Hatha yoga

_from_Jogapradipika_1830.jpg/220px-Kapala_Asana_(headstand)_from_Jogapradipika_1830.jpg)

Hatha yoga is a branch of yoga, one of the six schools of Hinduism. The Sanskrit word haṭha literally means "force" and thus alludes to a system of physical techniques.[1]:770[2]:527

In India, hatha yoga is associated in popular tradition with the 'Yogis' of the Natha Sampradaya through its mythical founder Matsyendranath. Matsyendranath, also known as Minanath or Minapa in Tibet, is celebrated as a saint in both Buddhist and Hindu tantric and hatha yoga schools. However, James Mallinson associates hatha yoga with the Dashanami Sampradaya and the mystical figure of Dattatreya.[3][4] According to the Dattatreya Yoga Śastra, there are two forms of hatha yoga: one practiced by Yajñavalkya consisting of the eight limbs of ashtanga yoga and another practiced by Kapila consisting of eight mudras. Currently, the oldest dated text to describe hatha yoga, the 11th century CE Amṛtasiddhi, comes from a tantric Buddhist milieu.[5] The oldest texts to use the actual verbiage of hatha are also Vajrayana Buddhist.[2]

In the 20th century, a development of hatha yoga, focusing particularly on asanas (the physical postures), became popular throughout the world as a form of physical exercise. This modern yoga is now colloquially termed simply as "yoga."

Contents

Origins[edit]

Earliest textual references[edit]

According to the Indologist James Mallinson, some Hatha Yoga techniques can be traced back at least to the 1st-century CE, in texts such as the Sanskrit epics (Hinduism) and the Pali canon (Buddhism).[6] The Pali canon contains three passages in which the Buddha describes pressing the tongue against the palate for the purposes of controlling hunger or the mind, depending on the passage.[7] However, there is no mention of the tongue being inserted into the nasopharynx as in true khecarī mudrā. The Buddha used a posture where pressure is put on the perineum with the heel, similar to modern postures used to stimulate Kundalini.[8]

According to Birch, the earliest mentions of Haṭha Yoga specifically are also from Buddhist texts, mainly Tantric works from the 8th century onwards, such as Puṇḍarīka’s Vimalaprabhā commentary on the Kālacakratantra.[9] In this text, Haṭha Yoga is defined within the context of tantric sexual ritual:

"when the undying moment does not arise because the breath is unrestrained [even] when the image is seen by means of withdrawal (pratyahara) and the other (auxiliaries of yoga, i.e. dhyana, pranayama, dharana, anusmrti and samadhi), then, having forcefully (hathena) made the breath flow in the central channel through the practice of nada, which is about to be explained, [the yogi] should attain the undying moment by restraining the bindu of the bodhicitta [i.e. semen] in the vajra [i.e. penis] when it is in the lotus of wisdom [i.e. vagina]".[9]

While the actual means of practice are not specified, the forcing of the breath into the central channel and the restraining of bindu are central features of later haṭhayoga practice texts.[10]

Medieval systematization[edit]

In medieval times, teachings on Yoga were systematized in several texts:

- The Amṛtasiddhi, which dates to the 11th century CE, teaches mahābandha, mahāmudrā, and mahāvedha.[1]:771

- The Dattātreyayogaśāstra, probably composed in the 13th century CE, teaches an eightfold yoga identical with Patañjali's 8 limbs that it attributes to Yajnavalkya and others as well as eight mudras that it says were undertaken by the rishi Kapila and other ṛishis.[1]:771 The Dattātreyayogaśāstra teaches mahāmudrā, mahābandha, khecarīmudrā, jālandharabandha, uḍḍiyāṇabandha, mūlabandha, viparītakaraṇī, vajrolī, amarolī, and sahajolī.[1]:771

- The ̣Śārṅgadharapaddhati is an anthology of verses on a wide range of subjects compiled in 1363 CE, which in its description of Hatha Yoga includes ̣the Dattātreyayogaśāstra’s teachings on five mudrās.[1]:772

- The Vivekamārtaṇḍa, which is contemporaneous with the Dattātreyayogaśāstra, teaches nabhomudrā (i.e. khecarīmudrā), mahāmudrā, viparītakaraṇī and the three bandhas.[1]:771

- The Goraksaśatakạ, which is also contemporaneous with the Dattātreyayogaśāstra, teaches śakticālanīmudrā along with the three bandhas.[1]:771

