiques of the philosophical presuppositions underpinning all forms of totalitarianism.[13]

Popper believed that there was a contrast between the theories of Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler, which he considered non-scientific, and the revolution set off by Albert Einstein's theory of relativity in physics in the early 20th century. Popper thought that Einstein's theory, as a theory properly grounded in scientific thought and method, was highly "risky", in the sense that it was possible to deduce consequences from it which were, in the light of the then-dominant Newtonian physics, highly improbable (e.g., that light is deflected towards solid bodies—confirmed by Eddington's experiments in 1919), and which would, if they turned out to be false, falsify the whole theory. In contrast he thought that nothing could, even in principle, falsify psychoanalytic theories. He thus came to the conclusion that they had more in common with primitive myths than with genuine science.[13]

This led Popper to conclude that what were regarded[by whom?] as the remarkable strengths of psychoanalytical theories were actually their weaknesses. Psychoanalytical theories were crafted in a way that made them able to refute any criticism and to give an explanation for every possible form of human behaviour. The nature of such theories made it impossible for any criticism or experiment—even in principle—to show them to be false.[13] When Popper later tackled the problem of demarcation in the philosophy of science, this conclusion led him to posit that the strength of a scientific theory lies in its both being susceptible to falsification, and not actually being falsified by criticism made of it. He considered that if a theory cannot, in principle, be falsified by criticism, it is not a scientific theory.[39]

Philosophy of science[edit]

Falsifiability/problem of demarcation[edit]

Popper coined the term "critical rationalism" to describe his philosophy. Concerning the method of science, the term indicates his rejection of classical empiricism, and the classical observationalist-inductivist account of science that had grown out of it. Popper argued strongly against the latter, holding that scientific theories are abstract in nature, and can be tested only indirectly, by reference to their implications. He also held that scientific theory, and human knowledge generally, is irreducibly conjectural or hypothetical, and is generated by the creative imagination to solve problems that have arisen in specific historico-cultural settings.

Logically, no number of positive outcomes at the level of experimental testing can confirm a scientific theory, but a single counterexample is logically decisive; it shows the theory, from which the implication is derived, to be false. To say that a given statement (e.g., the statement of a law of some scientific theory)—call it "T"—is "falsifiable" does not mean that "T" is false. Rather, it means that, if "T" is false, then (in principle), "T" could be shown to be false, by observation or by experiment. Popper's account of the logical asymmetry between verification and falsifiability lies at the heart of his philosophy of science. It also inspired him to take falsifiability as his criterion of demarcation between what is, and is not, genuinely scientific: a theory should be considered scientific if, and only if, it is falsifiable. This led him to attack the claims of both psychoanalysis and contemporary Marxism to scientific status, on the basis that their theories are not falsifiable.

Popper also wrote extensively against the famous Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics. He strongly disagreed with Niels Bohr's instrumentalism and supported Albert Einstein's realist approach to scientific theories about the universe. Popper's falsifiability resembles Charles Peirce's nineteenth-century fallibilism. In Of Clocks and Clouds (1966), Popper remarked that he wished he had known of Peirce's work earlier.

In All Life is Problem Solving, Popper sought to explain the apparent progress of scientific knowledge—that is, how it is that our understanding of the universe seems to improve over time. This problem arises from his position that the truth content of our theories, even the best of them, cannot be verified by scientific testing, but can only be falsified. Again, in this context the word "falsified" does not refer to something being "fake"; rather, that something can be (i.e., is capable of being) shown to be false by observation or experiment. Some things simply do not lend themselves to being shown to be false, and therefore, are not falsifiable. If so, then how is it that the growth of science appears to result in a growth in knowledge? In Popper's view, the advance of scientific knowledge is an evolutionary process characterised by his formula:[40][41]

In response to a given problem situation (), a number of competing conjectures, or tentative theories (), are systematically subjected to the most rigorous attempts at falsification possible. This process, error elimination (), performs a similar function for science that natural selection performs for biological evolution. Theories that better survive the process of refutation are not more true, but rather, more "fit"—in other words, more applicable to the problem situation at hand (). Consequently, just as a species' biological fitness does not ensure continued survival, neither does rigorous testing protect a scientific theory from refutation in the future. Yet, as it appears that the engine of biological evolution has, over many generations, produced adaptive traits equipped to deal with more and more complex problems of survival, likewise, the evolution of theories through the scientific method may, in Popper's view, reflect a certain type of progress: toward more and more interesting problems (). For Popper, it is in the interplay between the tentative theories (conjectures) and error elimination (refutation) that scientific knowledge advances toward greater and greater problems; in a process very much akin to the interplay between genetic variation and natural selection.

Falsification/problem of induction[edit]

Among his contributions to philosophy is his claim to have solved the philosophical problem of induction. He states that while there is no way to prove that the sun will rise, it is possible to formulate the theory that every day the sun will rise; if it does not rise on some particular day, the theory will be falsified and will have to be replaced by a different one. Until that day, there is no need to reject the assumption that the theory is true. Nor is it rational according to Popper to make instead the more complex assumption that the sun will rise until a given day, but will stop doing so the day after, or similar statements with additional conditions.

Such a theory would be true with higher probability, because it cannot be attacked so easily: to falsify the first one, it is sufficient to find that the sun has stopped rising; to falsify the second one, one additionally needs the assumption that the given day has not yet been reached. Popper held that it is the least likely, or most easily falsifiable, or simplest theory (attributes which he identified as all the same thing) that explains known facts that one should rationally prefer. His opposition to positivism, which held that it is the theory most likely to be true that one should prefer, here becomes very apparent. It is impossible, Popper argues, to ensure a theory to be true; it is more important that its falsity can be detected as easily as possible.

Popper and David Hume agreed that there is often a psychological belief that the sun will rise tomorrow, but both denied that there is logical justification for the supposition that it will, simply because it always has in the past. Popper writes, "I approached the problem of induction through Hume. Hume, I felt, was perfectly right in pointing out that induction cannot be logically justified." (Conjectures and Refutations, p. 55)

Rationality[edit]

Popper held that rationality is not restricted to the realm of empirical or scientific theories, but that it is merely a special case of the general method of criticism, the method of finding and eliminating contradictions in knowledge without ad-hoc-measures. According to this view, rational discussion about metaphysical ideas, about moral values and even about purposes is possible. Popper's student W.W. Bartley III tried to radicalise this idea and made the controversial claim that not only can criticism go beyond empirical knowledge, but that everything can be rationally criticised.

To Popper, who was an anti-justificationist, traditional philosophy is misled by the false principle of sufficient reason. He thinks that no assumption can ever be or needs ever to be justified, so a lack of justification is not a justification for doubt. Instead, theories should be tested and scrutinised. It is not the goal to bless theories with claims of certainty or justification, but to eliminate errors in them. He writes, "there are no such things as good positive reasons; nor do we need such things [...] But [philosophers] obviously cannot quite bring [themselves] to believe that this is my opinion, let alone that it is right." (The Philosophy of Karl Popper, p. 1043)

Philosophy of arithmetic[edit]

Popper's principle of falsifiability runs into prima facie difficulties when the epistemological status of mathematics is considered. It is difficult to conceive how simple statements of arithmetic, such as "2 + 2 = 4", could ever be shown to be false. If they are not open to falsification they can not be scientific. If they are not scientific, it needs to be explained how they can be informative about real world objects and events.

