Ramayana

| Ramayana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Information | |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Author | Valmiki |

| Language | Sanskrit |

| Verses | 24,000 |

Ramayana (/rɑːˈmɑːjənə/;[1] Sanskrit: रामायणम्, Rāmāyaṇam [raːˈmaːjəɳəm]) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India, the other being the Mahābhārata. Along with the Mahābhārata, it forms the Hindu Itihasa.

The epic, traditionally ascribed to the Hindu Valmiki, narrates the life of Rama, the legendary prince of the Kosala Kingdom. It follows his fourteen-year exile to the forest from the kingdom, by his father King Dasharatha, on request of his third wife Kaikeyi. His travels across forests in India with his wife Sita and brother Lakshmana, the kidnapping of his wife by Ravana, the great king of Lanka, resulting in a war with him, and Rama's eventual return to Ayodhya to be crowned king.

There have been many attempts to unravel the epic's historical growth and compositional layers; various recent scholars' estimates for the earliest stage of the text range from the 7th to 4th centuries BCE, with later stages extending up to the 3rd century CE.[2]

The Ramayana is one of the largest ancient epics in world literature. It consists of nearly 24,000 verses (mostly set in the Shloka meter), divided into seven Kandas and about 500 sargas (chapters). In Hindu tradition, it is considered to be the adi-kavya (first poem). It depicts the duties of relationships, portraying ideal characters like the ideal father, the ideal servant, the ideal brother, the ideal husband and the ideal king. Ramayana was an important influence on later Sanskrit poetry and Hindu life and culture. Like Mahabharata, Ramayana is not just a story: it presents the teachings of ancient Hindu sages in narrative allegory, interspersing philosophical and ethical elements. The characters Rama, Sita, Lakshmana, Bharata, Hanuman, Shatrughna, and Ravana are all fundamental to the cultural consciousness of India, Nepal, Sri Lanka and south-east Asian countries such as Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia and Indonesia.

There are many versions of Ramayana in Indian languages, besides Buddhist, Sikh and Jain adaptations. There are also Cambodian, Indonesian, Filipino, Thai, Lao, Burmese and Malaysian versions of the tale.

Contents

Etymology[edit]

The name Ramayana is a tatpuruṣa compound of the name Rāma.

Textual history and structure[edit]

According to Hindu tradition, and the Ramayana itself, the epic belongs to the genre of itihasa like Mahabharata. The definition of itihāsa is a narrative of past events (purāvṛtta) which includes teachings on the goals of human life. According to Hindu tradition, Ramayana takes place during a period of time known as Treta Yuga.[3]

In its extant form, Valmiki's Ramayana is an epic poem of some 24,000 verses. The text survives in several thousand partial and complete manuscripts, the oldest of which is a palm-leaf manuscript found in Nepal and dated to the 11th century CE. A Times of India report dated 18 December 2015 informs about the discovery of a 6th-century manuscript of the Ramayana at the Asiatic Society library, Kolkata.[4] The Ramayana text has several regional renderings, recensions and sub recensions. Textual scholar Robert P. Goldman differentiates two major regional revisions: the northern (n) and the southern (s). Scholar Romesh Chunder Dutt writes that "the Ramayana, like the Mahabharata, is a growth of centuries, but the main story is more distinctly the creation of one mind."

There has been discussion as to whether the first and the last volumes (bala kandam and uttara kandam) of Valmiki's Ramayana were composed by the original author. Most Hindus still believe they are integral parts of the book, in spite of some style differences and narrative contradictions between these two volumes and the rest of the book.[5]

Retellings include Kamban's Ramavataram in Tamil (c. 11th–12th century), Gona Budda Reddy's Ramayanam in Telugu (c. 13th century), Madhava Kandali's Saptakanda Ramayana in Assamese (c. 14th century), Krittibas Ojha's Krittivasi Ramayan (also known as Shri Rama Panchali) in Bengali (c. 15th century), Sarala Das' Vilanka Ramayana (c. 15th century)[6][7][8][9] and Balaram Das' Dandi Ramayana (also known as the Jagamohan Ramayana) (c. 16th century) both in Odia, sant Eknath's Bhavarth Ramayan (c. 16th century) in Marathi, Tulsidas' Ramcharitamanas (c. 16th century) in Awadhi (which is an eastern form of Hindi) and Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan's Adhyathmaramayanam in Malayalam.

Period[edit]

Ramayana predates Mahabharata. However, the general cultural background of Ramayana is one of the post-urbanization periods of the eastern part of north India and Nepal, while Mahabharata reflects the Kuru areas west of this, from the Rigvedic to the late Vedic period.

By tradition, the text belongs to the Treta Yuga, second of the four eons (yuga) of Hindu chronology. Rama is said to have been born in the Treta yuga to king Dasharatha in the Ikshvaku dynasty.

The names of the characters (Rama, Sita, Dasharatha, Janaka, Vashista, Vishwamitra) are all known in late Vedic literature. However, nowhere in the surviving Vedic poetry is there a story similar to the Ramayana of Valmiki. According to the modern academic view, Vishnu, who, according to Bala Kanda, was incarnated as Rama, first came into prominence with the epics themselves and further, during the puranic period of the later 1st millennium CE. Also, in the epic Mahabharata, there is a version of Ramayana known as Ramopakhyana. This version is depicted as a narration to Yudhishthira.

Books two to six form the oldest portion of the epic, while the first and last books (Bala Kanda and Uttara Kanda, respectively) are later additions, as some style differences and narrative contradictions between these two volumes and the rest of the book.[5] The author or authors of Bala Kanda and Ayodhya Kanda appear to be familiar with the eastern Gangetic basin region of northern India and with the Kosala, Mithila and Magadha regions during the period of the sixteen Mahajanapadas, based on the fact that the geographical and geopolitical data accords with what is known about the region.

Characters[edit]

Ikshvaku dynasty[edit]

- Dasharatha is king of Ayodhya and father of Rama. He has three queens, Kausalya, Kaikeyi and Sumitra, and four sons: Bharata, and twins Lakshmana,Shatrughna and Rama. Once, Kaikeyi saved Dasaratha in a war and as a reward, she got the privilege from Dasaratha to fulfil two of her wishes at any time of her lifetime. She made use of the opportunity and forced Dasharatha to make their son Bharata crown prince and send Rama into exile for 14 years. Dasharatha dies heartbroken after Rama goes into exile.

- Rama is the main character of the tale. Portrayed as the seventh avatar of god Vishnu, he is the eldest and favourite son of Dasharatha, the king of Ayodhya and his Chief Queen, Kausalya. He is portrayed as the epitome of virtue. Dasharatha is forced by Kaikeyi to command Rama to relinquish his right to the throne for fourteen years and go into exile. Rama kills the evil demon Ravana, who abducted his wife Sita, and later returns to Ayodhya to form an ideal state.