- The Khecarīvidyā teaches only the method of khecarīmudrā.[1]:771

The methods of the Amṛtasiddhi, Dattātreyayogaśāstra and Vivekamārtaṇḍa are used to raise and conserve bindu (semen, and in women rajas - menstrual fluid) which was seen as the physical essence of life that was constantly dripping down from the head and being lost.[1]:770 These techniques sought to either physically reverse this process (by inverted postures like the viparītakaraṇī) or to use the breath to force bindu upwards through the central channel.[1]:770 Other texts like the Vivekamārtaṇḍa, Goraksaśataka, and Khecarīvidyā also teach the raising of kuṇḍalinī.[1]:771 The aims of these practices were siddhis (supranormal powers such as levitation) and mukti (liberation).[1]:771

Other texts older than the Hathapradīpikā to teach Hatha Yoga ̣mudrās are the Shiva Samhita, Yogabīja, Amaraughaprabodha, and Śārṅgadharapaddhati.[1]:771-772

Classical Hatha yoga[edit]

Hatha Yoga Pradīpika[edit]

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika is one of the most influential texts of Hatha yoga.[11] It was compiled by Svātmārāma in the 15th century CE from earlier hatha yoga texts.[1]:772 These earlier texts were of Vedanta or non-dual Shaiva orientation.[12] From both, the Hatha Yoga Pradīpika borrowed the philosophy of non-duality (advaita). According to James Mallinson, this reliance on non-duality helped Hatha Yoga thrive in the medieval period as non-duality became the "dominant soteriological method in scholarly religious discourse in India".[12]

Hatha Yoga Pradipika lists 35 great yoga siddhas starting with Adi Natha (Hindu god Shiva) followed by Matsyendranath and Gorakshanath.[13] It includes information about shatkarma (six acts of self purification), 15 asana (postures: seated, laying down, and non-seated), pranayama (breathing) and kumbhaka (breath retention), mudras (internalized energetic practices), meditation, chakras (centers of energy), kundalini, nadanusandhana (concentration on inner sound), and other topics.[14]

Hatha Yoga Pradipika is the best known and most widely used Hatha yoga text. It consists of 389 shlokas (verses) in four chapters:[15]

- Chapter 1 with 67 verses deals with setting the proper environment for yoga, ethical duties of a yogi, and asanas (postures)

- Chapter 2 with 78 verses deals with the pranayama (breathing exercises, control of vital energy within) and the satkarmani (body cleansing)

- Chapter 3 with 130 verses discusses the mudras and their benefits.

- Chapter 4 with 114 verses deals with meditation and samadhi as a journey of personal spiritual growth.

Post-Hathapradipika texts[edit]

Post-Hathapradipika texts on Hatha yoga include:[1]:773-774[16]

- Amaraughasasana: a Sharada script manuscript of this Hatha yoga text was copied in 1525 CE. It is notable because fragments of this manuscript have also been found near Kuqa in Xinjiang (China). The text discusses khecarimudra, but calls it saranas.[17]

- Hatha Ratnavali: a 17th-century text that states Hatha yoga consists of ten mudras, eight cleansing methods, nine kumbhakas and 84 asanas (compared to 15 asanas of Hathapradīpikạ̄). The text is also notable for dropping the nadanusandhana (inner sound) technique.[17]

- Hathapradipika Siddhantamuktavali: an early 18th-century text that expands on Hathapradīpikạ̄ by adding practical insights and citations to other Indian texts on yoga.[18]

- Gheranda Samhita: a 17th or 18th-century text that presents Hatha yoga as "ghatastha yoga", according to Mallinson.[18][19] It presents 6 cleansing methods, 32 asanas, 25 mudras and 10 pranayamas.[18] It is one of the most encyclopedic texts on Hatha yoga.[20]

- Jogapradipika: an 18th-century Braj-language text that presents Hatha yoga simply as "yoga", composed by Ramanandi Jayatarama. It presents 6 cleansing methods, 84 asanas, 24 mudras and 8 kumbhakas.[18]

Modern era[edit]

Historically, Hatha yoga has been a broad movement across the Indian traditions, openly available to anyone.[21]

Hatha Yoga, like other methods of yoga, can be practiced by all, regardless of sex, caste, class, or creed. Many texts explicitly state that it is practice alone that leads to success. Sectarian affiliation and philosophical inclination are of no importance. The texts of Hatha Yoga, with some exceptions, do not include teachings on metaphysics or sect-specific practices.

