California English

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| California English | |

|---|---|

| Region | California |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

California English (or Californian English) collectively refers to American English in California, particularly an emerging youthful variety, mostly associated with speakers of urban and coastal California.[1][2] California is home to a highly diverse population, which is reflected in the historical and continuing formation of California English, whose emergent vowel shift was only first noted by linguists in the 1980s,[3] best researched in Southern California and the San Francisco Bay Area of Northern California.[3] Since that time, unique California speech has been mostly associated in American popular culture with adolescent and young-adult speakers of coastal California; the possibility that it is, in fact, an age-specific variety of English is one hypothesis that has been proposed but not confirmed.[4] Other documented California English includes a "country" accent associated with rural and inland white Californians as well as unique California varieties of Chicano English associated with Mexican Americans.

Contents

History[edit]

English was first spoken on a wide scale in the area now known as California following the influx of English-speakers from the United States, Canada, and Europe during the California Gold Rush. The English-speaking population grew rapidly with further settlement, which included large populations from the Northeast, South, and the Midwest. The dialects brought by these pioneers were the basis for the development of the modern language: a mixture of settlers from the Midwest and the Border South produced the rural dialect of Northern California, whereas settlers from the Lower Midwest and the South, (especially Missouri and Texas), produced the rural dialect of Southern California.[citation needed]

Before World War I, the variety of speech types reflected the differing origins of these early inhabitants. A distinctly Southwestern drawl could be heard in Southern California.[citation needed] When a collapse in commodity prices followed World War I, many bankrupted Midwestern farmers migrated to California from Nebraska, Ohio, Illinois, Minnesota, and Iowa contributing to a new homogenized speech in urban sprawl, where teachers banned "ain't", 'awl' (oil),[5] and "ahll" (I'll). Subsequently, incoming groups with differing speech, such as the speakers of Highland Southern during the 1930s, have been absorbed within a generation. The Great Depression's Dust Bowl migration re-introduced a purer Southwestern accent to the West Coast in the 1920s and 30s. A California accent with notable Southern features is still spoken by some Californians of the Central Valley, especially around Kern County (centered on Bakersfield), an area historically associated with California "Okies."[6]

California's status as a relatively young state is significant in that it has not had centuries for regional patterns to emerge and grow (compared to, say, some East Coast or Southern dialects). Linguists who studied English as spoken in California before and in the period immediately after World War II tended to find few, if any, distinct patterns unique to the region.[7]

However, several decades later, with a more settled population and continued immigration from all over the globe, a noteworthy set of emerging characteristics of California English had begun to attract notice by linguists from the late 20th century onward. As more people moved into the state, all those groups, ranging from a diverse variety of backgrounds, began to pick up different elements of spoken language from one another.[8]

Phonological overview[edit]

California English mostly aligns to typical American speech. Like most American (and all Western American) accents, California English is rhotic (pronouncing all R's, unlike in most of England, where R's are often "dropped" after vowel sounds).

The following vowel diagram represents the relative positions of the stressed pure vowels of the accent, based on nine speakers from southern California.[9] Notable is the absence of /ɔ/ (the vowel sound of caught, stalk, clawed, etc.), which has completely merged with /ɑ/ (the vowel sound of cot, stock, clod, etc.), as well as the relatively open quality of /ɪ/ due to the California vowel shift discussed below.

Several phonological processes have been identified as being particular to California English. However, these vowel changes are by no means universal in Californian speech, and any single Californian's speech may only have some or none of the changes identified below. These sounds might also be found in the speech of some people from areas outside of California.[citation needed]

- Front vowels are raised before /ŋ/, so that the traditional "short a" /æ/ and "short i" /ɪ/ sounds are raised to the "long a" [e] and "long ee" [i] sounds, respectively, when before the ng sound /ŋ/.[citation needed] This change makes for minimal pairs such as king and keen, both having the same vowel [i], though this pronunciation is not spread evenly and the more common American pronunciation [kʰɪŋ] still exists in many areas of California. In other contexts, /ɪ/ (as in bit, rich, quick, etc.) has a fairly open pronunciation, as indicated in the vowel chart here. Similarly, a word like rang will often have the same vowel as rain in California English, rather than the same vowel as ran.

- Before /n/ or /m/ (as in ran or ram), /æ/ is raised and diphthongized to [eə] or [ɪə] (a widespread shift throughout most American English). Elsewhere, /æ/ is slightly lowered in the direction of [a] (something like the open a sound in Spanish or Italian), as a result of the California vowel shift (see below).