Popper's solution[42] was an original contribution in the philosophy of mathematics. His idea was that a number statement such as "2 apples + 2 apples = 4 apples" can be taken in two senses. In one sense it is irrefutable and logically true, in the second sense it is factually true and falsifiable. Concisely, the pure mathematics "2 + 2 = 4" is always true, but, when the formula is applied to real-world apples, it is open to falsification.[43]

Political philosophy[edit]

In The Open Society and Its Enemies and The Poverty of Historicism, Popper developed a critique of historicism and a defence of the "Open Society". Popper considered historicism to be the theory that history develops inexorably and necessarily according to knowable general laws towards a determinate end. He argued that this view is the principal theoretical presupposition underpinning most forms of authoritarianism and totalitarianism. He argued that historicism is founded upon mistaken assumptions regarding the nature of scientific law and prediction. Since the growth of human knowledge is a causal factor in the evolution of human history, and since "no society can predict, scientifically, its own future states of knowledge",[44] it follows, he argued, that there can be no predictive science of human history. For Popper, metaphysical and historical indeterminism go hand in hand.

In his early years Popper was impressed by Marxism, whether of Communists or socialists. An event that happened in 1919 had a profound effect on him: During a riot, caused by the Communists, the police shot several unarmed people, including some of Popper's friends, when they tried to free party comrades from prison. The riot had, in fact, been part of a plan by which leaders of the Communist party with connections to Béla Kun tried to take power by a coup; Popper did not know about this at that time. However, he knew that the riot instigators were swayed by the Marxist doctrine that class struggle would produce vastly more dead men than the inevitable revolution brought about as quickly as possible, and so had no scruples to put the life of the rioters at risk to achieve their selfish goal of becoming the future leaders of the working class. This was the start of his later criticism of historicism.[45][46] Popper began to reject Marxist historicism, which he associated with questionable means, and later socialism, which he associated with placing equality before freedom (to the possible disadvantage of equality).[47]

In 1947, Popper co-founded the Mont Pelerin Society, with Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, Ludwig von Mises and others, although he did not fully agree with the think tank's charter and ideology. Specifically, he unsuccessfully recommended that socialists should be invited to participate, and that emphasis should be put on a hierarchy of humanitarian values rather than advocacy of a free market as envisioned by classical liberalism.[48]

The paradox of tolerance[edit]

Although Popper was an advocate of toleration, he said that intolerance should not be tolerated, for if tolerance allowed intolerance to succeed completely, tolerance would be threatened. In The Open Society and Its Enemies, he argued:

Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them. In this formulation, I do not imply, for instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise. But we should claim the right to suppress them if necessary even by force; for it may easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument, but begin by denouncing all argument; they may forbid their followers to listen to rational argument, because it is deceptive, and teach them to answer arguments by the use of their fists or pistols. We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant. We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law, and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, in the same way as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or to the revival of the slave trade, as criminal.[49][50][51][52]

Metaphysics[edit]

Truth[edit]

As early as 1934, Popper wrote of the search for truth as "one of the strongest motives for scientific discovery."[53] Still, he describes in Objective Knowledge (1972) early concerns about the much-criticised notion of truth as correspondence. Then came the semantic theory of truth formulated by the logician Alfred Tarski and published in 1933. Popper wrote of learning in 1935 of the consequences of Tarski's theory, to his intense joy. The theory met critical objections to truth as correspondence and thereby rehabilitated it. The theory also seemed, in Popper's eyes, to support metaphysical realism and the regulative idea of a search for truth.

According to this theory, the conditions for the truth of a sentence as well as the sentences themselves are part of a metalanguage. So, for example, the sentence "Snow is white" is true if and only if snow is white. Although many philosophers have interpreted, and continue to interpret, Tarski's theory as a deflationary theory, Popper refers to it as a theory in which "is true" is replaced with "corresponds to the facts". He bases this interpretation on the fact that examples such as the one described above refer to two things: assertions and the facts to which they refer. He identifies Tarski's formulation of the truth conditions of sentences as the introduction of a "metalinguistic predicate" and distinguishes the following cases:

- "John called" is true.

- "It is true that John called."

The first case belongs to the metalanguage whereas the second is more likely to belong to the object language. Hence, "it is true that" possesses the logical status of a redundancy. "Is true", on the other hand, is a predicate necessary for making general observations such as "John was telling the truth about Phillip."

Upon this basis, along with that of the logical content of assertions (where logical content is inversely proportional to probability), Popper went on to develop his important notion of verisimilitude or "truthlikeness". The intuitive idea behind verisimilitude is that the assertions or hypotheses of scientific theories can be objectively measured with respect to the amount of truth and falsity that they imply. And, in this way, one theory can be evaluated as more or less true than another on a quantitative basis which, Popper emphasises forcefully, has nothing to do with "subjective probabilities" or other merely "epistemic" considerations.

The simplest mathematical formulation that Popper gives of this concept can be found in the tenth chapter of Conjectures and Refutations. Here he defines it as:

where is the verisimilitude of a, is a measure of the content of the truth of a, and is a measure of the content of the falsity of a.

Popper's original attempt to define not just verisimilitude, but an actual measure of it, turned out to be inadequate. However, it inspired a wealth of new attempts.[13]

Popper's three worlds[edit]

Knowledge, for Popper, was objective, both in the sense that it is objectively true (or truthlike), and also in the sense that knowledge has an ontological status (i.e., knowledge as object) independent of the knowing subject (Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach, 1972). He proposed three worlds:[54] World One, being the physical world, or physical states; World Two, being the world of mind, or mental states, ideas, and perceptions; and World Three, being the body of human knowledge expressed in its manifold forms, or the products of the second world made manifest in the materials of the first world (i.e., books, papers, paintings, symphonies, and all the products of the human mind). World Three, he argued, was the product of individual human beings in exactly the same sense that an animal path is the product of individual animals, and that, as such, has an existence and evolution independent of any individual knowing subjects. The influence of World Three, in his view, on the individual human mind (World Two) is at least as strong as the influence of World One. In other words, the knowledge held by a given individual mind owes at least as much to the total accumulated wealth of human knowledge, made manifest, as to the world of direct experience. As such, the growth of human knowledge could be said to be a function of the independent evolution of World Three. Many contemporary philosophers, such as Daniel Dennett, have not embraced Popper's Three World conjecture, due mostly, it seems, to its resemblance to mind-body dualism.