— James Mallinson, Hatha Yoga, Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism[22]

According to Mallinson, Hatha yoga represented a trend towards the democratization of yoga insights and religion similar to the Bhakti movement. It eliminated the need for "either ascetic renunciation or priestly intermediaries, ritual paraphernalia and sectarian initiations".[21] This led to its broad historic popularity in India. Later in the 20th-century, states Mallinson, this disconnect of Hatha yoga from religious aspects and the democratic access of Hatha yoga enabled it to spread worldwide.[23]

Between the 17th and 19th-century, however, the various urban Hindu and Muslim elites and ruling classes viewed Yogis with derision.[24] They were persecuted during the rule of Aurangzeb, who ended a long period of religious tolerance that had defined the rule of his predecessors beginning with Akbar, who famously studied with the yogis and other mystics.[25] Hatha yoga remained popular in rural India. Negative impression for the Hatha yogis continued during the British colonial rule era. According to Mark Singleton, this historical negativity and colonial antipathy likely motivated Swami Vivekananda to make an emphatic distinction between "merely physical exercises of Hatha yoga" and the "higher spiritual path of Raja yoga".[26] This common disdain by the officials and intellectuals slowed the study and adoption of Hatha yoga.[27][28][note 1]

A well-known school of Hatha yoga from the 20th-century is the Divine Life Society founded by Swami Sivananda of Rishikesh (1887–1963) and his many disciples including, among others, Swami Vishnu-devananda – founder of International Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centres; Swami Satyananda – of the Bihar School of Yoga; and Swami Satchidananda of Integral Yoga.[30] The Bihar School of Yoga has been one of the largest Hatha yoga teacher training centers in India but is little known in Europe and the Americas.[31]

Modern yoga[edit]

Modern yoga, of the type seen in the West, has been greatly influenced by the school of Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, who taught from 1924 until his death in 1989. He combined asanas from Hatha yoga with gymnastic exercises to develop a flowing style of physical yoga that placed little or no emphasis on Hatha yoga's spiritual goals.[32] Among his students prominent in popularizing yoga in the West were K. Pattabhi Jois famous for popularizing the vigorous Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga style, B. K. S. Iyengar who emphasized alignment and the use of props, Indra Devi and Krishnamacharya's son T. K. V. Desikachar.[30] Krishnamacharya-linked schools have become widely known in the Western world.[31] Examples of other branded forms of yoga, with some controversies, that make use of Hatha yoga include Anusara Yoga, Ashtanga Yoga, Bikram Yoga, Integral Yoga, Iyengar Yoga, Jivanmukti Yoga, Kundalini Yoga, Kripalu Yoga, Kriya Yoga, Viniyoga, Vinyasa Yoga and White Lotus Yoga.[33] After about 1975, yoga techniques have become increasingly popular globally, in both developed and developing countries.[34]

Practice[edit]

Hatha yoga practice has many elements, both behavioral and of practice. The Hatha yoga texts state that a successful yogi has certain characteristics. Section 1.16 of the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, for example, states these characteristics to be utsaha (enthusiasm, fortitude), sahasa (courage), dhairya (patience), jnana tattva (essence for knowledge), nishcaya (resolve, determination) and tyaga (solitude, renunciation).[13]

In the Western culture, Hatha yoga is typically understood as asanas and it can be practiced as such.[35] In the Indian and Tibetan traditions, Hatha yoga is much more. It extends well beyond being a sophisticated physical exercise system and integrates ideas of ethics, diet, cleansing, pranayama (breathing exercises), meditation and a system for spiritual development of the yogi.[36][37]

Proper diet[edit]

The Hatha yoga texts place major emphasis on mitahara, which connotes "measured diet" or "moderate eating". For example, sections 1.58 to 1.63 and 2.14 of the Hatha Yoga Pradipika and sections 5.16 to 5.32 of Gheranda samhita discuss the importance of proper diet to the body.[38][39] They link the food one eats and one's eating habits to balancing the body and to gaining most benefits from the practice of Hatha yoga. Eating, states Gheranda samhita, is a form of a devotional act to the temple of body, as if one is expressing affection for the gods.[38] Similarly, sections 3.20 and 5.25 of the Shiva Samhita text on Hatha Yoga includes mitahara as an essential part of a Hatha yoga holistic practice.[40]

ब्रह्मचारी मिताहारी तयागी योग-परायणः | अब्दादूर्ध्वं भवेद्सिद्धो नात्र कार्या विछारणा ||

A brahmachari, practicing mitahara (moderate diet) and tyaga (renunciation, solitude), devoted to yoga achieves success in his inquiry and effort within half a year.

— Hathayoga Pradipika, 1.57[41]

Verses 1.57 through 1.63 of the critical edition of Hathayoga Pradipika suggests that taste cravings should not drive one’s eating habits, rather the best diet is one that is tasty, nutritious and likable as well as sufficient to meet the needs of one’s body and for one’s inner self.[42] It recommends that one must “eat only when one feels hungry” and “neither overeat nor eat to completely fill the capacity of one’s stomach; rather leave a quarter portion empty and fill three quarters with quality food and fresh water”.[42]

According to another Hatha Yoga classic Gorakshasataka, eating a controlled diet is one of the three important parts of a complete and successful practice. The text does not provide details or recipes. The text states, according to Mallinson, "food should be unctuous and sweet", one must not overeat and stop when still a bit hungry (leave a quarter of the stomach empty), and whatever one eats should aim to please the Shiva.[43]