- Sita is another of the tale's protagonists. She is a daughter of Mother Earth, adopted by King Janaka, and Rama's beloved wife. Rama went to Mithila and got a chance to marry her by breaking the Shiv Dhanush (bow) while trying to tie a knot to it in a competition organized by King Janaka of Mithila. The competition was to find the most suitable husband for Sita and many princes from different states competed to win her. Sita is the avatara of goddess Lakshmi, the consort of Vishnu. Sita is portrayed as the epitome of female purity and virtue. She follows her husband into exile and is abducted by the demon king Ravana. She is imprisoned on the island of Lanka, until Rama rescues her by defeating Ravana. Later, she gives birth to twin boys Luv and Kusha.

- Bharata is the son of Dasharatha and Queen Kaikeyi. When he learns that his mother Kaikeyi has forced Rama into exile and caused Dasharatha to die brokenhearted, he storms out of the palace and goes in search of Rama in the forest. When Rama refuses to return from his exile to assume the throne, Bharata obtains Rama's sandals and places them on the throne as a gesture that Rama is the true king. Bharata then rules Ayodhya as the regent of Rama for the next fourteen years, staying outside the city of Ayodhya. He was married to Mandavi.

- Lakshmana is a younger brother of Rama, who chose to go into exile with him. He is the son of King Dasharatha and Queen Sumitra and twin of Shatrughna. Lakshmana is portrayed as an avatar of Shesha, the nāga associated with the god Vishnu. He spends his time protecting Sita and Rama, during which time he fights the demoness Shurpanakha. He is forced to leave Sita, who was deceived by the demon Maricha into believing that Rama was in trouble. Sita is abducted by Ravana upon his leaving her. He was married to Sita's younger sister Urmila.

- Shatrughna is a son of Dasharatha and his third wife Queen Sumitra. He is the youngest brother of Rama and also the twin brother of Lakshmana. He was married to Shrutakirti.

Allies of Rama[edit]

- Hanuman is a vanara belonging to the kingdom of Kishkindha. He is an ideal bhakta of Rama. He is born as son of Kesari, a Vanara king in Sumeru region and his wife Añjanā. He plays an important part in locating Sita and in the ensuing battle. He is believed to live until our modern world.

- Sugriva, a vanara king who helped Rama regain Sita from Ravana. He had an agreement with Rama through which Vali – Sugriva's brother and king of Kishkindha – would be killed by Rama in exchange for Sugriva's help in finding Sita. Sugriva ultimately ascends the throne of Kishkindha after the slaying of Vali and fulfills his promise by putting the Vanara forces at Rama's disposal.

- Angada is a vanara who helped Rama find his wife Sita and fight her abductor, Ravana, in Ramayana. He was son of Vali and Tara and nephew of Sugriva. Angada and Tara are instrumental in reconciling Rama and his brother, Lakshmana, with Sugriva after Sugriva fails to fulfill his promise to help Rama find and rescue his wife. Together they are able to convince Sugriva to honour his pledge to Rama instead of spending his time carousing and drinking.

- Riksha

- Jambavan/Jamvanta is known as Riksharaj (King of the Rikshas). Rikshas are bears. In the epic Ramayana, Jambavantha helped Rama find his wife Sita and fight her abductor, Ravana. It is he who makes Hanuman realize his immense capabilities and encourages him to fly across the ocean to search for Sita in Lanka.

- Griddha

- Jatayu, son of Aruṇa and nephew of Garuda. A demi-god who has the form of a vulture that tries to rescue Sita from Ravana. Jatayu fought valiantly with Ravana, but as Jatayu was very old, Ravana soon got the better of him. As Rama and Lakshmana chanced upon the stricken and dying Jatayu in their search for Sita, he informs them of the direction in which Ravana had gone.

- Sampati, son of Aruna, brother of Jatayu. Sampati's role proved to be instrumental in the search for Sita.

- Vibhishana, youngest brother of Ravana. He was against the abduction of Sita and joined the forces of Rama when Ravana refused to return her. His intricate knowledge of Lanka was vital in the war and he was crowned king after the fall of Ravana.

Foes Of Rama[edit]

- Ravana, a rakshasa, is the king of Lanka. He was son of a sage named Vishrava and daitya princess Kaikesi. After performing severe penance for ten thousand years he received a boon from the creator-god Brahma: he could henceforth not be killed by gods, demons, or spirits. He is portrayed as a powerful demon king who disturbs the penances of rishis. Vishnu incarnates as the human Rama to defeat him, thus circumventing the boon given by Brahma.

- Indrajit or Meghnadha, the eldest son of Ravana who twice defeated Rama and Lakshmana in battle, before succumbing to Lakshmana. An adept of the magical arts, he coupled his supreme fighting skills with various stratagems to inflict heavy losses on Vanara army before his death.

- Kumbhakarna, brother of Ravana, famous for his eating and sleeping. He would sleep for months at a time and would be extremely ravenous upon waking up, consuming anything set before him. His monstrous size and loyalty made him an important part of Ravana's army. During the war he decimated the Vanara army before Rama cut off his limbs and head.

- Shurpanakha, Ravana's demoness sister who fell in love with Rama and had the magical power to take any form she wanted.

- Vali, was king of Kishkindha, husband of Tara, a son of Indra, elder brother of Sugriva and father of Angada. Vali was famous for the boon that he had received, according to which anyone who fought him in single-combat lost half his strength to Vali, thereby making Vali invulnerable to any enemy. He was killed by Lord Rama, an Avatar of Vishnu.

Synopsis[edit]

Bala Kanda[edit]

Dasharatha was the king of Ayodhya. He had three wives: Kaushalya, Kaikeyi and Sumitra. He was childless for a long time and anxious to produce an heir, so he performs a fire sacrifice known as putra-kameshti yagya. As a consequence, Rama is first born to Kaushalya, Bharata is born to Kaikeyi, Lakshmana and Shatrughna are born to Sumitra. These sons are endowed, to various degrees, with the essence of the Supreme Trinity Entity Vishnu; Vishnu had opted to be born into mortality to combat the demon Ravana, who was oppressing the gods, and who could only be destroyed by a mortal. The boys are reared as the princes of the realm, receiving instructions from the scriptures and in warfare from Vashistha. When Rama is 16 years old, sage Vishwamitra comes to the court of Dasharatha in search of help against demons who were disturbing sacrificial rites. He chooses Rama, who is followed by Lakshmana, his constant companion throughout the story. Rama and Lakshmana receive instructions and supernatural weapons from Vishwamitra and proceed to destroy the demons.