Origin and evolution of life[edit]

This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (January 2018) |

The creation–evolution controversy in the United States raises the issue of whether creationistic ideas may be legitimately called science and whether evolution itself may be legitimately called science. In the debate, both sides and even courts in their decisions have frequently invoked Popper's criterion of falsifiability (see Daubert standard). In this context, passages written by Popper are frequently quoted in which he speaks about such issues himself. For example, he famously stated "Darwinism is not a testable scientific theory, but a metaphysical research program—a possible framework for testable scientific theories." He continued:

And yet, the theory is invaluable. I do not see how, without it, our knowledge could have grown as it has done since Darwin. In trying to explain experiments with bacteria which become adapted to, say, penicillin, it is quite clear that we are greatly helped by the theory of natural selection. Although it is metaphysical, it sheds much light upon very concrete and very practical researches. It allows us to study adaptation to a new environment (such as a penicillin-infested environment) in a rational way: it suggests the existence of a mechanism of adaptation, and it allows us even to study in detail the mechanism at work.[55]

He also noted that theism, presented as explaining adaptation, "was worse than an open admission of failure, for it created the impression that an ultimate explanation had been reached".[56]

Popper later said:

When speaking here of Darwinism, I shall speak always of today's theory—that is Darwin's own theory of natural selection supported by the Mendelian theory of heredity, by the theory of the mutation and recombination of genes in a gene pool, and by the decoded genetic code. This is an immensely impressive and powerful theory. The claim that it completely explains evolution is of course a bold claim, and very far from being established. All scientific theories are conjectures, even those that have successfully passed many severe and varied tests. The Mendelian underpinning of modern Darwinism has been well tested, and so has the theory of evolution which says that all terrestrial life has evolved from a few primitive unicellular organisms, possibly even from one single organism.[56]

In 1974, regarding DNA and the origin of life he said:

What makes the origin of life and of the genetic code a disturbing riddle is this: the genetic code is without any biological function unless it is translated; that is, unless it leads to the synthesis of the proteins whose structure is laid down by the code. But, as Monod points out, the machinery by which the cell (at least the non-primitive cell, which is the only one we know) translates the code "consists of at least fifty macromolecular components which are themselves coded in the DNA". (Monod, 1970;[57] 1971, 143[58])

Thus the code can not be translated except by using certain products of its translation. This constitutes a really baffling circle; a vicious circle, it seems, for any attempt to form a model, or theory, of the genesis of the genetic code.Thus we may be faced with the possibility that the origin of life (like the origin of the universe) becomes an impenetrable barrier to science, and a residue to all attempts to reduce biology to chemistry and physics.[59]

He explained that the difficulty of testing had led some people to describe natural selection as a tautology, and that he too had in the past described the theory as "almost tautological", and had tried to explain how the theory could be untestable (as is a tautology) and yet of great scientific interest:

My solution was that the doctrine of natural selection is a most successful metaphysical research programme. It raises detailed problems in many fields, and it tells us what we would expect of an acceptable solution of these problems. I still believe that natural selection works in this way as a research programme. Nevertheless, I have changed my mind about the testability and logical status of the theory of natural selection; and I am glad to have an opportunity to make a recantation.[56]

Popper summarised his new view as follows:

The theory of natural selection may be so formulated that it is far from tautological. In this case it is not only testable, but it turns out to be not strictly universally true. There seem to be exceptions, as with so many biological theories; and considering the random character of the variations on which natural selection operates, the occurrence of exceptions is not surprising. Thus not all phenomena of evolution are explained by natural selection alone. Yet in every particular case it is a challenging research program to show how far natural selection can possibly be held responsible for the evolution of a particular organ or behavioural program.[60]

These frequently quoted passages are only a very small part of what Popper wrote on the issue of evolution, however, and give the wrong impression that he mainly discussed questions of its falsifiability. Popper never invented this criterion to give justifiable use of words like science. In fact, Popper stresses at the beginning of Logic of Scientific Discovery that "the last thing I wish to do, however, is to advocate another dogma"[61] and that "what is to be called a 'science' and who is to be called a 'scientist' must always remain a matter of convention or decision."[62] He quotes Menger's dictum that "Definitions are dogmas; only the conclusions drawn from them can afford us any new insight"[63] and notes that different definitions of science can be rationally debated and compared:

I do not try to justify [the aims of science which I have in mind], however, by representing them as the true or the essential aims of science. This would only distort the issue, and it would mean a relapse into positivist dogmatism. There is only one way, as far as I can see, of arguing rationally in support of my proposals. This is to analyse their logical consequences: to point out their fertility—their power to elucidate the problems of the theory of knowledge.[64]

Popper had his own sophisticated views on evolution[65] that go much beyond what the frequently-quoted passages say.[66] In effect, Popper agreed with some of the points of both creationists and naturalists, but also disagreed with both views on crucial aspects. Popper understood the universe as a creative entity that invents new things, including life, but without the necessity of something like a god, especially not one who is pulling strings from behind the curtain. He said that evolution of the genotype must, as the creationists say, work in a goal-directed way[67] but disagreed with their view that it must necessarily be the hand of god that imposes these goals onto the stage of life.

Instead, he formulated the spearhead model of evolution, a version of genetic pluralism. According to this model, living organisms themselves have goals, and act according to these goals, each guided by a central control. In its most sophisticated form, this is the brain of humans, but controls also exist in much less sophisticated ways for species of lower complexity, such as the amoeba. This control organ plays a special role in evolution—it is the "spearhead of evolution". The goals bring the purpose into the world. Mutations in the genes that determine the structure of the control may then cause drastic changes in behaviour, preferences and goals, without having an impact on the organism's phenotype. Popper postulates that such purely behavioural changes are less likely to be lethal for the organism compared to drastic changes of the phenotype.[68]

Popper contrasts his views with the notion of the "hopeful monster" that has large phenotype mutations and calls it the "hopeful behavioural monster". After behaviour has changed radically, small but quick changes of the phenotype follow to make the organism fitter to its changed goals. This way it looks as if the phenotype were changing guided by some invisible hand, while it is merely natural selection working in combination with the new behaviour. For example, according to this hypothesis, the eating habits of the giraffe must have changed before its elongated neck evolved. Popper contrasted this view as "evolution from within" or "active Darwinism" (the organism actively trying to discover new ways of life and being on a quest for conquering new ecological niches),[69][70] with the naturalistic "evolution from without" (which has the picture of a hostile environment only trying to kill the mostly passive organism, or perhaps segregate some of its groups).

Popper was a key figure encouraging patent lawyer Günter Wächtershäuser to publish his Iron–sulfur world hypothesis on abiogenesis and his criticism of "soup" theory.