Proper body cleansing[edit]

Hatha yoga teaches various steps of inner body cleansing with consultations of one's yoga teacher. Its texts vary in specifics and number of cleansing methods, ranging from simple hygiene practices to the peculiar exercises such as reversing seminal fluid flow.[44] The most common list is called shat-karmani, or six cleansing actions: dhauti (cleanse teeth and body), vasti (cleanse bladder), neti (cleanse nasal passages), trataka (cleanse eyes), nauli (abdominal massage) and kapala-bhati (cleanse phlegm).[44] The actual procedure for cleansing varies by the Hatha yoga text, with some suggesting water wash and others describing the use of cleansing aids such as cloth.[45]

Proper breathing[edit]

Prāṇāyāma is made out of two Sanskrit words prāṇa (प्राण, breath, vital energy, life force)[47][48] and āyāma (आयाम, restraining, extending, stretching).[49][48]

Some Hatha yoga texts teach breath exercises but do not refer to it as Pranayama. For example, Gheranda samhita in section 3.55 calls it Ghatavastha (state of being the pot).[50] In others, the term Kumbhaka or Prana-samrodha replaces Pranayama.[51] Regardless of the nomenclature, proper breathing and the use of breathing techniques during a posture is a mainstay of Hatha yoga. Its texts state that proper breathing exercises cleanses and balances the body.[52]

Pranayama is one of the core practices of Hatha yoga, found in its major texts as one of the limbs regardless of whether the total number of limbs taught are four or more.[53][54][55] It is the practice of consciously regulating breath (inhalation and exhalation), a concept shared with all schools of yoga.[56][57]

This is done in several ways, inhaling and then suspending exhalation for a period, exhaling and then suspending inhalation for a period, slowing the inhalation and exhalation, consciously changing the time/length of breath (deep, short breathing), combining these with certain focussed muscle exercises.[58] Pranayama or proper breathing is an integral part of asanas. According to section 1.38 of Hatha yoga pradipika, Siddhasana is the most suitable and easiest posture to learn breathing exercises.[46]

The different Hatha yoga texts discuss pranayama in various ways. For example, Hatha yoga pradipka in section 2.71 explains it as a threefold practice: recaka (exhalation), puraka (inhalation) and kumbhaka (retention).[59] During the exhalation and inhalation, the text states that three things move: air, prana and yogi's thoughts, and all three are intimately connected.[59] It is kumbhaka where stillness and dissolution emerges. The text divides kumbhaka into two kinds: sahita (supported) and kevala (complete). Sahita kumbhaka is further sub-divided into two types: retention with inhalation, retention with exhalation.[60] Each of these breath units are then combined in different permutations, time lengths, posture and targeted muscle exercises in the belief that these aerate and assist blood flow to targeted regions of the body.[58][61]

Proper posture[edit]

Before starting yoga practice, state the Hatha yoga texts, the yogi must establish a suitable place for the yoga practice. This place is away from all distractions, preferably a mathika (hermitage) that is distant from falling rocks, fire and a damp shifting surface.[62]

| Asanas (postures) in Hatha yoga texts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanskrit name | English | Image | Gheranda Samhita verse #[63] |

