Toric code

The toric code is a topological quantum error correcting code, and an example of a stabilizer code, defined on a two-dimensional spin lattice [1] It is the simplest and most well studied of the quantum double models.[2] It is also the simplest example of topological order—Z2 topological order (first studied in the context of Z2 spin liquid in 1991).[3][4] The toric code can also be considered to be a Z2 lattice gauge theory in a particular limit.[5] It was introduced by Alexei Kitaev.

The toric code gets its name from its periodic boundary conditions, giving it the shape of a torus. These conditions give the model translational invariance, which is useful for analytic study. However, experimental realization requires open boundary conditions, allowing the system to be embedded on a 2D surface. The resulting code is typically known as the planar code. This has identical behaviour to the toric code in most, but not all, cases.

Contents

Error correction and computation[edit]

The toric code is defined on a two-dimensional lattice, usually chosen to be the square lattice, with a spin-½ degree of freedom located on each edge. They are chosen to be periodic. Stabilizer operators are defined on the spins around each vertex and plaquette[definition needed] (or face)[clarification needed] of the lattice as follows,

Where here we use to denote the edges touching the vertex , and to denote the edges surrounding the plaquette . The stabilizer space of the code is that for which all stabilizers act trivially, hence,

for any state . For the toric code, this space is four-dimensional, and so can be used to store two qubits of quantum information. This can be proven by considering the number of independent stabilizer operators. The occurrence of errors will move the state out of the stabilizer space, resulting in vertices and plaquettes for which the above condition does not hold. The positions of these violations is the syndrome of the code, which can be used for error correction.

The unique nature of the topological codes, such as the toric code, is that stabilizer violations can be interpreted as quasiparticles. Specifically, if the code is in a state such that,

,

a quasiparticle known as an anyon can be said to exist on the vertex . Similarly violations of the are associated with so called anyons on the plaquettes. The stabilizer space therefore corresponds to the anyonic vacuum. Single spin errors cause pairs of anyons to be created and transported around the lattice.

When errors create an anyon pair and move the anyons, one can imagine a path connecting the two composed of all links acted upon. If the anyons then meet and are annihilated, this path describes a loop. If the loop is topologically trivial, it has no effect on the stored information. The annihilation of the anyons, in this case, corrects all of the errors involved in their creation and transport. However, if the loop is topologically non-trivial, though re-annihilation of the anyons returns the state to the stabilizer space it also implements a logical operation on the stored information. The errors, in this case, are therefore not corrected but consolidated.

Let us consider the noise model for which bit and phase errors occur independently on each spin, both with probability p. When p is low, this will create sparsely distributed pairs of anyons which have not moved far from their point of creation. Correction can be achieved by identifying the pairs that the anyons were created in (up to an equivalence class), and then re-annihilating them to remove the errors. As p increases, however, it becomes more ambiguous as to how the anyons may be paired without risking the formation of topologically non-trivial loops. This gives a threshold probability, under which the error correction will almost certainly succeed. Through a mapping to the random-bond Ising model, this critical probability has been found to be around 11%.[6]

Other error models may also be considered, and thresholds found. In all cases studied so far, the code has been found to saturate the Hashing bound. For some error models, such as biased errors where bit errors occur more often than phase errors or vice versa, lattices other than the square lattice must be used to achieve the optimal thresholds.[7][8]

These thresholds are upper limits and are useless unless efficient algorithms are found to achieve them. The most well-used algorithm is minimum weight perfect matching.[9] When applied to the noise model with independent bit and flip errors, a threshold of around 10.5% is achieved. This falls only a little short of the 11% maximum. However, matching does not work so well when there are correlations between the bit and phase errors, such as with depolarizing noise.

The means to perform quantum computation on logical information stored within the toric code has been considered, with the properties of the code providing fault-tolerance. It has been shown that extending the stabilizer space using 'holes', vertices or plaquettes on which stabilizers are not enforced, allows many qubits to be encoded into the code. However, a universal set of unitary gates cannot be fault-tolerantly implemented by unitary operations and so additional techniques are required to achieve quantum computing. For example, universal quantum computing can be achieved by preparing magic states via encoded quantum stubs called tidBits used to teleport in the required additional gates when replaced as a qubit. Furthermore, preparation of magic states must be fault tolerant, which can be achieved by magic state distillation on noisy magic states. A measurement based scheme for quantum computation based upon this principle has been found, whose error threshold is the highest known for a two-dimensional architecture.[10]

Hamiltonian and self-correction[edit]

Since the stabilizer operators of the toric code are quasilocal, acting only on spins located near each other on a two-dimensional lattice, it is not unrealistic to define the following Hamiltonian,

The ground state space of this Hamiltonian is the stabilizer space of the code. Excited states correspond to those of anyons, with the energy proportional to their number. Local errors are therefore energetically suppressed by the gap, which has been shown to be stable against local perturbations.[11] However, the dynamic effects of such perturbations can still cause problems for the code.[12][13]

The gap also gives the code a certain resilience against thermal errors, allowing it to be correctable almost surely for a certain critical time. This time increases with , but since arbitrary increases of this coupling are unrealistic, the protection given by the Hamiltonian still has its limits.