About the creation-evolution controversy itself, Popper initially wrote that he considered it "a somewhat sensational clash between a brilliant scientific hypothesis concerning the history of the various species of animals and plants on earth, and an older metaphysical theory which, incidentally, happened to be part of an established religious belief" with a footnote to the effect that he "agree[s] with Professor C.E. Raven when, in his Science, Religion, and the Future, 1943, he calls this conflict 'a storm in a Victorian tea-cup'; though the force of this remark is perhaps a little impaired by the attention he pays to the vapours still emerging from the cup—to the Great Systems of Evolutionist Philosophy, produced by Bergson, Whitehead, Smuts, and others."[71] In his later work, however, when he had developed his own "spearhead model" and "active Darwinism" theories, Popper revised this view and found some validity in the controversy:

I have to confess that this cup of tea has become, after all, my cup of tea; and with it I have to eat humble pie.[72]

Free will[edit]

Popper and John Eccles speculated on the problem of free will for many years, generally agreeing on an interactionist dualist theory of mind. However, although Popper was a body-mind dualist, he did not think that the mind is a substance separate from the body: he thought that mental or psychological properties or aspects of people are distinct from physical ones.[73]

When he gave the second Arthur Holly Compton Memorial Lecture in 1965, Popper revisited the idea of quantum indeterminacy as a source of human freedom. Eccles had suggested that "critically poised neurons" might be influenced by the mind to assist in a decision. Popper criticised Compton's idea of amplified quantum events affecting the decision. He wrote:

The idea that the only alternative to determinism is just sheer chance was taken over by Schlick, together with many of his views on the subject, from Hume, who asserted that "the removal" of what he called "physical necessity" must always result in "the same thing with chance. As objects must either be conjoin'd or not,... 'tis impossible to admit of any medium betwixt chance and an absolute necessity".

I shall later argue against this important doctrine according to which the alternative to determinism is sheer chance. Yet I must admit that the doctrine seems to hold good for the quantum-theoretical models which have been designed to explain, or at least to illustrate, the possibility of human freedom. This seems to be the reason why these models are so very unsatisfactory.[74]

Hume's and Schlick's ontological thesis that there cannot exist anything intermediate between chance and determinism seems to me not only highly dogmatic (not to say doctrinaire) but clearly absurd; and it is understandable only on the assumption that they believed in a complete determinism in which chance has no status except as a symptom of our ignorance.[75]

Popper called not for something between chance and necessity but for a combination of randomness and control to explain freedom, though not yet explicitly in two stages with random chance before the controlled decision, saying, "freedom is not just chance but, rather, the result of a subtle interplay between something almost random or haphazard, and something like a restrictive or selective control."[76]

Then in his 1977 book with John Eccles, The Self and its Brain, Popper finally formulates the two-stage model in a temporal sequence. And he compares free will to Darwinian evolution and natural selection:

New ideas have a striking similarity to genetic mutations. Now, let us look for a moment at genetic mutations. Mutations are, it seems, brought about by quantum theoretical indeterminacy (including radiation effects). Accordingly, they are also probabilistic and not in themselves originally selected or adequate, but on them there subsequently operates natural selection which eliminates inappropriate mutations. Now we could conceive of a similar process with respect to new ideas and to free-will decisions, and similar things.

That is to say, a range of possibilities is brought about by a probabilistic and quantum mechanically characterised set of proposals, as it were—of possibilities brought forward by the brain. On these there then operates a kind of selective procedure which eliminates those proposals and those possibilities which are not acceptable to the mind.[77]

Religion and God[edit]

In an interview[31] that Popper gave in 1969 with the condition that it should be kept secret until after his death, he summarised his position on God as follows: "I don't know whether God exists or not. ... Some forms of atheism are arrogant and ignorant and should be rejected, but agnosticism—to admit that we don't know and to search—is all right. ... When I look at what I call the gift of life, I feel a gratitude which is in tune with some religious ideas of God. However, the moment I even speak of it, I am embarrassed that I may do something wrong to God in talking about God." He objected to organised religion, saying "it tends to use the name of God in vain", noting the danger of fanaticism because of religious conflicts: "The whole thing goes back to myths which, though they may have a kernel of truth, are untrue. Why then should the Jewish myth be true and the Indian and Egyptian myths not be true?" In a letter unrelated to the interview, he stressed his tolerant attitude: "Although I am not for religion, I do think that we should show respect for anybody who believes honestly."[9][78][79]

Influence[edit]

Popper helped to establish the philosophy of science as an autonomous discipline within philosophy, through his own prolific and influential works, and also through his influence on his own contemporaries and students. Popper founded in 1946 the Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method at the London School of Economics and there lectured and influenced both Imre Lakatos and Paul Feyerabend, two of the foremost philosophers of science in the next generation of philosophy of science. (Lakatos significantly modified Popper's position,[80]:1 and Feyerabend repudiated it entirely, but the work of both is deeply influenced by Popper and engaged with many of the problems that Popper set.)

While there is some dispute as to the matter of influence, Popper had a long-standing and close friendship with economist Friedrich Hayek, who was also brought to the London School of Economics from Vienna. Each found support and similarities in the other's work, citing each other often, though not without qualification. In a letter to Hayek in 1944, Popper stated, "I think I have learnt more from you than from any other living thinker, except perhaps Alfred Tarski."[81] Popper dedicated his Conjectures and Refutations to Hayek. For his part, Hayek dedicated a collection of papers, Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, to Popper, and in 1982 said, "...ever since his Logik der Forschung first came out in 1934, I have been a complete adherent to his general theory of methodology."[82]

Popper also had long and mutually influential friendships with art historian Ernst Gombrich, biologist Peter Medawar, and neuroscientist John Carew Eccles. The German jurist Reinhold Zippelius uses Popper's method of "trial and error" in his legal philosophy.[83]

Popper's influence, both through his work in philosophy of science and through his political philosophy, has also extended beyond the academy. One of Popper's students at the London School of Economics was George Soros, who later became a billionaire investor, and among whose philanthropic foundations is the Open Society Institute, a think-tank named in honour of Popper's The Open Society and Its Enemies.[84]

Criticism[edit]

Most criticisms of Popper's philosophy are of the falsification, or error elimination, element in his account of problem solving. Popper presents falsifiability as both an ideal and as an important principle in a practical method of effective human problem solving; as such, the current conclusions of science are stronger than pseudo-sciences or non-sciences, insofar as they have survived this particularly vigorous selection method.[citation needed]

He does not argue that any such conclusions are therefore true, or that this describes the actual methods of any particular scientist. Rather, it is recommended as an essential principle of methodology that, if enacted by a system or community, will lead to slow but steady progress of a sort (relative to how well the system or community enacts the method). It has been suggested that Popper's ideas are often mistaken for a hard logical account of truth because of the historical co-incidence of their appearing at the same time as logical positivism, the followers of which mistook his aims for their own.[85]

The Quine-Duhem thesis argues that it's impossible to test a single hypothesis on its own, since each one comes as part of an environment of theories. Thus we can only say that the whole package of relevant theories has been collectively falsified, but cannot conclusively say which element of the package must be replaced. An example of this is given by the discovery of the planet Neptune: when the motion of Uranus was found not to match the predictions of Newton's laws, the theory "There are seven planets in the solar system" was rejected, and not Newton's laws themselves. Popper discussed this critique of naïve falsificationism in Chapters 3 and 4 of The Logic of Scientific Discovery. For Popper, theories are accepted or rejected via a sort of selection process. Theories that say more about the way things appear are to be preferred over those that do not; the more generally applicable a theory is, the greater its value. Thus Newton's laws, with their wide general application, are to be preferred over the much more specific "the solar system has seven planets".[dubious ]