- Most California speakers do not distinguish between /ɔ/ and /ɑ/ (the vowel sounds in caught versus cot), characteristic of the cot–caught merger.[citation needed]

- The pin–pen merger has been reported occasionally in parts of Inland California from Bakersfield[10] to Trinity County.[11]

California vowel shift[edit]

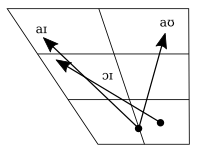

One topic that has begun to receive much attention from scholars in recent decades has been the emergence of a vowel-based chain shift in California. This image on the right illustrates the California vowel shift. The vowel space of the image is a cross-section (as if looking at the interior of a mouth from a side profile perspective); it is a rough approximation of the space in a human mouth where the tongue is located in articulating certain vowel sounds (the left is the front of the mouth closer to the teeth, the right side of the chart being the back of the mouth). As with other vowel shifts, several vowels may be seen moving in a chain shift around the mouth. As one vowel encroaches upon the space of another, the adjacent vowel in turn experiences a movement in order to maximize phonemic differentiation.

For convenience, California English will be compared with a "typical" General American English, abbreviated "GA". /ɛ/ is pulled towards [æ] (wreck and kettle are sounding more like rack and cattle), [æ] is pulled towards [ɑ], and /ɑ/ towards [ɒ] (cot and stock are sounding more like caught and stalk).

Other vowel changes, not part of the chain shift, are /u/ moving beyond [ʉ] (rude and true are almost approaching reed and tree, but with rounded lips), and /oʊ/ moving beyond [ə] (cone and stoke are almost approaching cane and steak, but with rounded lips). /ʊ/ is moving towards [ʌ] (so that, for example, book and could in the California dialect start to sound, to a GA speaker, more like buck and cud), /ʌ/ is moving beyond [ɜ] (mud, glove, what, etc. are sounding like how U.S. southerners pronounce them).[13]

New vowel characteristics of the California Shift are increasingly found among younger speakers. As with many vowel shifts, these significant changes occurring in the spoken language are rarely noticed by average speakers.[citation needed] For example, while some characteristics such as the close central rounded vowel [ʉ] or close back unrounded vowel [ɯ] for /u/ are widespread in Californian speech, the same high degree of fronting for /oʊ/ is common only within certain social groups.[citation needed]

Lexical overview[edit]

The popular image of a typical California speaker often conjures up images of the so-called Valley girls popularized by the 1982 hit song by Frank and Moon Zappa, or "surfer-dude" speech made famous by movies such as Fast Times at Ridgemont High. While many phrases found in these extreme versions of California English from the 1980s may now be considered passé, certain words such as awesome, totally, fer sure, harsh, gnarly, and dude have remained popular in California and have spread to a national, even international, level. The use of the word like for numerous grammatical functions or as conversational "filler" (e.g. in place of thinking sounds "uh" and "um") has also remained popular in California English and is now found in many other varieties of English.[citation needed]

A common example of a more or less exclusively Northern Californian[14] colloquialism is hella (from "(a) hell of a (lot of)", and the euphemistic alternative hecka) to mean "many", "much", "so" or "very".[15] It can be used with both count and mass nouns. For example: "I haven't seen you in hella long"; "There were hella people there"; or "This guacamole is hella good". The word can be casually used multiple times in multiple ways within a single sentence. Pop culture references to "hella" are common, as in the song "Hella Good" by the band No Doubt, which hails from Southern California, and "Hella" by the band Skull Stomp, who come from Northern California.[16]

California, like other Southwestern states, has borrowed many words from Spanish, especially for place names, food, and other cultural items, reflecting the heritage of the Californios. High concentrations of various ethnic groups throughout the state have contributed to general familiarity with words describing (especially cultural) phenomena. For example, a high concentration of Asian Americans from various cultural backgrounds, especially in urban and suburban metropolitan areas in California, has led to the adoption of words like hapa (itself originally a Hawaiian borrowing of English "half"[17]). A person who was hapa was either part European/Islander or part Asian/Islander. Today it refers to a person of mixed racial heritage—especially, but not limited to, half-Asian/half-European-Americans in common California usage and FOB ("fresh off the boat", often a newly arrived Asian immigrant). Not surprisingly, the popularity of cultural food items such as Vietnamese phở and Taiwanese boba in many areas has led to the general adoption of such words among many speakers.[citation needed]

In 1958, essayist Clifton Fadiman pointed out that Northern California is the only place besides England where the word chesterfield is used as a synonym for sofa or couch. Chesterfield is also used in Ontario and the Canadian Prairies.[18]

Freeways[edit]