The means to make the toric code, or the planar code, into a fully self-correcting quantum memory is often considered. Self-correction means that the Hamiltonian will naturally suppress errors indefinitely, leading to a lifetime that diverges in the thermodynamic limit. It has been found that this is possible in the toric code only if long range interactions are present between anyons.[14][15] Proposals have been made for realization of these in the lab [16] Another approach is the generalization of the model to higher dimensions, with self-correction possible in 4D with only quasi-local interactions.[17]

Anyon model[edit]

As mentioned above, so called and quasiparticles are associated with the vertices and plaquettes of the model, respectively. These quasiparticles can be described as anyons, due to the non-trivial effect of their braiding. Specifically, though both species of anyons are bosonic with respect to themselves, the braiding of two 's or 's having no effect, a full monodromy of an and an will yield a phase of . Such a result is not consistent with either bosonic or fermionic statistics, and hence is anyonic.

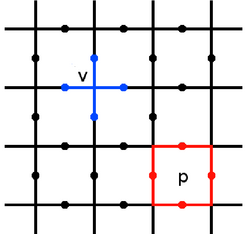

The anyonic mutual statistics of the quasiparticles demonstrate the logical operations performed by topologically non-trivial loops. Consider the creation of a pair of anyons followed by the transport of one around a topologically nontrivial loop, such as that shown on the torus in blue on the figure above, before the pair are reannhilated. The state is returned to the stabilizer space, but the loop implements a logical operation on one of the stored qubits. If anyons are similarly moved through the red loop above a logical operation will also result. The phase of resulting when braiding the anyons shows that these operations do not commute, but rather anticommute. They may therefore be interpreted as logical and Pauli operators on one of the stored qubits. The corresponding logical Pauli's on the other qubit correspond to an anyon following the blue loop and an anyon following the red. No braiding occurs when and pass through parallel paths, the phase of therefore does not arise and the corresponding logical operations commute. This is as should be expected since these form operations acting on different qubits.

Due to the fact that both and anyons can be created in pairs, it is clear to see that both these quasiparticles are their own antiparticles. A composite particle composed of two anyons is therefore equivalent to the vacuum, since the vacuum can yield such a pair and such a pair will annihilate to the vacuum. Accordingly, these composites have bosonic statistics, since their braiding is always completely trivial. A composite of two anyons is similarly equivalent to the vacuum. The creation of such composites is known as the fusion of anyons, and the results can be written in terms of fusion rules. In this case, these take the form,

Where denotes the vacuum. A composite of an and an is not trivial. This therefore constitutes another quasiparticle in the model, sometimes denoted , with fusion rule,

From the braiding statistics of the anyons we see that, since any single exchange of two 's will involve a full monodromy of a constituent and , a phase of will result. This implies fermionic self-statistics for the 's.

Generalizations[edit]

The use of a torus is not required to form an error correcting code. Other surfaces may also be used, with their topological properties determining the degeneracy of the stabilizer space. In general, quantum error correcting codes defined on two-dimensional spin lattices according to the principles above are known as surface codes.[18]

It is also possible to define similar codes using higher-dimensional spins. These are the quantum double models[19] and string-net models,[20] which allow a greater richness in the behaviour of anyons, and so may be used for more advanced quantum computation and error correction proposals.[21] These not only include models with Abelian anyons, but also those with non-Abelian statistics.[22]

Experimental progress[edit]

The most explicit demonstration of the properties of the toric code has been in state based approaches. Rather than attempting to realize the Hamiltonian, these simply prepare the code in the stabilizer space. Using this technique, experiments have been able to demonstrate the creation, transport and statistics of the anyons.[23] More recent experiments have also been able to demonstrate the error correction properties of the code.[24]

For realizations of the toric code and its generalizations with a Hamiltonian, much progress has been made using Josephson junctions. The theory of how the Hamiltonians may be implemented has been developed for a wide class of topological codes.[25] An experiment has also been performed, realizing the toric code Hamiltonian for a small lattice, and demonstrating the quantum memory provided by its degenerate ground state.[26]