Hatha Yoga Pradipika verse #[63][64] |

Shiva Samhita verse #[63] |

| Siddhāsana | Accomplished |

|

2.7 | 1.35-43 | 3.97-101 |

| Padmāsana | Lotus |

|

2.8 | 1.44-49 | 3.102-107 |

| Bhadrasana | Fortunate |

|

2.9-10 | 1.53-54 | Absent |

| Muktāsana | Freedom |

|

2.11 | Absent | Absent |

| Vajrāsana | Thunderbolt |

|

2.12 | Absent | Absent |

| Svastikāsana | Auspicious | 2.13 | 1.19 | 3.113-115 | |

| Siṁhāsana | Lion |

|

2.14-15 | 1.50-52 | Absent |

| Gomukhāsana | Cow face |

|

2.16 | 1.20 | Absent |

| Virasana | Hero |

|

2.17 | Absent | 3.21 |

| Dhanurāsana | Bow |

|

2.18 | 1.25 (variance) |

Absent |

| Śavāsana | Corpse |

|

2.19 | 1.34 | Absent |

| Guptāsana | Secret |

|

2.20 | Absent | Absent |

| Matsyāsana | Fish |

|

2.21 | Absent | Absent |

| Matsyendrāsana | Lord of the fishes |

|

2.22-23 | 1.26-27 | Absent |

| Gorakshasana | Cowherd | 2.24-25 | 1.28-29 | 3.108-112 | |

| Paschimottanasana | Seated Forward Bend |

|

2.26 | 1:30-31 | Absent |

| Utkaṭāsana | Superior |

|

2.27 | Absent | Absent |

| Sankatasana | Contracted | 2.28 | Absent | Absent | |

| Mayūrāsana | Peacock | 2.29-30 | 1.30-31 | Absent | |

| Kukkutasana | Rooster |

|

2.31 | 1.23 | Absent |

| Kūrmāsana | Tortoise |

|

2.32 | 1.22 | Absent |

| Uttana Kurmasana | Raised Tortoise |

|

2.33 | 1.24 | Absent |

| Mandukasana | Frog |

|

2.34 | Absent | Absent |

| Uttana Mandukasana | Raised Frog | 2.35 | Absent | Absent | |

| Vrikshasana | Tree |

|

2.36 | Absent | Absent |

| Garuḍāsana | Eagle |

|

2.37 | Absent | Absent |

| Trishasana | Bull | 2.38 | Absent | Absent | |

| Shalabhasana | Locust (Grasshopper) |

|

2.39 | Absent | Absent |

| Makarāsana | Crocodile | .jpg/120px-Makarasana_Asana_(Crocodile_Posture).jpg)

|

2.40 | Absent | Absent |

| Ushtrasana | Camel |

|

2.41 | Absent | Absent |

| Bhujaṅgāsana | Serpent |

|

2.42-43 | Absent | Absent |

| Yogasana | Union | 2.44-45 | Absent | Absent | |

Once a peaceful stable location has been set, the yogi begins the posture exercises called asanas. These Hatha yoga postures come in numerous forms. For a beginner, states the historian of religion Mircea Eliade, these asanas are uncomfortable, typically difficult, cause the body shakes and typically unbearable to hold for extended periods of time.[65] However, with repetition and persistence, as the muscle tone improves, the effort reduces and posture improves. According to the Hatha yoga texts, each posture becomes perfect when the "effort disappears", one no longer thinks about the posture and one's body position, breathes normally per pranayama, and is able to dwell in one's meditation (anantasamapattibhyam).[66]

The asanas discussed in different Hatha yoga texts vary significantly.[67] Unlike ancient yoga texts of Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism, it is the Hatha yoga texts that provide step by step methodology on how to enter into an asana. The Hindu text Gheranda samhita, for example, in section 2.8 describes the padmasana for meditation.[68] Most asanas are inspired by nature, such as a form of union with symmetric, harmonious flowing shapes of animals, birds or plants.[69]

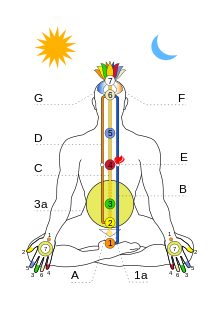

Kundalini in later hatha yoga[edit]

Early hatha yoga was used to prevent the dripping of bindu (semen) from the heads of men.[1]:770 The two early hatha yoga techniques to achieve this were inverted poses such as Viparita Karani, known as the reverser, or to make breath flow into the center channel which forces bindu up.[1]:770

However, in later hatha yoga, the Kaula visualization of Kuṇḍalini rising through a system of chakras is overlaid onto the earlier bindu-oriented system.[1]:770, 774 The aim was to access amṛta (the nectar of immortality) situated in the head, which subsequently floods the body.[1]:770, 774 This goal is in contradiction with the early hatha yoga goal of preserving bindu.[1]:770, 774

Meditation[edit]

The Hatha yoga pradipika text dedicates almost a third of its verses to meditation.[15] Similarly, other major texts of Hatha yoga such as Shiva samhita and Gheranda samhita discuss meditation.[71] In all three texts, meditation is the ultimate goal of all the preparatory cleansing, asanas, pranayama and other steps. The aim of this meditation is to realize Nada-Brahman, or the complete absorption and union with the Brahman through inner mystic sound.[71] According to Guy Beck – a professor of Religious Studies known for his studies on Yoga and music, a Hatha yogi in this stage of practice seeks "inner union of physical opposites", into an inner state of samadhi that is described by Hatha yoga texts in terms of divine sounds, and as a union with Nada-Brahman in musical literature of ancient India.[72]

Goals[edit]

The aims of Hatha yoga in various Indian traditions have been the same as those of other varieties of yoga. These include physical siddhis (special powers, bodily benefits such as slowing age effects, magical powers) and spiritual liberation (moksha, mukti).[73][74] According to Mikel Burley, some of the siddhis are symbolic references to the cherished soteriological goals of Indian religions. For example, the Vayu Siddhi or "conquest of the air" literally implies rising into the air as in levitation, but it likely has a symbolic meaning of "a state of consciousness into a vast ocean of space" or "voidness" ideas found respectively in Hinduism and Buddhism.[75]