Californians sometimes refer to the lanes of a multi-lane divided highway by number, "the number 1 lane" (also referred to as "the fast lane") is the lane farthest to the left (not counting the carpool lane), with the lane numbers going up sequentially to the right until the far right lane,[19] which is usually referred to as "the slow lane". In areas where three and occasionally two lane freeways are more common, the lanes are simply the "fast lane", "middle lane" and "slow lane".[citation needed]

In the Los Angeles Metropolitan area, Inland Empire, Coachella Valley and San Diego, freeways are often referred to either by name or by route number (perhaps with a direction suffix), but with the addition of the definite article "the", such as "the 405 North", "the 99" or "the 605 (Freeway)". This usage has been parodied in the recurring Saturday Night Live sketch "The Californians".[20] In contrast, typical Northern California usage omits the definite article.[21][22][23] When Southern California freeways were built in the 1940s and early 1950s, local common usage was primarily the freeway name preceded by the definite article, such as "the Hollywood Freeway".[24] It took several decades for Southern California locals to start to commonly refer to the freeways with the numerical designations, but usage of the definite article persisted. For example, it evolved to "the 605 Freeway" and then shortened to "the 605".[24] That did not occur in Northern California, where usage of the route numbers was more common.[citation needed]

Rural California English[edit]

Aside from the well-studied young urban accent, other California varieties have also been documented, including a so-called "country", "hillbilly", or "twang" variety associated with rural and inland California.[25][26] This California English variety is reminiscent and presumably related to a Southern or South Midland U.S. accent and is recognized among white, outdoors-oriented speakers of the Central Valley; it has even been studied as far north as Trinity County and as far south as Kern County (metropolitan Bakersfield). Similar to the nonstandard accents of the South Midland and Southern United States, speakers of such towns as Redding and Merced have been found to use the word anymore in a positive sense and the word was in place of the standard English plural verb were.[27] Related other features of note include the pin–pen merger, fill–feel merger, and full–fool merger.[25]

The Great Depression's westward Dust Bowl migrations of settlers into California from Southern States, particularly western Oklahoma, is the presumable cause of this rural white accent's presence in California.[28] Rural Northern California was also settled by Oklahomans and Arkansans, though perhaps more recently in the 1970s and 1980s, due to the region's timber industry boom.[29] However, even in a single town, an individual's identification with working and playing outdoors versus indoors appears to be a determiner of accent more than the authenticity or not of this individual's Southern heritage; for example, this correlates with less educated rural men of Northern California documented as raising the /ɛ/ vowel in a style similar to the Southern drawl.[30]

Other varieties[edit]

Certain varieties of Chicano English are also native to California, sometimes even being spoken by non-Latino Californians.[31][32] One example is East Los Angeles Chicano English, which has been influenced by both Californian and African American Vernacular English.[33]A variety of English attributed to San Francisco (or, more specifically, to older, Irish-American residents of that city's Mission District has faded as the city's ethnic makeup and percentage of residents raised elsewhere has changed.[34]

See also[edit]

- North American English regional phonology

- Boontling

- Chain shift

- Chicano English

- African American Vernacular English

- Hyphy

- Sociolect

- Sociolinguistics

- Spanglish

- Valspeak

- Vowel shift

References[edit]

- ^ Podesva, Robert J., Annette D'Onofrio, Janneke Van Hofwegen, and Seung Kyung Kim (2015). "Country ideology and the California Vowel Shift." Language Variation and Change 48: 28-45. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "California English." Do You Speak American? PBS. Macneil/Lehrer Productions. 2005.

- ^ a b Gordon, Matthew J. (2004). "The West and Midwest: phonology." Kortmann, Bernd, Kate Burridge, Rajend Mesthrie, Edgar W. Schneider and Clive Upton (eds). A Handbook of Varieties of English. Volume 1: Phonology, Volume 2: Morphology and Syntax. Berlin / New York: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 347.

- ^ Ward (2003:41): "fronted features in the young speakers seems to indicate a nascent chain shift in progress, [but] the lack of a true generational age range in the study precludes too strong of a conclusion. Alternatively Hinton et al. also suggest that possibility that the age-specific pattern could also be a function of age-grading, where the faddish speech style of California adolescents is adopted for its prestige value, only to be abandoned as adolescence wanes."

- ^ Upton Sinclair, Oil! (1927).

- ^ Bailey, Brianna (2015). "[newsok.com/article/5420122 Read this, y'all: Is the Okie dialect disappearing?]" NewsOK.