The philosopher Thomas Kuhn writes in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) that he places an emphasis on anomalous experiences similar to that Popper places on falsification. However, he adds that anomalous experiences cannot be identified with falsification, and questions whether theories could be falsified in the manner suggested by Popper.[86] Kuhn argues in The Essential Tension (1977) that while Popper was correct that psychoanalysis cannot be considered a science, there are better reasons for drawing that conclusion than those Popper provided.[87] Popper's student Imre Lakatos attempted to reconcile Kuhn's work with falsificationism by arguing that science progresses by the falsification of research programs rather than the more specific universal statements of naïve falsificationism.[citation needed] Another of Popper's students Paul Feyerabend ultimately rejected any prescriptive methodology, and argued that the only universal method characterising scientific progress was anything goes.[citation needed]

Popper claimed to have recognised already in the 1934 version of his Logic of Discovery a fact later stressed by Kuhn, "that scientists necessarily develop their ideas within a definite theoretical framework", and to that extent to have anticipated Kuhn's central point about "normal science".[88] (But Popper criticised what he saw as Kuhn's relativism.[89]) Also, in his collection Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge (Harper & Row, 1963), Popper writes, "Science must begin with myths, and with the criticism of myths; neither with the collection of observations, nor with the invention of experiments, but with the critical discussion of myths, and of magical techniques and practices. The scientific tradition is distinguished from the pre-scientific tradition in having two layers. Like the latter, it passes on its theories; but it also passes on a critical attitude towards them. The theories are passed on, not as dogmas, but rather with the challenge to discuss them and improve upon them."

Another objection is that it is not always possible to demonstrate falsehood definitively, especially if one is using statistical criteria to evaluate a null hypothesis. More generally it is not always clear, if evidence contradicts a hypothesis, that this is a sign of flaws in the hypothesis rather than of flaws in the evidence. However, this is a misunderstanding of what Popper's philosophy of science sets out to do. Rather than offering a set of instructions that merely need to be followed diligently to achieve science, Popper makes it clear in The Logic of Scientific Discovery that his belief is that the resolution of conflicts between hypotheses and observations can only be a matter of the collective judgment of scientists, in each individual case.[90]

In Science Versus Crime, Houck writes[91] that Popper's falsificationism can be questioned logically: it is not clear how Popper would deal with a statement like "for every metal, there is a temperature at which it will melt." The hypothesis cannot be falsified by any possible observation, for there will always be a higher temperature than tested at which the metal may in fact melt, yet it seems to be a valid scientific hypothesis. These examples were pointed out by Carl Gustav Hempel. Hempel came to acknowledge that Logical Positivism's verificationism was untenable, but argued that falsificationism was equally untenable on logical grounds alone. The simplest response to this is that, because Popper describes how theories attain, maintain and lose scientific status, individual consequences of currently accepted scientific theories are scientific in the sense of being part of tentative scientific knowledge, and both of Hempel's examples fall under this category. For instance, atomic theory implies that all metals melt at some temperature.

An early adversary of Popper's critical rationalism, Karl-Otto Apel attempted a comprehensive refutation of Popper's philosophy. In Transformation der Philosophie (1973), Apel charged Popper with being guilty of, amongst other things, a pragmatic contradiction.[92]

The philosopher Adolf Grünbaum argues in The Foundations of Psychoanalysis (1984) that Popper's view that psychoanalytic theories, even in principle, cannot be falsified is incorrect.[93] The philosopher Roger Scruton argues in Sexual Desire (1986) that Popper was mistaken to claim that Freudian theory implies no testable observation and therefore does not have genuine predictive power. Scruton maintains that Freudian theory has both "theoretical terms" and "empirical content." He points to the example of Freud's theory of repression, which in his view has "strong empirical content" and implies testable consequences. Nevertheless, Scruton also concluded that Freudian theory is not genuinely scientific.[94] Charles Taylor accuses Popper of exploiting his worldwide fame as an epistemologist to diminish the importance of philosophers of the 20th-century continental tradition. According to Taylor, Popper's criticisms are completely baseless, but they are received with an attention and respect that Popper's "intrinsic worth hardly merits".[95]

The philosopher John Gray writes in Straw Dogs (2003) that Popper's account of scientific method would have prevented the theories of Charles Darwin and Albert Einstein from being accepted.[96]

The philosopher and psychologist Michel ter Hark writes in Popper, Otto Selz and the rise of evolutionary epistemology (2004) that Popper took some of his ideas from his tutor, the German psychologist Otto Selz. Selz never published his ideas, partly because of the rise of Nazism, which forced him to quit his work in 1933, and the prohibition of referring to Selz' work. Popper, the historian of ideas and his scholarship, is criticised in some academic quarters for his rejection of Plato, Hegel and Marx.[97]

Bibliography[edit]

- The Two Fundamental Problems of the Theory of Knowledge, 1930–33 (as a typescript circulating as Die beiden Grundprobleme der Erkenntnistheorie; as a German book 1979, as English translation 2008), ISBN 0-415-39431-7

- The Logic of Scientific Discovery, 1934 (as Logik der Forschung, English translation 1959), ISBN 0-415-27844-9

- The Poverty of Historicism, 1936 (private reading at a meeting in Brussels, 1944/45 as a series of journal articles in Econometrica, 1957 a book), ISBN 0-415-06569-0

- The Open Society and Its Enemies, 1945 Vol 1 ISBN 0-415-29063-5, Vol 2 ISBN 0-415-29063-5

- Quantum Theory and the Schism in Physics, 1956/57 (as privately circulated galley proofs; published as a book 1982), ISBN 0-415-09112-8

- The Open Universe: An Argument for Indeterminism, 1956/57 (as privately circulated galley proofs; published as a book 1982), ISBN 0-415-07865-2

- Realism and the Aim of Science, 1956/57 (as privately circulated galley proofs; published as a book 1983), ISBN 0-09-151450-9

- Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge, 1963, ISBN 0-415-04318-2

- Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach, 1972, Rev. ed., 1979, ISBN 0-19-875024-2

- Unended Quest: An Intellectual Autobiography, 2002 [1976]. ISBN 0-415-28589-5 (ISBN 0-415-28590-9)

- The Self and Its Brain: An Argument for Interactionism (with Sir John C. Eccles), 1977, ISBN 0-415-05898-8

- In Search of a Better World, 1984, ISBN 0-415-13548-6

- Die Zukunft ist offen (The Future is Open) (with Konrad Lorenz), 1985 (in German), ISBN 3-492-00640-X

- A World of Propensities, 1990, ISBN 1-85506-000-0

- The Lesson of this Century, (Interviewer: Giancarlo Bosetti, English translation: Patrick Camiller), 1992, ISBN 0-415-12958-3

- All Life is Problem Solving, 1994, ISBN 0-415-24992-9

- The Myth of the Framework: In Defence of Science and Rationality (edited by Mark Amadeus Notturno) 1994. ISBN 0-415-13555-9

- Knowledge and the Mind-Body Problem: In Defence of Interaction (edited by Mark Amadeus Notturno) 1994 ISBN 0-415-11504-3

- The World of Parmenides, Essays on the Presocratic Enlightenment, 1998, (Edited by Arne F. Petersen with the assistance of Jørgen Mejer), ISBN 0-415-17301-9

- After The Open Society, 2008. (Edited by Jeremy Shearmur and Piers Norris Turner, this volume contains a large number of Popper's previously unpublished or uncollected writings on political and social themes.) ISBN 978-0-415-30908-0

- Frühe Schriften, 2006 (Edited by Troels Eggers Hansen, includes Popper's writings and publications from before the Logic, including his previously unpublished thesis, dissertation and journal articles published that relate to the Wiener Schulreform) ISBN 978-3-16-147632-7

Filmography[edit]

- Interview Karl Popper, Open Universiteit, 1988.