Janaka was the king of Mithila. One day, a female child was found in the field by the king in the deep furrow dug by his plough. Overwhelmed with joy, the king regarded the child as a "miraculous gift of god". The child was named Sita, the Sanskrit word for furrow. Sita grew up to be a girl of unparalleled beauty and charm. The king had decided that who ever could lift and wield the heavy bow, presented to his ancestors by Shiva, could marry Sita. Sage Vishwamitra takes Rama and Lakshmana to Mithila to show the bow. Then Rama desires to lift it and goes on to wield the bow and when he draws the string, it breaks.[10] Marriages are arranged between the sons of Dasharatha and daughters of Janaka. Rama gets married to Sita, Lakshmana to Urmila, Bharata to Mandavi and Shatrughna to Shrutakirti. The weddings are celebrated with great festivity in Mithila and the marriage party returns to Ayodhya.

Ayodhya Kanda[edit]

After Rama and Sita have been married for twelve years, an elderly Dasharatha expresses his desire to crown Rama, to which the Kosala assembly and his subjects express their support. On the eve of the great event, Kaikeyi – her jealousy aroused by Manthara, a wicked maidservant – claims two boons that Dasharatha had long ago granted her. Kaikeyi demands Rama to be exiled into the wilderness for fourteen years, while the succession passes to her son Bharata. The heartbroken king, constrained by his rigid devotion to his given word, accedes to Kaikeyi's demands. Rama accepts his father's reluctant decree with absolute submission and calm self-control which characterises him throughout the story. He is joined by Sita and Lakshmana. When he asks Sita not to follow him, she says, "the forest where you dwell is Ayodhya for me and Ayodhya without you is a veritable hell for me." After Rama's departure, King Dasharatha, unable to bear the grief, passes away. Meanwhile, Bharata who was on a visit to his maternal uncle, learns about the events in Ayodhya. Bharata refuses to profit from his mother's wicked scheming and visits Rama in the forest. He requests Rama to return and rule. But Rama, determined to carry out his father's orders to the letter, refuses to return before the period of exile. However, Bharata carries Rama's sandals and keeps them on the throne, while he rules as Rama's regent.[citation needed]

Aranya Kanda[edit]

After thirteen years of exile, Rama, Sita and Lakshmana journey southward along the banks of river Godavari, where they build cottages and live off the land. At the Panchavati forest they are visited by a rakshasi named Shurpanakha, sister of Ravana. She tries to seduce the brothers and, after failing, attempts to kill Sita. Lakshmana stops her by cutting off her nose and ears. Hearing of this, her brother Khara organises an attack against the princes. Rama defeats Khara and his raskshasas.

When the news of these events reach Ravana, he resolves to destroy Rama by capturing Sita with the aid of the rakshasa Maricha. Maricha, assuming the form of a golden deer, captivates Sita's attention. Entranced by the beauty of the deer, Sita pleads with Rama to capture it. Rama, aware that this is the ploy of the demons, cannot dissuade Sita from her desire and chases the deer into the forest, leaving Sita under Lakshmana's guard. After some time, Sita hears Rama calling out to her; afraid for his life, she insists that Lakshmana rush to his aid. Lakshmana tries to assure her that Rama is invincible and that it is best if he continues to follow Rama's orders to protect her. On the verge of hysterics, Sita insists that it is not she but Rama who needs Lakshmana's help. He obeys her wish but stipulates that she is not to leave the cottage or entertain any stranger. He draws a chalk outline, the Lakshmana rekha, around the cottage and casts a spell on it that prevents anyone from entering the boundary but allows people to exit. With the coast finally clear, Ravana appears in the guise of an ascetic requesting Sita's hospitality. Unaware of her guest's plan, Sita is tricked into leaving the rekha and is then forcibly carried away by Ravana.[11]

Jatayu, a vulture, tries to rescue Sita, but is mortally wounded. At Lanka, Sita is kept under the guard of rakshasis. Ravana asks Sita to marry him, but she refuses, being eternally devoted to Rama. Meanwhile, Rama and Lakshmana learn about Sita's abduction from Jatayu and immediately set out to save her. During their search, they meet Kabandha and the ascetic Shabari, who direct them towards Sugriva and Hanuman.

Kishkindha Kanda[edit]

Kishkindha Kanda is set in the ape (Vanara) citadel Kishkindha. Rama and Lakshmana meet Hanuman, the biggest devotee of Rama, greatest of ape heroes and an adherent of Sugriva, the banished pretender to the throne of Kishkindha. Rama befriends Sugriva and helps him by killing his elder brother Vali thus regaining the kingdom of Kishkindha, in exchange for helping Rama to recover Sita. However Sugriva soon forgets his promise and spends his time in enjoying his powers. The clever former ape queen Tara (wife of Vali) calmly intervenes to prevent an enraged Lakshmana from destroying the ape citadel. She then eloquently convinces Sugriva to honour his pledge. Sugriva then sends search parties to the four corners of the earth, only to return without success from north, east and west. The southern search party under the leadership of Angada and Hanuman learns from a vulture named Sampati (elder brother of Jatayu), that Sita was taken to Lanka.

Sundara Kanda[edit]

Sundara Kanda forms the heart of Valmiki's Ramayana and consists of a detailed, vivid account of Hanuman's adventures. After learning about Sita, Hanuman assumes a gargantuan form and makes a colossal leap across the sea to Lanka. On the way he meets with many challenges like facing a Gandharva kanya who comes in the form of a demon to test his abilities. He encounters a mountain named Mainakudu who offers Lord Hanuman assistance and offers him rest. Lord Hanuman refuses because there is little time remaining to complete the search for Sita.

After entering into Lanka, he finds a demon, Lankini, who protects all of Lanka. Hanuman fights with her and subjugates her in order to get into Lanka. In the process Lankini, who had an earlier vision/warning from the gods that the end of Lanka nears if someone defeats Lankini. Here, Hanuman explores the demons' kingdom and spies on Ravana. He locates Sita in Ashoka grove, where she is being wooed and threatened by Ravana and his rakshasis to marry Ravana. Hanuman reassures Sita, giving Rama's signet ring as a sign of good faith. He offers to carry Sita back to Rama; however, she refuses and says that it is not the dharma, stating that Ramayana will not have significance if Hanuman carries her to Rama – "When Rama is not there Ravana carried Sita forcibly and when Ravana was not there, Hanuman carried Sita back to Rama". She says that Rama himself must come and avenge the insult of her abduction.

Hanuman then wreaks havoc in Lanka by destroying trees and buildings and killing Ravana's warriors. He allows himself to be captured and delivered to Ravana. He gives a bold lecture to Ravana to release Sita. He is condemned and his tail is set on fire, but he escapes his bonds and leaping from roof to roof, sets fire to Ravana's citadel and makes the giant leap back from the island. The joyous search party returns to Kishkindha with the news.