Some traditions such as the Kaula tantric sect of Hinduism and Sahajiya tantric sect of Buddhism pursued more esoteric goals such as alchemy (Nagarjuna, Carpita), magic, kalavancana (cheating death) and parakayapravesa (entering another's body).[73][76][77] James Mallinson, however, disagrees and suggests that such fringe practices are far removed from the mainstream Yoga's goal as meditation-driven means to liberation in Indian religions.[78] The majority of historic Hatha yoga texts do not give any importance to siddhis.[79] The mainstream practice considered the pursuit of magical powers as a distraction or hindrance to Hatha yoga's ultimate aim of spiritual liberation, self-knowledge or release from rebirth that the Indian traditions call mukti or moksha.[73][74]

The goals of Hatha yoga, in its earliest texts, were linked to mumukshu (seeker of liberation, moksha). The later texts added and experimented with the goals of bubhukshu (seeker of enjoyment, bhoga).[80]

Differences from Patanjali yoga[edit]

Hatha yoga is a branch of yoga. It shares numerous ideas and doctrines with other forms of yoga, such as the more ancient Yoga system taught by Patanjali. The differences are in the addition of some aspects, and different emphasis on other aspects.[81] For example, pranayama is crucial in all yogas, but it is the mainstay of Hatha yoga.[52][82] Mudras and certain kundalini-related ideas are included in Hatha yoga, but not mentioned in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.[83] Patanjali yoga considers asanas important but dwells less on various asanas than the Hatha yoga texts. In contrast, the Hatha yoga texts consider meditation as important but dwell less on meditation methodology than Patanjali yoga.[84]

The Hatha yoga texts acknowledge and refer to Patanjali yoga, attesting to the latter's antiquity. However, this acknowledgment is essentially only in passing, as they offer no serious commentary or exposition of Patanjali's system. This suggests that Hatha yoga developed as a branch of the more ancient yoga.[85] According to P.V. Kane, Patanjali yoga concentrates more on the yoga of the mind, while Hatha yoga focuses on body and health.[86] Some Hindu texts do not recognize this distinction. For example, the Yogatattva Upanishad teaches a system that includes all aspects of the Yogasutras of Patanjali, and all additional elements of Hatha yoga practice.[87]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Mallinson, James (2011). Hatha Yoga Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism Vol. 3 (pp. 770-781). Leiden: Brill.

- ^ a b Birch, Jason (2011). The Meaning of haṭha in Early Haṭhayoga Journal of the American Oriental Society 131.4.

- ^ James Mallinson (2014). The Yogīs’ Latest Trick. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Third Series), 24, pp 165-180. doi:10.1017/S1356186313000734.

- ^ Yoga and Yogis. March 2012. James Mallinson. pg. 26-27.

- ^ Mallinson, James (2016). [1] The Amṛtasiddhi: Hathayoga's tantric Buddhist source text

- ^ Mallinson, James (2011). Hatha Yoga Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism Vol. 3 (pp. 770-781). Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Mallinson, James 2007. The Khecarīvidyā of Adinathā. London: Routledge. pg.17-19.

- ^ Mallinson, James. "Śāktism and Haṭhayoga." In: Goddess Traditions in Tantric Hinduism: History, Practice and Doctrine, edited by Bjarne Wernicke Olesen London: Routledge, 2016. pp. 109-140. pg.120:"The Buddha himself is said to have tried both pressing his tongue to the back of his mouth, in a manner similar to that of the hathayogic khecarīmudrā, and ukkutikappadhāna, a squatting posture which may be related to hathayogic techniques such as mahāmudrā, mahābandha, mahāvedha, mūlabandha, and vajrāsana in which pressure is put on the perineum with the heel, in order to force upwards the breath or Kundalinī."

- ^ a b Birch, Jason (2011). The Meaning of haṭha in Early Haṭhayoga Journal of the American Oriental Society 131.4.

- ^ Birch, Jason (2011). The Meaning of haṭha in Early Haṭhayoga Journal of the American Oriental Society 131.4.

- ^ Bjarne Wernicke Olesen (2015). Goddess Traditions in Tantric Hinduism: History, Practice and Doctrine. Taylor & Francis. p. 147. ISBN 978-1317585213.

- ^ a b Mallinson, James (2013). "Hathayoga's Philosophy: A Fortuitous Union of Non-Dualities". Journal of Indian Philosophy. Springer Nature. 42 (1): 225–247. doi:10.1007/s10781-013-9217-0.

- ^ a b Svatmarama (Sanskrit); Brian Akers (English Transl) (2002). The Hatha Yoga Pradipika. Yoga Vidya. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-0-9899966-4-8.

- ^ James Mallinson 2011, pp. 772-773.

- ^ a b Mikel Burley 2000, pp. 6-7.

- ^ Mark Singleton 2010, pp. 27-28.

- ^ a b James Mallinson 2011, p. 773.