See also[edit]

- Calculus of predispositions

- Contributions to liberal theory

- Critique of psychoanalysis

- Evolutionary epistemology

- Liberalism in Austria

- Popper legend

- Positivism dispute

- Predispositioning theory

- Poper Scientific Stand up

References[edit]

- ^ "Karl Popper and Critical Rationalism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ a b Thornton, Stephen (1 January 2015). Zalta, Edward N., ed. Karl Popper (Winter 2015 ed.). "Popper professes to be anti-conventionalist, and his commitment to the correspondence theory of truth places him firmly within the realist's camp".

- ^ a b c "Karl Popper: Political Philosophy". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ "Cartesianism (philosophy): Contemporary influences" in Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

- ^ Hacohen, Malachi Haim (2000). Karl Popper – The Formative Years, 1902–1945: Politics and Philosophy in Interwar Vienna. Cambridge University Press. pp. 83–85.

- ^ Thomas S. Kuhn (1970). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press (2nd ed.). p. 146.

- ^ Michael Redhead (1996). From Physics to Metaphysics. Cambridge University Press. p. 15.

- ^ Roger Penrose (1994). Shadows of the Mind. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c d e Miller, D. (1997). "Sir Karl Raimund Popper, C. H., F. B. A. 28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994.: Elected F.R.S. 1976". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 43: 369–409. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1997.0021.

- ^ Watkins, J. (1996). "Obituary of Karl Popper, 1902–1994". Proceedings of the British Academy. 94: 645–684.

- ^ "Karl Popper (1902–94) advocated by Andrew Marr". BBC In Our Time – Greatest Philosopher. Retrieved January 2015.

- ^ Adams, I.; Dyson, R. W. (2007). Fifty Major Political Thinkers. Routledge. p. 196. "He became a British citizen in 1945".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Thornton, Stephen (2015-01-01). Zalta, Edward N., ed. Karl Popper (Winter 2015 ed.).

- ^ Horgan, J (1992). "Profile: Karl R. Popper – The Intellectual Warrior". Scientific American. 267 (5): 38–44. Bibcode:1992SciAm.267e..38H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1192-38.

- ^ "Karl Popper: Philosophy of Science". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ William W. Bartley (1964). "Rationality versus the Theory of Rationality". In Mario Bunge: The Critical Approach to Science and Philosophy (The Free Press of Glencoe). Section IX.

- ^ a b Malachi Haim Hacohen. Karl Popper – The Formative Years, 1902–1945: Politics and Philosophy in Interwar Vienna. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. pp. 10 & 23, ISBN 0-521-47053-6

- ^ Magee, Bryan. The Story of Philosophy. New York: DK Publishing, 2001. p. 221, ISBN 0-7894-3511-X

- ^ "Eichstätter Karl Popper-Seite". Helmut-zenz.de. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ^ Karl Popper: Kritischer Rationalismus und Verteidigung der offenen Gesellschaft. In Josef Rattner, Gerhard Danzer (Eds.): Europäisches Österreich: Literatur- und geistesgeschichtliche Essays über den Zeitraum 1800–1980, p. 293

- ^ Karl R. Popper ([1976] 2002. Unended Quest: An Intellectual Autobiography, p. 6.

- ^ Raphael, F. The Great Philosophers London: Phoenix, p. 447, ISBN 0-7538-1136-7

- ^ Manfred Lube: Karl R. Popper – Die Bibliothek des Philosophen als Spiegel seines Lebens. Imprimatur. Ein Jahrbuch für Bücherfreunde. Neue Folge Band 18 (2003), S. 207–38, ISBN 3-447-04723-2.

- ^ "Cf. Thomas Sturm: "Bühler and Popper: Kantian therapies for the crisis in psychology," in: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 43 (2012), pp. 462–72". Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ^ A. C. Ewing was responsible for Karl Popper's 1936 invitation to Cambridge (Edmonds and Eidinow 2001, p. 67).

- ^ "Sir Karl Popper Is Dead at 92. Philosopher of 'Open Society'". The New York Times. 18 September 1994. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

Sir Karl Popper, a philosopher who was a defender of democratic systems of government, died today in a hospital here. He was 92. He died of complications of cancer, pneumonia and kidney failure, said a manager at the hospital in this London suburb.

- ^ "Opensociety.de". Opensociety.de. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ "David Miller". Fs1.law.keio.ac.jp. 17 September 1994. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ^ Sir Karl Popper at Find a Grave

- ^ "The Karl Popper Charitable Trust". OpenCharities. 10 September 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ^ a b Edward Zerin: Karl Popper On God: The Lost Interview. Skeptic 6:2 (1998)

- ^ "The International Academy of Humanism". Secularhumanism.org. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ "London Gazette". 5 March 1965. p. 22. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "London Gazette". 12 June 1982. p. 5. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ País, Ediciones El (24 May 1989). "Karl Popper recoge hoy en Barcelona el Premi Internacional Catalunya". El País.

- ^ a b "Karl Raimund Popper". Inamori Foundation. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ Ian Charles Jarvie; Karl Milford; David W. Miller (2006). Karl Popper: A Centenary Assessment Volume I. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-0-7546-5375-2.

- ^ Malachi Haim Hacohen (4 March 2002). Karl Popper. The Formative Years. 1902–1945: Politics and Philosophy in Interwar Vienna. Cambridge University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-521-89055-7.

- ^ One of the severest critics of Popper's so-called demarcation thesis was Adolf Grünbaum, cf. Is Falsifiability the Touchstone of Scientific Rationality? (1976), and The Degeneration of Popper's Theory of Demarcation (1989), both in his Collected Works (edited by Thomas Kupka), vol. I, New York: Oxford University Press 2013, ch. 1 (pp. 9–42) & ch. 2 (pp. 43–61).

- ^ Popper, Karl Raimond (1994). The myth of the framework: in defence of science and rationality. Editor:Mark Amadeus Notturno. Routledge. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9781135974800.

- ^ De Bruin, Boudewijn. "Popper's Conception of the Rationality Principle in the Social Sciences". Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ Popper, Karl Raimund (1946) Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume XX.

- ^ Gregory, Frank Hutson (1996) Arithmetic and Reality: A Development of Popper's Ideas. City University of Hong Kong. Republished in Philosophy of Mathematics Education Journal No. 26 (December 2011).