Yuddha Kanda[edit]

Also known as Lanka Kanda, this book describes the war between the army of Rama and the army of Ravana. Having received Hanuman's report on Sita, Rama and Lakshmana proceed with their allies towards the shore of the southern sea. There they are joined by Ravana's renegade brother Vibhishana. The apes named Nala and Nila construct a floating bridge (known as Rama Setu)[12] across the sea, using stones that floated on water because they had Rama's name written on them. The princes and their army cross over to Lanka. A lengthy war ensues. During a battle, Ravana's son Indrajit hurls a powerful weapon at Lakshmana, who is badly wounded and is nearly killed.[citation needed] So Hanuman assumes a gigantic form and flies from Lanka to the Himalayas. Upon reaching Mount Sumeru, Hanuman was unable to identify the herb that could cure Lakshmana and so decided to bring the entire mountain back to Lanka. Eventually, the war ends when Rama kills Ravana. Rama then installs Vibhishana on the throne of Lanka.

On meeting Sita, Rama asks her to undergo an Agni Pariksha (test of fire) to prove her chastity, as he wants to get rid of the rumors surrounding her purity. When Sita plunges into the sacrificial fire, Agni, lord of fire raises Sita, unharmed, to the throne, attesting to her innocence. The episode of Agni Pariksha varies in the versions of Ramayana by Valmiki and Tulsidas. In Tulsidas's Ramacharitamanas, Sita was under the protection of Agni (see Maya Sita) so it was necessary to bring her out before reuniting with Rama. At the expiration of his term of exile, Rama returns to Ayodhya with Sita and Lakshmana, where the coronation is performed. This is the beginning of Ram Rajya, which implies an ideal state with good morals. Ramayan is not only the story about how truth defeats the evil, it also teaches us to forget all the evil and arrogance that resides inside ourselves.[13]

Uttara Kanda[edit]

_LACMA_AC1999.127.45.jpg/220px-Hermitage_of_Valmiki%2C_Folio_from_the_%22Nadaun%22_Ramayana_(Adventures_of_Rama)_LACMA_AC1999.127.45.jpg)

Uttara Kanda concerns the final years of Rama, Sita and Rama's brothers. After being crowned king, Rama passes time pleasantly with Sita. After some time, Sita gets pregnant with twin children. However, despite Agni Pariksha ("fire ordeal") of Sita, rumours about her "purity" are spreading among the populace of Ayodhya. Rama yields to public opinion and reluctantly banishes Sita to the forest, where the sage Valmiki provides shelter in his ashrama ("hermitage"). Here, she gives birth to twin boys, Lava and Kusha, who become pupils of Valmiki and are brought up in ignorance of their identity.

Valmiki composes the Ramayana and teaches Lava and Kusha to sing it. Later, Rama holds a ceremony during the Ashwamedha yagna, which sage Valmiki, with Lava and Kusha, attends. Lava and Kusha sing the Ramayana in the presence of Rama and his vast audience. When Lava and Kusha recite about Sita's exile, Rama becomes grief-stricken and Valmiki produces Sita. Sita calls upon the Earth, her mother, to receive her and as the ground opens, she vanishes into it. Rama then learns that Lava and Kusha are his children. Many years later, a messenger from the Gods appears and informs Rama that the mission of his incarnation is over. Rama returns to his celestial abode along with his brothers. It was dramatised as Uttararamacarita by the Sanskrit poet Bhavabhuti.

Versions[edit]

As in many oral epics, multiple versions of the Ramayana survive. In particular, the Ramayana related in north India differs in important respects from that preserved in south India and the rest of southeast Asia. There is an extensive tradition of oral storytelling based on Ramayana in Indonesia, Cambodia, Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Laos, Vietnam and Maldives.

India[edit]

There are diverse regional versions of the Ramayana written by various authors in India. Some of them differ significantly from each other. During the 12th century, Kamban wrote Ramavataram, known popularly as Kambaramayanam in Tamil. A Telugu version, Ranganatha Ramayanam, was written by Gona Budda Reddy in the 14th century. The earliest translation to a regional Indo-Aryan language is the early 14th century Saptakanda Ramayana in Assamese by Madhava Kandali. Valmiki's Ramayana inspired Sri Ramacharit Manas by Tulsidas in 1576, an epic Awadhi (a dialect of Hindi) version with a slant more grounded in a different realm of Hindu literature, that of bhakti; it is an acknowledged masterpiece of India, popularly known as Tulsi-krita Ramayana. Gujarati poet Premanand wrote a version of the Ramayana in the 17th century. Other versions include Krittivasi Ramayan, a Bengali version by Krittibas Ojha in the 15th century; Vilanka Ramayana by 15th century poet Sarala Dasa[14] and Dandi Ramayana (also known as Jagamohana Ramayana) by 16th century poet Balarama Dasa, both in Odia; a Torave Ramayana in Kannada by 16th-century poet Narahari; Adhyathmaramayanam, a Malayalam version by Thunchaththu Ramanujan Ezhuthachan in the 16th century; in Marathi by Sridhara in the 18th century; in Maithili by Chanda Jha in the 19th century; and in the 20th century, Rashtrakavi Kuvempu's Sri Ramayana Darshanam in Kannada.

There is a sub-plot to the Ramayana, prevalent in some parts of India, relating the adventures of Ahiravan and Mahi Ravana, evil brother of Ravana, which enhances the role of Hanuman in the story. Hanuman rescues Rama and Lakshmana after they are kidnapped by the Ahi-Mahi Ravana at the behest of Ravana and held prisoner in a subterranean cave, to be sacrificed to the goddess Kali. Adbhuta Ramayana is a version that is obscure but also attributed to Valmiki – intended as a supplementary to the original Valmiki Ramayana. In this variant of the narrative, Sita is accorded far more prominence, such as elaboration of the events surrounding her birth – in this case to Ravana's wife, Mandodari as well as her conquest of Ravana's older brother in her Mahakali form.

Buddhist version[edit]

In the Buddhist variant of the Ramayana (Dasarathajātaka, #467), Dasharatha was king of Benares and not Ayodhya. Rama (called Rāmapaṇḍita in this version) was the son of Kaushalya, first wife of Dasharatha. Lakṣmaṇa (Lakkhaṇa) was a sibling of Rama and son of Sumitra, the second wife of Dasharatha. Sita was the wife of Rama. To protect his children from his wife Kaikeyi, who wished to promote her son Bharata, Dasharatha sent the three to a hermitage in the Himalayas for a twelve-year exile. After nine years, Dasharatha died and Lakkhaṇa and Sita returned; Rāmapaṇḍita, in deference to his father's wishes, remained in exile for a further two years. This version does not include the abduction of Sītā.There is no Ravan in this version i.e. no Ram-ravan war.

In the explanatory commentary on Jātaka, Rāmapaṇḍita is said to have been a previous incarnation of the Buddha, and Sita an incarnation of Yasodharā.

But, Ravana appears in other Buddhist literature, the Lankavatara Sutra.