Other theoretical work towards experimental realizations is based on cold atoms. A toolkit of methods that may be used to realize topological codes with optical lattices has been explored, [27] as have experiments concerning minimal instances of topological order.[28] Progress is also being made into simulations of the toric model with Rydberg atoms, in which the Hamiltonian and the effects of dissipative noise can be demonstrated.[29]

References[edit]

- ^ A. Y. Kitaev, Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Quantum Communication and Measurement, Ed. O. Hirota, A. S. Holevo, and C. M. Caves (New York, Plenum, 1997).

- ^ A. Kitaev, Ann. Phys. 321, 2 (2006).

- ^ N. Read and Subir Sachdev, Large-N expansion for frustrated quantum antiferromagnets, Phys. Rev. Lett. 66 1773 (1991)

- ^ Xiao-Gang Wen, Mean Field Theory of Spin Liquid States with Finite Energy Gaps and Topological Orders, Phys. Rev. B44, 2664 (1991).

- ^ E. Fradkin and S. Shenker, Phys. Rev. D 19, 3682–3697 (1979)

- ^ E. Dennis, A. Kitaev, A. Landahl, J. Preskill, J. Math. Phys. 43, 4452 (2002).

- ^ B. Roethlisberger, et al. Phys. Rev. A 85, 022313 (2012).

- ^ H. Bombin, et al. Phys. Rev. X 2, 021004 (2012).

- ^ Edmonds, Jack (1965). "Paths, trees, and flowers". Can. J. Math. 17: 449–467.

- ^ R. Raussendorf, J. Harrington, Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 190504 (2007); R. Raussendorf, J. Harrington and K. Goyal, New J. Phys. 9, 199, (2007).

- ^ S. Bravyi, M. Hastings and S. Michalakis, J. Math. Phys. 51, 093512 (2010)

- ^ F. Pastawski, A. Kay, N. Schuch, I. Cirac, arXiv:0911.3843 (2009)

- ^ C. D. Freeman, C. M. Herdman, D. M. Gorman, K. B. Whaley, Phys. Rev. B 90, 134302 (2014)

- ^ A. Hamma, C. Castelnovo, C. Chamon, Phys. Rev. B 79, 245122 (2009).

- ^ S. Chesi, B. Rothlisberger, D. Loss, Phys. Rev. A 82, 022305 (2010).

- ^ F. Pedrocchi, et al., Phys. Rev. B 83, 115415 (2011).

- ^ R. Alicki, et al., Open Syst. Inf. Dyn. 17, 1 (2010).

- ^ J. Ghosh, A. G. Fowler and M. R. Geller, Phys. Rev. A 86, 062318 (2012).

- ^ S. S. Bullock and G. K. Brennen, J. Phys. A 40, 3481-3505 (2007).

- ^ Levin, Michael A. and Xiao-Gang Wen (12 January 2005). "String-net condensation: A physical mechanism for topological phases". Physical Review B. 71 (45110): 21. arXiv:cond-mat/0404617. Bibcode:2005PhRvB..71d5110L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.71.045110.

- ^ J. R. Wootton, V. Lahtinen, B. Doucot and J. K. Pachos, arXiv:0908.0708 (2009).

- ^ M. Aguado, G. K. Brennen, F. Verstraete and J. I. Cirac, Rev. Lett. 101, 260501 (2008); G. K. Brennen, M. Aguado, and J. I. Cirac, New J. Phys. 11, 053009 (2009).

- ^ J. K. Pachos, W. Wieczorek, et al., New J. Phys. 11, 083010 (2009); C.-Y. Lu, et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 030502 (2009).

- ^ Xing-Can Yao et al., Nature 482, 489-494 (2012).

- ^ B. Doucot, L. B. Ioffe and J. Vidal, Phys. Rev. B 69, 214501 (2004).

- ^ S. Gladchenko, D. Olaya, E. Dupont-Ferrier, B. Doucot, L. B. Ioffe, M. E. Gershenson, Nat. Phys. 5, 48 - 53 (2009).

- ^ A. Micheli, G. K. Brennen and P. Zoller, Nat. Phys. 2, 341 - 347 (2006).

- ^ B. Paredes and I. Bloch, Phys. Rev. A, 77, 023603 (2008).

- ^ H, Weimer, M. Müller, I. Lesanovsky, P. Zoller and H. P. Büchler, Nat. Phys. 6, 382 - 388 (2010).