- ^ The Poverty of Historicism, p. 21

- ^ Hacohen, Malachi Haim (2002-03-04). Karl Popper - the Formative Years, 1902-1945: Politics and Philosophy in Interwar Vienna. p. 82. ISBN 9780521890557. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ Popper, Karl (15 April 2013). All Life is Problem Solving. ISBN 9781135973056. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ Popper, Karl R. ([1976] 2002). Unended Quest: An Intellectual Autobiography, pp. 32 -37

- ^ Daniel Stedman Jones (2014), Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics, p. 40: "Popper argued that some socialists ought to be invited to participate."

- ^ The Open Society and Its Enemies: The Spell of Plato by Karl Raimund Popper, Volume 1, 1947, George Routledge & sons, ltd., p. 226, Notes to chapter 7: https://archive.org/details/opensocietyandit033120mbp,

- ^ The Open Society and Its Enemies: The Spell of Plato, by Karl Raimund Popper, Princeton University Press, 1971, ISBN 0-691-01968-1, p. 265

- ^ The Open Society And Its Enemies, Complete: Volumes I and II, Karl R. Popper, 1962, Fifth edition (revised), 1966, (PDF)

- ^ The Open Society and Its Enemies, p. 581

- ^ Williams, Liz (2012-09-10). "Karl Popper, the enemy of certainty, part 1: a rejection of empiricism". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ Karl Popper, Three Worlds, The Tanner Lecture on Human Values, The University of Michigan, 1978.

- ^ Unended Quest ch. 37 – see Bibliography

- ^ a b c "CA211.1: Popper on natural selection's testability". talk.origins. 2 November 2005. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ^ Le Hasard et la Nécessité. Editions du Seuil, Paris.

- ^ Chance and Necessity. Knopf, New York

- ^ Ayala, Francisco; Ayala, Francisco José; Ayala, Francisco Jose; Dobzhansky, Theodosius (1974). Studies in the Philosophy of Biology: Reduction and Related Problems. ISBN 9780520026490. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Radnitzky, Gerard; Popper, Karl Raimund (1987). Evolutionary Epistemology, Rationality, and the Sociology of Knowledge. ISBN 9780812690392. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ LScD, preface to the first english edition

- ^ LScD, section 10

- ^ LScD, section 11

- ^ LScD, section 4

- ^ Niemann, Hans-Joachim: Karl Popper and the Two New Secrets of Life: Including Karl Popper's Medawar Lecture 1986 and Three Related Texts. Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014. ISBN 978-3161532078.

- ^ For a secondary source see H. Keuth: The philosophy of Karl Popper, section 15.3 "World 3 and emergent evolution". See also John Watkins: Popper and Darwinism. The Power of Argumentation (Ed Enrique Suárez Iñiguez). Primary sources are, in particular,

- Objective Knowledge: An evolutionary approach, section "Evolution and the Tree of Knowledge";

- Evolutionary epistemology (Eds. G. Radnitzsky, W.W. Bartley), section "Natural selection and the emergence of mind";

- In search of a better world, section "Knowledge and the shaping of rationality: the search for a better world", p. 16;

- Knowledge and the Body-Mind Problem: In Defence of Interaction, section "World 3 and emergent evolution";

- A world of propensities, section "Towards an evolutionary theory of knowledge"; and

- The Self and Its Brain: An Argument for Interactionism (with John C. Eccles), sections "The biological approach to human knowledge and intelligence" and "The biological function of conscious and intelligent activity".

- ^ D. W. Miller: Karl Popper, a scientific memoir. Out of Error, p. 33

- ^ K. Popper: Objective Knowledge, section "Evolution and the Tree of Knowledge", subsection "Addendum. The Hopeful Behavioural Monster" (p. 281)

- ^ "Philosophical confusion? – Science Frontiers". Science-frontiers.com. 2 October 1986. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ Michel Ter Hark: Popper, Otto Selz and the Rise Of Evolutionary Epistemology, pp. 184 ff

- ^ Karl R. Popper, The Poverty of Historicism, p. 97

- ^ Section XVIII, chapter "Of Clouds and Clocks" of Objective Knowledge.

- ^ Popper, K. R. "Of Clouds and Clocks," in his Objective Knowledge, corrected edition, pp. 206–55, Oxford, Oxford University Press (1973), p. 231 footnote 43, & p. 252; also Popper, K. R. "Natural Selection and the Emergence of Mind", 1977.

- ^ Popper, K. R. "Of Clouds and Clocks," in: Objective Knowledge, corrected edition, p. 227, Oxford, Oxford University Press (1973). Popper's Hume quote is from Treatise on Human Understanding, (see note 8) Book I, Part I, Section XIV, p. 171

- ^ Of Clouds and Clocks, in Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach, Oxford (1972) pp. 227 ff.

- ^ ibid, p. 232

- ^ Eccles, John C. and Karl Popper. The Self and Its Brain: An Argument for Interactionism, Routledge (1984)

- ^ Popper archives fasc. 297.11

- ^ See also Karl Popper: On freedom. All life is problem solving (1999), chapter 7, pp. 81 ff

- ^ Kadvany, John (2001). Imre Lakatos and the Guises of Reason. Duke University Press Books. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-8223-2660-1. Retrieved 22 January 2016.Site on Lakatos/Popper John Kadvany, PhD

- ^ Hacohen, 2000

- ^ Weimer and Palermo, 1982

- ^ Reinhold Zippelius, Die experimentierende Methode im Recht, 1991 (ISBN 3-515-05901-6), and Rechtsphilosophie, 6th ed., 2011 (ISBN 978-3-406-61191-9)

- ^ Soros, George (2006). The Age of Fallibility. NY: Public Affairs. pp. 16–18.

- ^ Bryan Magee 1973: Popper (Modern Masters series)

- ^ Kuhn, Thomas (2012). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 50th Anniversary Edition. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. pp. 145–146.

- ^ Kuhn, Thomas S. (1977). The Essential Tension: Studies in Scientific Tradition and Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 274.

- ^ K R Popper (1970), "Normal Science and its Dangers", pp. 51–58 in I Lakatos & A Musgrave (eds.) (1970), at p. 51.

- ^ K R Popper (1970), in I Lakatos & A Musgrave (eds.) (1970), at p. 56.

- ^ Popper, Karl, (1934) Logik der Forschung, Springer. Vienna. Amplified English edition, Popper (1959), ISBN 0-415-27844-9

- ^ Houck, Max M., Science Versus Crime, Infobase Publishing, 2009, p. 65

- ^ See: "Apel, Karl-Otto," La philosophie de A a Z, by Elizabeth Clement, Chantal Demonque, Laurence Hansen-Love, and Pierre Kahn, Paris, 1994, Hatier, 19–20. See Also: Towards a Transformation of Philosophy (Marquette Studies in Philosophy, No 20), by Karl-Otto Apel, trans., Glyn Adey and David Fisby, Milwaukee, 1998, Marquette University Press.

- ^ Grünbaum, Adolf (1984). The Foundations of Psychoanalysis: A Philosophical Critique. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 103–112.

- ^ Scruton, Roger (1994). Sexual Desire: A Philosophical Investigation. London: Phoenix. p. 201.