Jain version[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (August 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Jain versions of the Ramayana can be found in the various Jain agamas like Ravisena's Padmapurana (story of Padmaja and Rama, Padmaja being the name of Sita), Hemacandra's Trisastisalakapurusa charitra (hagiography of 63 illustrious persons), Sanghadasa's Vasudevahindi and Uttarapurana by Gunabhadara. According to Jain cosmology, every half time cycle has nine sets of Balarama, Vasudeva and prativasudeva. Rama, Lakshmana and Ravana are the eighth baladeva, vasudeva and prativasudeva respectively. Padmanabh Jaini notes that, unlike in the Hindu puranas, the names Baladeva and Vasudeva are not restricted to Balarama and Krishna in Jain Puranas. Instead they serve as names of two distinct classes of mighty brothers, who appear nine times in each half time cycle and jointly rule half the earth as half-chakravartins. Jaini traces the origin of this list of brothers to the jinacharitra (lives of jinas) by Acharya Bhadrabahu (3d–4th century BCE).

In the Jain epic of Ramayana, it is not Rama who kills Ravana as told in the Hindu version. Perhaps this is because Rama, a liberated Jain Soul in his last life, is unwilling to kill.[15] Instead, it is Lakshmana who kills Ravana.[15] In the end, Rama, who led an upright life, renounces his kingdom, becomes a Jain monk and attains moksha. On the other hand, Lakshmana and Ravana go to Hell. However, it is predicted that ultimately they both will be reborn as upright persons and attain liberation in their future births. According to Jain texts, Ravana will be the future Tirthankara (omniscient teacher) of Jainism.

The Jain versions have some variations from Valmiki's Ramayana. Dasharatha, the king of Saketa had four queens: Aparajita, Sumitra, Suprabha and Kaikeyi. These four queens had four sons. Aparajita's son was Padma and he became known by the name of Rama. Sumitra's son was Narayana: he came to be known by another name, Lakshmana. Kaikeyi's son was Bharata and Suprabha's son was Shatrughna. Furthermore, not much was thought of Rama's fidelity to Sita. According to the Jain version, Rama had four chief queens: Maithili, Prabhavati, Ratinibha, and Sridama. Furthermore, Sita takes renunciation as a Jain ascetic after Rama abandons her and is reborn in heaven. Rama, after Lakshmana's death, also renounces his kingdom and becomes a Jain monk. Ultimately, he attains Kevala Jnana omniscience and finally liberation. Rama predicts that Ravana and Lakshmana, who were in the fourth hell, will attain liberation in their future births. Accordingly, Ravana is the future tirthankara of the next half ascending time cycle and Sita will be his Ganadhara.

Sikh version[edit]

In Guru Granth Sahib, there is a description of two types of Ramayana. One is a spiritual Ramayana which is the actual subject of Guru Granth Sahib, in which Ravana is ego, Sita is budhi (intellect), Rama is inner soul and Laxman is mann (attention, mind). Guru Granth Sahib also believes in the existence of Dashavatara who were kings of their times which tried their best to restore order to the world. King Rama (Ramchandra) was one of those who is not covered in Guru Granth Sahib. Guru Granth Sahib states:

- ਹੁਕਮਿ ਉਪਾਏ ਦਸ ਅਉਤਾਰਾ॥

- हुकमि उपाए दस अउतारा॥

- By hukam (supreme command), he created his ten incarnations

This version of the Ramayana was written by Guru Gobind Singh, which is part of Dasam Granth.

He also said that the almighty, invisible, all prevailing God created great numbers of Indras, Moons and Suns, Deities, Demons and sages, and also numerous saints and Brahmanas (enlightened people). But they too were caught in the noose of death (Kaal) (transmigration of the soul). This is similar to the explanation in Bhagavad Gita which is part of the Mahabharata.[citation needed]

Nepal[edit]

Besides being the site of discovery of the oldest surviving manuscript of the Ramayana, Nepal gave rise to two regional variants in mid 19th – early 20th century. One, written by Bhanubhakta Acharya, is considered the first epic of Nepali language, while the other, written by Siddhidas Mahaju in Nepal Bhasa was a foundational influence in the Nepal Bhasa renaissance.

Ramayana written by Bhanubhakta Acharya is one of the most popular verses in Nepal. The popularization of the Ramayana and its tale, originally written in Sanskrit Language was greatly enhanced by the work of Bhanubhakta. Mainly because of his writing of Nepali Ramayana, Bhanubhakta is also called Aadi Kavi or The Pioneering Poet.

Southeast Asian[edit]

Cambodia[edit]

The Cambodian version of the Ramayana, Reamker (Khmer: រាមកេរ្ដិ៍ - Glory of Rama), is the most famous story of Khmer literature since the Kingdom of Funan era. It adapts the Hindu concepts to Buddhist themes and shows the balance of good and evil in the world. The Reamker has several differences from the original Ramayana, including scenes not included in the original and emphasis on Hanuman and Sovanna Maccha, a retelling which influences the Thai and Lao versions. Reamker in Cambodia is not confined to the realm of literature but extends to all Cambodian art forms, such as sculpture, Khmer classical dance, theatre known as lakhorn luang (the foundation of the royal ballet), poetry and the mural and bas-reliefs seen at the Silver Pagoda and Angkor Wat.

Indonesia[edit]

There are several Indonesian adaptations of Ramayana, including the Javanese Kakawin Ramayana[16][17] and Balinese Ramakavaca.[18] The first half of Kakawin Ramayana is similar to the original Sanskrit version, while the latter half is very different. One of the recognizable modifications is the inclusion of the indigenous Javanese guardian demigod, Semar, and his sons, Gareng, Petruk, and Bagong who make up the numerically significant four Punokawan or "clown servants". Kakawin Ramayana is believed to have been written in Central Java circa 870 AD during the reign of Mpu Sindok in the Medang Kingdom.[19] The Javanese Kakawin Ramayana is not based on Valmiki's epic, which was then the most famous version of Rama's story, but based on Ravanavadha or the "Ravana massacre", which is the sixth or seventh century poem by Indian poet Bhattikavya.[20]

Kakawin Ramayana was further developed on the neighboring island of Bali becoming the Balinese Ramakavaca. The bas-reliefs of Ramayana and Krishnayana scenes are carved on balustrades of the 9th century Prambanan temple in Yogyakarta,[21] as well as in the 14th century Penataran temple in East Java.[22] In Indonesia, the Ramayana is a deeply ingrained aspect of the culture, especially among Javanese, Balinese and Sundanese people, and has become the source of moral and spiritual guidance as well as aesthetic expression and entertainment, for example in wayang and traditional dances.[23] The Balinese kecak dance for example, retells the story of the Ramayana, with dancers playing the roles of Rama, Sita, Lakhsmana, Jatayu, Hanuman, Ravana, Kumbhakarna and Indrajit surrounded by a troupe of over 50 bare-chested men who serve as the chorus chanting "cak". The performance also includes a fire show to describe the burning of Lanka by Hanuman.[24] In Yogyakarta, the Wayang Wong Javanese dance also retells the Ramayana. One example of a dance production of the Ramayana in Java is the Ramayana Ballet performed on the Trimurti Prambanan open air stage, with the three main prasad spires of the Prambanan Hindu temple as a backdrop.[25]

Laos[edit]

Phra Lak Phra Lam is a Lao language version, whose title comes from Lakshmana and Rama. The story of Lakshmana and Rama is told as the previous life of Gautama buddha.