- ^ a b c d James Mallinson 2011, p. 774.

- ^ Mark Singleton 2010, p. 28.

- ^ James Mallinson (2004). The Gheranda Samhita: The Original Sanskrit and an English Translation. Yoga Vidya. pp. ix–x. ISBN 9780971646636.

- ^ a b James Mallinson 2012, p. 26.

- ^ James Mallinson 2011, p. 778.

- ^ James Mallinson 2011, pp. 778-779.

- ^ David Gordon White 2012, pp. 8-9.

- ^ Shail Mayaram 2003, pp. 40-41.

- ^ Mark Singleton 2010, pp. 69-72, 77-79.

- ^ Mark Singleton 2010, pp. 77-78.

- ^ White 2011, pp. 20-22.

- ^ Mark Singleton 2010, pp. 78-81.

- ^ a b James Mallinson 2011, p. 779.

- ^ a b Mark Singleton 2010, p. 213 note 14.

- ^ Singleton, Mark (2010). Yoga body : the origins of modern posture practice. Oxford University Press. pp. 88, 175–210. ISBN 978-0-19-539534-1. OCLC 318191988.

- ^ Gerald James Larson, Ram Shankar Bhattacharya & Karl H. Potter 2008, pp. 151-159.

- ^ Michelis, Elizabeth De (2007). "A Preliminary Survey of Modern Yoga Studies". Asian Medicine. Brill Academic Publishers. 3 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1163/157342107x207182., Quote: "Modern yoga has emerged as a transnational global phenomenon during the course of the twentieth century and from about 1975 onwards it has progressively become acculturated in many different developed or developing societies and milieus worldwide."

- ^ Richard Rosen 2012, pp. 3-4.

- ^ Mikel Burley 2000, pp. ix-x, 6-12.

- ^ Thubten Yeshe (2005). The Bliss of Inner Fire: Heart Practice of the Six Yogas of Naropa. Wisdom Publications. pp. 97–130. ISBN 978-0861719785.

- ^ a b Richard Rosen 2012, pp. 25-26.

- ^ Mircea Eliade 2009, p. 231 with footnote 78.

- ^ James Mallinson 2007, pp. 44, 110.

- ^ Hathayoga Pradipika Brahmananda, Adyar Library, The Theosophical Society, Madras India (1972)

- ^ a b K. S. Joshi, Speaking of Yoga and Nature-Cure Therapy, Sterling Publishers, ISBN 978-1-84557-045-3, page 65-66

- ^ White 2011, pp. 258-259, 267.

- ^ a b Gerald James Larson, Ram Shankar Bhattacharya & Karl H. Potter 2008, p. 141.

- ^ Mark Singleton 2010, pp. 28-30.

- ^ a b Mikel Burley 2000, pp. 199-200.

- ^ prAna Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany

- ^ a b Richard Rosen 2012, p. 220.

- ^ Monier-Williams, Āyāma, Sanskrit-English Dictionary with Etymology, Oxford University Press

- ^ Mark Singleton 2010, p. 213 note 12.

- ^ Mark Singleton 2010, pp. 9, 29.

- ^ a b Mark Singleton 2010, pp. 29, 146-153.

- ^ Alain Daniélou 1955, pp. 57-62.

- ^ Mikel Burley 2000, pp. 8-10, 59, 99.

- ^ Richard Rosen 2012, pp. 220-223.

- ^ Mikel Burley 2000, pp. 8-10, 59-63.

- ^ Hariharānanda Āraṇya (1983), Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0873957281, pages 230-236

- ^ a b Mikel Burley 2000, pp. 202-219.

- ^ a b Mikel Burley 2000, pp. 202-203.

- ^ Mikel Burley 2000, pp. 202-205.

- ^ Mircea Eliade 2009, pp. 55-60.

- ^ Mikel Burley 2000, pp. 34-35.

- ^ a b c Richard Rosen 2012, pp. 80-81.

- ^ Gerald James Larson, Ram Shankar Bhattacharya & Karl H. Potter 2008, pp. 491-492.

- ^ Mircea Eliade 2009, p. 53.

- ^ Mircea Eliade 2009, pp. 53-54, 66-70.

- ^ Richard Rosen 2012, pp. 78-88.

- ^ Mircea Eliade 2009, pp. 53-54.

- ^ Mircea Eliade 2009, pp. 54-55.

- ^ James Mallinson 2008, pp. 231-237 notes 400, 433-434.

- ^ a b Guy L. Beck 1995, pp. 102-103.

- ^ Guy L. Beck 1995, pp. 107-110.

- ^ a b c James Mallinson 2011, p. 770.

- ^ a b Mikel Burley 2000, pp. 44-50, 99-100, 219-220.

- ^ Mikel Burley 2000, pp. 203-204.