- ^ Taylor, Charles, "Overcoming Epistemology", in Philosophical Arguments, Harvard University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-674-66477-9

- ^ Gray, John (2002). Straw Dogs. Granta Books, London. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-86207-512-2.

- ^ See: "Popper is committing a serious historical error in attributing the organic theory of the state to Plato and accusing him of all the fallacies of post-Hegelian and Marxist historicism—the theory that history is controlled by the inexorable laws governing the behavior of superindividual social entities of which human beings and their free choices are merely subordinate manifestations." Plato's Modern Enemies and the Theory of Natural Law, by John Wild, Chicago, 1964, The University of Chicago Press, 23. See Also: "In spite of the high rating one must accord his initial intention of fairness, his hatred for the enemies of the 'open society,' his zeal to destroy whatever seems to him destructive of the welfare of mankind, has led him into the extensive use of what may be called terminological counterpropaganda ..." and "With a few exceptions in Popper's favor, however, it is noticeable that reviewers possessed of special competence in particular fields—and here Lindsay is again to be included—have objected to Popper's conclusions in those very fields ..." and "Social scientists and social philosophers have deplored his radical denial of historical causation, together with his espousal of Hayek's systematic distrust of larger programs of social reform; historical students of philosophy have protested his violent polemical handling of Plato, Aristotle, and particularly Hegel; ethicists have found contradictions in the ethical theory ('critical dualism') upon which his polemic is largely based." In Defense of Plato, by Ronald B. Levinson, New York, 1970, Russell and Russell, 20.

Further reading[edit]

- Lube, Manfred. Karl R. Popper. Bibliographie 1925–2004. Wissenschaftstheorie, Sozialphilosophie, Logik, Wahrscheinlichkeitstheorie, Naturwissenschaften. Frankfurt/Main etc.: Peter Lang, 2005. 576 pp. (Schriftenreihe der Karl Popper Foundation Klagenfurt.3.) (Current edition)

- Gattei, Stefano. Karl Popper's Philosophy of Science. 2009.

- Miller, David. Critical Rationalism: A Restatement and Defence. 1994.

- David Miller (Ed.). Popper Selections.

- Watkins, John W. N.. Science and Scepticism. Preface & Contents. Princeton 1984 (Princeton University Press). ISBN 978-0-09-158010-0

- Jarvie, Ian Charles, Karl Milford, David W. Miller, ed. (2006). Karl Popper: A Centenary Assessment, Ashgate.

- Volume I: Life and Times, and Values in a World of Facts. Description & Contents.

- Volume II: Metaphysics and Epistemology Description & Contents.

- Volume III: Science. Description & Contents.

- Bailey, Richard, Education in the Open Society: Karl Popper and Schooling. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate 2000. The only book-length examination of Popper's relevance to education.

- Bartley, William Warren III. Unfathomed Knowledge, Unmeasured Wealth. La Salle, IL: Open Court Press 1990. A look at Popper and his influence by one of his students.

- Berkson, William K., and Wettersten, John. Learning from Error: Karl Popper's Psychology of Learning. La Salle, IL: Open Court 1984

- Cornforth, Maurice. (1977): The open philosophy and the open society, 2., (rev.) ed., Lawrence & Wishart, London. ISBN 0-85315-384-1. The fundamental critique from the Marxist standpoint.

- Edmonds, D., Eidinow, J. Wittgenstein's Poker. New York: Ecco 2001. A review of the origin of the conflict between Popper and Ludwig Wittgenstein, focused on events leading up to their volatile first encounter at 1946 Cambridge meeting.

- Feyerabend, Paul Against Method. London: New Left Books, 1975. A polemical, iconoclastic book by a former colleague of Popper's. Vigorously critical of Popper's rationalist view of science.

- Hacohen, M. Karl Popper: The Formative Years, 1902–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Hickey, J. Thomas. History of the Twentieth-Century Philosophy of Science Book V, Karl Popper And Falsificationist Criticism. www.philsci.com . 1995

- Kadvany, John Imre Lakatos and the Guises of Reason. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8223-2659-0. Explains how Imre Lakatos developed Popper's philosophy into a historicist and critical theory of scientific method.

- Keuth, Herbert. The Philosophy of Karl Popper. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. An accurate scholarly overview of Popper's philosophy, ideal for students.

- Kuhn, Thomas S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962. Central to contemporary philosophy of science is the debate between the followers of Kuhn and Popper on the nature of scientific enquiry. This is the book in which Kuhn's views received their classical statement.

- Lakatos, I & Musgrave, A (eds.) (1970), Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, Cambridge (Cambridge University Press). ISBN 0-521-07826-1

- Levinson, Paul, ed. In Pursuit of Truth: Essays on the Philosophy of Karl Popper on the Occasion of his 80th Birthday. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press, 1982. ISBN 0-391-02609-7 A collection of essays on Popper's thought and legacy by a wide range of his followers. With forewords by Isaac Asimov and Helmut Schmidt. Includes an interview with Sir Ernst Gombrich.

- Lindh, Allan Goddard (11 November 1993). "Did Popper solve Hume's problem?". Nature. 366 (6451): 105–06. Bibcode:1993Natur.366..105G. doi:10.1038/366105a0.

- Magee, Bryan. Popper. London: Fontana, 1977. An elegant introductory text. Very readable, albeit rather uncritical of its subject, by a former Member of Parliament.

- Magee, Bryan. Confessions of a Philosopher, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1997. Magee's philosophical autobiography, with a chapter on his relations with Popper. More critical of Popper than in the previous reference.

- Maxwell, Nicholas, Karl Popper, Science and Enlightenment, London, UCL Press, 2017. An exposition and development of Popper's philosophy of science and social philosophy, available free online.

- Munz, Peter. Beyond Wittgenstein's Poker: New Light on Popper and Wittgenstein Aldershot, Hampshire, UK: Ashgate, 2004. ISBN 0-7546-4016-7. Written by the only living student of both Wittgenstein and Popper, an eyewitness to the famous "poker" incident described above (Edmunds & Eidinow). Attempts to synthesize and reconcile the differences between these two philosophers.

- Niemann, Hans-Joachim. Lexikon des Kritischen Rationalismus, (Encyclopaedia of Critical Raionalism), Tübingen (Mohr Siebeck) 2004, ISBN 3-16-148395-2. More than a thousand headwords about critical rationalism, the most important arguments of K.R. Popper and H. Albert, quotations of the original wording. Edition for students in 2006, ISBN 3-16-149158-0.

- Notturno, Mark Amadeus. "Objectivity, Rationality, and the Third Realm: Justification and the Grounds of Psychologism". Boston: Martinus Nijhoff, 1985.

- Notturno, Mark Amadeus. On Popper. Wadsworth Philosophers Series. 2003. A very comprehensive book on Popper's philosophy by an accomplished Popperian.

- Notturno, Mark Amadeus. "Science and the Open Society". New York: CEU Press, 2000.

- O'Hear, Anthony. Karl Popper. London: Routledge, 1980. A critical account of Popper's thought, viewed from the perspective of contemporary analytic philosophy.

- Parusniková, Zuzana & Robert S. Cohen (2009). Rethinking Popper. Description and contents. Springer.