Malaysia[edit]

The Hikayat Seri Rama of Malaysia incorporated element of both Hindu and Islamic mythology.[26][27][28]

Myanmar[edit]

Yama Zatdaw is the Burmese version of Ramayana. It is also considered the unofficial national epic of Myanmar. There are nine known pieces of the Yama Zatdaw in Myanmar. The Burmese name for the story itself is Yamayana, while zatdaw refers to the acted play or being part of the jataka tales of Theravada Buddhism. This Burmese version is also heavily influenced by Ramakien (Thai version of Ramayana) which resulted from various invasions by Konbaung Dynasty kings toward the Ayutthaya Kingdom.

Philippines[edit]

The Maharadia Lawana, an epic poem of the Maranao people of the Philippines, has been regarded as an indigenized version of the Ramayana since it was documented and translated into English by Professor Juan R. Francisco and Nagasura Madale in 1968.[29](p"264")[30] The poem, which had not been written down before Francisco and Madale's translation,[29](p"264") narrates the adventures of the monkey-king, Maharadia Lawana, whom the Gods have gifted with immortality.[29]

Francisco, an indologist from the University of the Philippines Manila, believed that the Ramayana narrative arrived in the Philippines some time between the 17th to 19th centuries, via interactions with Javanese and Malaysian cultures which traded extensively with India.[31](p101)

By the time it was documented in the 1960s, the character names, place names, and the precise episodes and events in Maharadia Lawana's narrative already had some notable differences from those of the Ramayana. Francisco believed that this was a sign of "indigenization", and suggested that some changes had already been introduced in Malaysia and Java even before the story was heard by the Maranao, and that upon reaching the Maranao homeland, the story was "further indigenized to suit Philippine cultural perspectives and orientations."[31](p"103")

Thailand[edit]

Thailand's popular national epic Ramakien (Thai:รามเกียรติ์., from Sanskrit rāmakīrti, glory of Rama) is derived from the Hindu epic. In Ramakien, Sita is the daughter of Ravana and Mandodari (thotsakan and montho). Vibhishana (phiphek), the astrologer brother of Ravana, predicts the death of Ravana from the horoscope of Sita. Ravana has thrown her into the water, but she is later rescued by Janaka (chanok).[15]:149 While the main story is identical to that of Ramayana, many other aspects were transposed into a Thai context, such as the clothes, weapons, topography and elements of nature, which are described as being Thai in style. It has an expanded role for Hanuman and he is portrayed as a lascivious character. Ramakien can be seen in an elaborate illustration at Wat Phra Kaew in Bangkok.

Critical edition[edit]

A critical edition of the text was compiled in India in the 1960s and 1970s, by the Oriental Institute at Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, India, utilizing dozens of manuscripts collected from across India and the surrounding region.[32] An English language translation of the critical edition was completed in November 2016 by Sanskrit scholar Robert P. Goldman of the University of California, Berkeley.[33]

Influence on culture and art[edit]

One of the most important literary works of ancient India, the Ramayana has had a profound impact on art and culture in the Indian subcontinent and southeast Asia with the lone exception of Vietnam. The story ushered in the tradition of the next thousand years of massive-scale works in the rich diction of regal courts and Hindu temples. It has also inspired much secondary literature in various languages, notably Kambaramayanam by Tamil poet Kambar of the 12th century, Telugu language Molla Ramayanam by poet Molla and Ranganatha Ramayanam by poet Gona Budda Reddy, 14th century Kannada poet Narahari's Torave Ramayana and 15th century Bengali poet Krittibas Ojha's Krittivasi Ramayan, as well as the 16th century Awadhi version, Ramacharitamanas, written by Tulsidas.

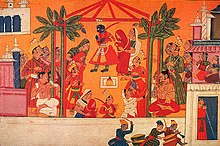

Ramayanic scenes have also been depicted through terracottas, stone sculptures, bronzes and paintings.[34] These include the stone panel at Nagarjunakonda in Andhra Pradesh depicting Bharata's meeting with Rama at Chitrakuta (3rd century CE).[34]

The Ramayana became popular in Southeast Asia during 8th century and was represented in literature, temple architecture, dance and theatre. Today, dramatic enactments of the story of the Ramayana, known as Ramlila, take place all across India and in many places across the globe within the Indian diaspora.

In Indonesia, especially Java and Bali, Ramayana has become a popular source of artistic expression for dance drama and shadow puppet performance in the region. Sendratari Ramayana is Javanese traditional ballet of wayang orang genre, routinely performed in Prambanan Trimurti temple and in cultural center of Yogyakarta.[35] Balinese dance drama of Ramayana is also performed routinely in Balinese Hindu temples, especially in temples such as Ubud and Uluwatu, where scenes from Ramayana is integrap part of kecak dance performance. Javanese wayang kulit purwa also draws its episodes from Ramayana or Mahabharata.

Ramayana has also been depicted in many paintings, most notably by the Malaysian artist Syed Thajudeen in 1972. The epic tale was picturized on canvas in epic proportions measuring 152 x 823 cm in 9 panels. The painting depicts three prolific parts of the epic, namely The Abduction of Sita, Hanuman visits Sita and Hanuman Burns Lanka. The painting is currently in the permanent collection of the Malaysian National Visual Arts Gallery.

Religious significance[edit]

Rama, the hero of the Ramayana, is one of the most popular deities worshipped in the Hindu religion. Each year, many devout pilgrims trace their journey through India and Nepal, halting at each of the holy sites along the way. The poem is not seen as just a literary monument, but serves as an integral part of Hinduism and is held in such reverence that the mere reading or hearing of it or certain passages of it, is believed by Hindus to free them from sin and bless the reader or listener.

According to Hindu tradition, Rama is an incarnation (Avatar) of god Vishnu. The main purpose of this incarnation is to demonstrate the righteous path (dharma) for all living creatures on earth.

In popular culture[edit]

Multiple modern, English-language adaptations of the epic exist, namely Ram Chandra Series by Amish Tripathi, Ramayana Series by Ashok Banker and a mythopoetic novel, Asura: Tale of the Vanquished by Anand Neelakantan. Another Indian author, Devdutt Pattanaik, has published three different retellings and commentaries of Ramayana titled Sita, The Book Of Ram and Hanuman's Ramayan. A number of plays, movies and television serials have also been produced based upon the Ramayana.

In Indonesia, "Ramayana" department store is named after the epic. The company which owns it is known as PT Ramayana Lestari Sentosa founded in 1978 with its main office located in Jakarta.