- ^ Paul E. Muller-Ortega (31 March 2010). Triadic Heart of Siva, The: Kaula Tantricism of Abhinavagupta in the Non-dual Shaivism of Kashmir. State University of New York Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-1-4384-1385-3.

- ^ White 2011, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Mallinson, James (2013). "The Yogīs' Latest Trick". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Cambridge University Press (CUP). 24 (1): 165–180. doi:10.1017/s1356186313000734.

- ^ James Mallinson 2011b, pp. 329-330.

- ^ James Mallinson 2011b, p. 328.

- ^ Mikel Burley 2000, p. 10.

- ^ Mikel Burley 2000, pp. 10, 59-61, 99.

- ^ Mikel Burley 2000, pp. 6-12, 60-61.

- ^ Mikel Burley 2000, pp. 10, 59-63.

- ^ Gerald James Larson, Ram Shankar Bhattacharya & Karl H. Potter 2008, pp. 139-147.

- ^ Gerald James Larson, Ram Shankar Bhattacharya & Karl H. Potter 2008, p. 140.

- ^ Gerald James Larson, Ram Shankar Bhattacharya & Karl H. Potter 2008, pp. 140-141.

Bibliography[edit]

- Mikel Burley (2000). Haṭha-Yoga: Its Context, Theory, and Practice. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1706-7.

- Bajpai, R.S. The Splendours And Dimensions Of Yoga 2 Vols. Set, New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers & Distri (2002), ISBN 9788171569649

- Guy L. Beck (1995). Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1261-1.

- Alain Daniélou (1955). Yoga: the method of re-integration. University Books. ISBN 978-0766133143.

- Mircea Eliade (2009). Yoga: Immortality and Freedom. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-14203-3.

- Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (2007). "Hatha Yoga". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-04-03.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

- Fernando Tola, Carmen Dragonetti, K. Dad Prithipaul, The Yogasūtras of Patañjali on concentration of mind. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass (1987).

- Gerald James Larson; Ram Shankar Bhattacharya; Karl H. Potter (2008). Yoga: India's Philosophy of Meditation. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-3349-4.

- James Mallinson (2007). The Shiva Samhita: A Critical Edition. Yoga Vidya. ISBN 978-0-9716466-5-0.

- James Mallinson (2008). The Khecarividya of Adinatha: A Critical Edition and Annotated Translation of an Early Text of Hathayoga. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-16642-8.

- James Mallinson (2011). Knut A. Jacobsen; et al., eds. Haṭha Yoga in the Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 3. Brill Academic. pp. 770–781. ISBN 978-90-04-27128-9.

- James Mallinson (2011b). Knut Jacobsen, ed. Siddhi and Mahāsiddhi in Early Haṭhayoga in Yoga Powers: Extraordinary Capacities Attained Through Meditation and Concentration. Brill Academic. pp. 327–344.

- James Mallinson (2012). M Moses and E Stern, ed. "Yoga and Yogis". Namarupa. 3 (15): 1–27.

- James Mallinson (2014). "Haṭhayoga's Philosophy: A Fortuitous Union of Non-Dualities". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 42 (1): 225–247. doi:10.1007/s10781-013-9217-0.

- Shail Mayaram (2003). Against History, Against State: Counterperspectives from the Margins. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12730-1.

- Maehle, Gregor. Ashtanga Yoga The Intermediate Series: Mythology, Anatomy, and Practice, Novato, CA: New World Library (2012), ISBN 9781577319870.

- Richard Rosen (2012). Original Yoga: Rediscovering Traditional Practices of Hatha Yoga. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-0-8348-2740-0.

- Mark Singleton (2010). Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974598-2.

- Swami Sivananda Radha, Hatha Yoga: The Hidden Language, Secrets and Metaphors, Timeless Books (1 May 2006), ISBN 1-932018-13-1.

- White, Ganga. Yoga Beyond Belief: Insights to Awaken and Deepen Your Practice, Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books (2007), ISBN 9781556436468.

- David Gordon White (2012). The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-14934-9.

- White, David Gordon (2011). Yoga in Practice. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1-4008-3993-9.

External links[edit]

- Yoga-Technique in the Great Epic, E. Washburn Hopkins, Journal of the American Oriental Society (1901)

- On the Meaning of Yoga, KS Joshi, Philosophy East and West (1965)

- Indian Spirituality in the West: A Bibliographical Mapping, Robert A. McDermott, Philosophy East and West (1975)

- Yoga as spiritual but not religious: A pragmatic perspective, Peter H. Van Ness, American Journal of Theology & Philosophy (1999)

_LACMA_M.2011.156.4_(1_of_2).jpg/170px-Female_Ascetics_(Yoginis)_LACMA_M.2011.156.4_(1_of_2).jpg)