Stage[edit]

Starting in 1978 and under the supervision of Baba Hari Dass, Ramayana has been performed every year by Mount Madonna School in Watsonville, California. Currently, it is the largest yearly, Western version of the epic being performed. It takes the form of a colorful musical with custom costumes, sung and spoken dialog, jazz-rock orchestration and dance. This performance takes place in a large audience theater setting usually in June, in San Jose, CA. Dass has taught acting arts, costume-attire design, mask making and choreography to bring alive characters of Sri Ram, Sita, Hanuman, Lakshmana, Shiva, Parvati, Vibhishan, Jatayu, Sugriva, Surpanakha, Ravana and his rakshasa court, Meghnadha, Kumbhakarna and the army of monkeys and demons.

Movies[edit]

- Sampoorna Ramayanam – a Telugu/Tamil bilingual film starring N. T. Rama Rao (1958)

- Sampoorna Ramayana – a Hindi film directed by Babubhai Mistry (1961)

- Lava Kusha – a Uttara Kanda-based bilingual Telugu movie and Tamil movie starring N. T. Rama Rao (1963)

- Sampoorna Ramayanamu – a Telugu film directed by Bapu, starring Sobhan Babu, Chandrakala, S V Ranga Rao (1971)

- Kanchana Sita – a Malayalam film by G. Aravindan (1977)

- Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama – a Indo-Japanese traditional animation feature film (1992)

- A Little Princess (1995) – an American film chronicling the time of an orphaned child during WWI in an all-girl's boarding school. The story of Rama and Sita is told by the main character to the other girls and is constantly referenced throughout the plot.

- Opera Jawa – an Indonesian-Austrian film in the Indonesian language; inspired by the story of the abduction of Sita (2008)

- Sita Sings the Blues – an independent animated film (2008).

- Lava Kusa: The Warrior Twins – animated film based on Uttara Kanda (2010)

- Ramayana: The Epic – a Warner Bros. Indian animated film (2010)

- Sri Rama Rajyam – based on Uttara Kanda, a Telugu film starring Nandamuri Balakrishna (2011).

- Yak: The Giant King – a re-interpretation of Ramayana, the Thai animation film tells the story of a giant robot, Na Kiew, who is left wandering in a barren wasteland after a great war. Na Kiew meets Jao Phuek, a puny tin robot who has lost his memory and is now stuck with his new big friend. Together they set out across the desert populated by metal scavengers, to look for Ram, the creator of all robots. (2012).

- Mumbai Musical – DreamWorks Animation (2016)

Plays[edit]

- Kanchana Sita, Saketham and Lankalakshmi – award-winning trilogy by Malayalam playwright C. N. Sreekantan Nair

- Lankeswaran – a play by the award-winning Tamil cinema actor R. S. Manohar

- Kecak - a Balinese traditional folk dance which plays and tells the story of Ramayana

Exihibitions[edit]

- Gallery Nucleus:Ramayana Exhibition -Part of the art of the book Ramayana:Divine Loophole by Sanjay Patel.

- The Rama epic:Hero.Heroine,Ally,Foe by The Asian Art Museum.

Books[edit]

- "The Song of Rama" by Vanamali

- "Ramayana" by William Buck and S Triest

- "Ramayana:Divine Loophole" by Sanjay Patel

- "Sita: An Illustrate Retelling of the Ramayana" By Devdutt Pattanaik

- "Hanuman's Ramavan" By Devdutt Pattanaik

TV series[edit]

- Ramayan – originally broadcast on Doordarshan, produced by Ramanand Sagar in 1987

- Jai Hanuman – originally broadcast on Doordarshan, produced and directed by Sanjay Khan

- Ramayan (2002) – originally broadcast on Zee TV, produced by BR Films

- Ramayan (2008) – originally broadcast on Imagine TV, produced by Ramanand Sagar

- Ramayan (2012) – a remake of the 1987 series and aired on Zee TV

- Antariksh (2004) – a sci-fi version of Ramayan. Originally broadcast on Star Plus

- Raavan – series on life of Ravana based on Ramayana. Originally broadcast on Zee TV

- Sankatmochan Mahabali Hanuman – 2015 series based on the life of Hanuman presently broadcasting on Sony TV

- Siya Ke Ram – a series on Star Plus, originally broadcast from November 16, 2015 to November 4, 2016

Citations[edit]

- ^ "Ramayana". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ J. L. Brockington (1998). The Sanskrit Epics. BRILL. pp. 379–. ISBN 90-04-10260-4.

- ^ Ramayana By William Buck

- ^ Mukherjee Pandey, Jhimli (18 Dec 2015). "6th-century Ramayana found in Kolkata, stuns scholars". timesofindia.indiatimes.com. TNN. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ a b Uma Singh, Senu Singh (16 January 2013). "Ramayan as a complete life of real human" (PDF). Indian Journal of Arts. 1 (1): 2. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ Mukherjee, P. (1981). The History of Medieval Vaishnavism in Orissa. Asian Educational Services. p. 74. ISBN 9788120602298. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ Living Thoughts of the Ramayana. Jaico Publishing House. 2002. ISBN 9788179920022. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ Krishnamoorthy, K.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Sahitya Akademi (1991). A Critical Inventory of Rāmāyaṇa Studies in the World: Foreign languages. Sahitya Akademi in collaboration with Union Academique Internationale, Bruxelles. ISBN 9788172015077. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ Bulcke, C.; Prasāda, D. (2010). Rāmakathā and Other Essays. Vani Prakashan. p. 116. ISBN 9789350001073. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ CANTO LXVII.: THE BREAKING OF THE BOW. sacredtexts.com. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ Rajarajan, R.K.K. (2001) Sītāpaharaṇam: Changing thematic Idioms in Sanskrit and Tamil. In Dirk W. Lonne ed. Tofha-e-Dil: Festschrift Helmut Nespital, Reinbeck, 2 vols., pp. 783-97. ISBN 3-88587-033-9. https://www.academia.edu/2514821/S%C4%ABt%C4%81pahara%E1%B9%89am_Changing_thematic_Idioms_in_Sanskrit_and_Tamil

- ^ Rajarajan, R.K.K. (2014) Reflections on “Rāma-Setu” in South Asian Tradition. The Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society, Vol. 105.3: 1–14, ISSN 0047-8555. https://www.academia.edu/8779702/Reflections_on_R%C4%81ma-Setu_in_South_Asian_Tradition

- ^ "Shrimad Valmiki Ramayan | Hindi Books PDF". hindibookspdf.com. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (1 January 2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9780816075645.

- ^ a b c Ramanujan, A.K (2004). The Collected Essays of A.K. Ramanujan (PDF) (4. impr. ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 145.

- ^ "Ramayana Kakawin Vol. 1". archive.org.

- ^ "The Kakawin Ramayana -- an old Javanese rendering of the …". www.nas.gov.sg. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- ^ Bhalla, Prem P. (2017-08-22). ABC of Hinduism. Educreation Publishing. p. 277.

- ^ Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella, ed. The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ^ Ardianty, Dini (8 June 2015). "Perbedaan Ramayana - Mahabarata dalam Kesusastraan Jawa Kuna dan India" (in Indonesian).

- ^ "Prambanan - Taman Wisata Candi". borobudurpark.com. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- ^ Indonesia, Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia / National Library of. "Panataran Temple (East Java) - Temples of Indonesia". candi.pnri.go.id. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- ^ Joefe B. Santarita (2013), Revisiting Swarnabhumi/dvipa: Indian Influences in Ancient Southeast Asia

- ^ Planet, Lonely. "Bali Kecak Dance, Fire Dance and Sanghyang Dance Evening Tour in Indonesia". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- ^ "THE KEEPERS: CNN Introduces Guardians of Indonesia's Rich Cultural Traditions". www.indonesia.travel. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- ^ Fang, Liaw Yock (2013). A History of Classical Malay Literature. Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia. p. 142. ISBN 9789794618103.

- ^ Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 1898. pp. 107–.

- ^ Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 1898. pp. 143–.

- ^ a b c Guillermo, Artemio R. (2011-12-16). Historical Dictionary of the Philippines. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810875111.

- ^ Francisco, Juan R. "Maharadia Lawana" (PDF).

- ^ a b FRANCISCO, JUAN R. (1989). "The Indigenization of the Rama Story in the Philippines". Philippine Studies. 37 (1): 101–111. doi:10.2307/42633135. JSTOR 42633135.

- ^ "Ramayana Translation Project turns its last page, after four decades of research | Berkeley News". news.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ "UC Berkeley researchers complete decades-long translation project | The Daily Californian". dailycal.org. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ a b B. B. Lal (2008). Rāma, His Historicity, Mandir, and Setu: Evidence of Literature, Archaeology, and Other Sciences. Aryan Books. ISBN 978-81-7305-345-0.

- ^ Donald Frazier (11 February 2016). "On Java, a Creative Explosion in an Ancient City". The New York Times.

References[edit]

- Arya, Ravi Prakash (ed.).Ramayana of Valmiki: Sanskrit Text and English Translation. (English translation according to M. N. Dutt, introduction by Dr. Ramashraya Sharma, 4-volume set) Parimal Publications: Delhi, 1998, ISBN 81-7110-156-9

- Bhattacharji, Sukumari (1998). Legends of Devi. Orient Blackswan. p. 111. ISBN 978-81-250-1438-6.

- Brockington, John (2003). "The Sanskrit Epics". In Flood, Gavin. Blackwell companion to Hinduism. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 116–128. ISBN 0-631-21535-2.

- Buck, William; van Nooten, B. A. (2000). Ramayana. University of California Press. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-520-22703-3.

- Dutt, Romesh C. (2004). Ramayana. Kessinger Publishing. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-4191-4387-8.

- Dutt, Romesh Chunder (2002). The Ramayana and Mahabharata condensed into English verse. Courier Dover Publications. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-486-42506-1.

- Fallon, Oliver (2009). Bhatti's Poem: The Death of Rávana (Bhaṭṭikāvya). New York: New York University Press, Clay Sanskrit Library. ISBN 978-0-8147-2778-2.

- Keshavadas, Sadguru Sant (1988). Ramayana at a Glance. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 211. ISBN 978-81-208-0545-3.

- Goldman, Robert P. (1990). The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India: Balakanda. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01485-2.

- Goldman, Robert P. (1994). The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India: Kiskindhakanda. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-06661-5.

- Goldman, Robert P. (1996). The Ramayana of Valmiki: Sundarakanda. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-06662-2.

- B. B. Lal (2008). Rāma, His Historicity, Mandir, and Setu: Evidence of Literature, Archaeology, and Other Sciences. Aryan Books. ISBN 978-81-7305-345-0.

- Mahulikar, Dr. Gauri. Effect Of Ramayana On Various Cultures And Civilisations, Ramayan Institute

- Rabb, Kate Milner, National Epics, 1896 – see eText in Project Gutenburg

- Murthy, S. S. N. (November 2003). "A note on the Ramayana" (PDF). Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies. New Delhi. 10 (6): 1–18. ISSN 1084-7561. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2012.

- Prabhavananda, Swami (1979). The Spiritual Heritage of India. Vedanta Press. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-87481-035-6. (see also Wikipedia article on book)

- Raghunathan, N. (transl.), Srimad Valmiki Ramayanam, Vighneswara Publishing House, Madras (1981)

- Rohman, Todd (2009). "The Classical Period". In Watling, Gabrielle; Quay, Sara. Cultural History of Reading: World literature. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-33744-4.

- Sattar, Arshia (transl.) (1996). The Rāmāyaṇa by Vālmīki. Viking. p. 696. ISBN 978-0-14-029866-6.

- Sundararajan, K.R. (1989). "The Ideal of Perfect Life : The Ramayana". In Krishna Sivaraman; Bithika Mukerji. Hindu spirituality: Vedas through Vedanta. The Crossroad Publishing Co. pp. 106–126. ISBN 978-0-8245-0755-8.

- A different Song – Article from "The Hindu" 12 August 2005 – "The Hindu : Entertainment Thiruvananthapuram / Music : A different song". Hinduonnet.com. 12 August 2005. Archived from the original on 27 October 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Valmiki's Ramayana illustrated with Indian miniatures from the 16th to the 19th century, 2012, Editions Diane de Selliers, ISBN 9782903656768

Further reading[edit]

- Sanskrit text

- Electronic version of the Sanskrit text, input by Muneo Tokunaga

- Sanskrit text on GRETIL

- Translations

- Jain Ramayana of Hemchandra English translation; seventh book of the Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra; 1931

- Valmiki Ramayana verse translation by Desiraju Hanumanta Rao, K. M. K. Murthy et al.

- Summary of The Ramayana Summary of Maurice Winternitz, A History of Indian Literature, trans. by S. Ketkar.

- Valmiki Ramayana translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith (1870–1874) (Project Gutenberg)

- The Ramayana condensed into English verse by R. C. Dutt (1899) at archive.org

- Prose translation of the complete Ramayana by M. N. Dutt (1891–1894): Balakandam, Ayodhya Kandam, Aranya Kandam, Kishkindha Kandam, Sundara Kandam, Yuddha Kandam, Uttara Kandam

- Rāma the Steadfast: an early form of the Rāmāyaṇa translated by J. L. Brockington and Mary Brockington. Penguin, 2006. ISBN 0-14-044744-X.

- Secondary sources

- Jain, Meenakshi. (2013). Rama and Ayodhya. Aryan Books International, 2013.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ramayan |

| Sanskrit Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- A condensed verse translation by Romesh Chunder Dutt sponsored by the Liberty Fund

- The Ramayana as a Monomyth from UC Berkeley (archived)

.jpg/125px-Ramapanchayan%2C_Raja_Ravi_Varma_(Lithograph).jpg)