- ^ Walt Wolfram and Ben Ward, editors (2006). American Voices: How Dialects Differ from Coast to Coast. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 140, 234–236. ISBN 978-1-4051-2108-8.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ "Do you speak American? - California English". PBS. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ^ Ladefoged, Peter (1999). "American English". In Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, 41–44, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63751-1.

- ^ Warren, Ron; Fulop, Sean A. (2014), "The merged vowel of PIN and PEN as realized in Bakersfield, California", Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 135 (4): 2292, doi:10.1121/1.4877528

- ^ Geenberg, Katherine (2014), What it means to be Norcal Country: Variation and marginalization in rural California, Stanford University

- ^ Eckert, Penelope (date unknown). Diagram. Retrieved from http://www.stanford.edu/~eckert/vowels.html.

- ^ "Professor Penelope Eckert's webpage". Stanford.edu. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- ^ "However, science isn't all that sets Northern California apart from the rest of the world," Sendek wrote. "The area is also notorious for the creation and widespread usage of the English slang 'hella', which typically means 'very', or can refer to a large quantity (e.g. 'there are hella stars out tonight')." [1]

- ^ "Jorge Hankamer WebFest". Ling.ucsc.edu. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- ^ "Lyrics | Skull Stomp - Hella". SongMeanings. 2008-11-02. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- ^ Mary Kawena Pukui, Samuel H. Elbert & Esther T. Mookini, The Pocket Hawaiian Dictionary (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1983)

- ^ Fadiman, Clifton Any Number Can Play 1958

- ^ "Choosing a Lane". California Driver Handbook (PDF). California Department of Motor Vehicles. 2010. p. 33.

- ^ Rose, Joseph (April 16, 2012). "Saturday Night Live's 'The Californians': Traffic's one big soap opera (video)". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Simon, Mark (2000-06-30). "'The' Madness Must Stop Right Now". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- ^ Simon, Mark (2000-07-04). "Local Lingo Keeps 'The' Off Road". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- ^ Simon, Mark (July 29, 2000). "S.F. Wants Power, Not The Noise / Brown rejects docking floating plant off city". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ a b Geyer, Grant (Summer 2001). "'The' Freeway in Southern California". American Speech. 76 (2): 221–224. doi:10.1215/00031283-76-2-221.

- ^ a b Ornelas, Cris (2012). "Kern County Accent Studied." 23 ABC News. E. W. Scripps Company.

- ^ Geenberg, Katherine (2014). "The Other California: Marginalization and Sociolinguistic Variation in Trinity County". Doctoral Dissertation, Stanford University. p. iv.

- ^ King, Ed (2012). "Stanford linguists seek to identify the elusive California accent". Stanford Report. Stanford University.

- ^ Geenberg, Katherine (2014). "The Other California: Marginalization and Sociolinguistic Variation in Trinity County". Doctoral Dissertation, Stanford University. pp. 4, 14.

- ^ Geenberg, Katherine (2014). "The Other California: Marginalization and Sociolinguistic Variation in Trinity County". Doctoral Dissertation, Stanford University. pp. 182-3.

- ^ Geenberg, Katherine (2014). "The Other California: Marginalization and Sociolinguistic Variation in Trinity County". Doctoral Dissertation, Stanford University. p. 200.

- ^ Take Two (2013). "Map: Do Californians have an accent? Listen to some examples and add your own." Southern California Public Radio.

- ^ Guerrero Jr, Armando (2014). "'You Speak Good English for Being Mexican' East Los Angeles Chicano/a English: Language & Identity". Voices. 2 (1): 56–7.

- ^ Guerrero Jr, Armando (2014). "'You Speak Good English for Being Mexican' East Los Angeles Chicano/a English: Language & Identity". Voices. 2 (1): 4.

- ^ https://www.kqed.org/news/11719871/why-the-myth-of-the-san-francisco-accent-persists

- Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (2006), The Atlas of North American English, Berlin: Mouton-de Gruyter, pp. 187–208, ISBN 3-11-016746-8

- Ward, Michael (2003), "The California Movement, etc.", Portland Dialect Study: The Fronting of /ow, u, uw/ in Portland, Oregon (PDF), Portland State University, pp. 39–45, archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-29

Bibliography[edit]

- Vowels and Consonants: An Introduction to the Sounds of Languages. Peter Ladefoged, 2003. Blackwell Publishing.

- Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. Suzanne Romaine, 2000. Oxford University Press.

- How We Talk: American Regional English Today. Allan Metcalf, 2000. Houghton Mifflin.

External links[edit]

- PBS.org: "Do you speak American? − California English"

- Stanford.edu: Penelope Eckert Bolg − Vowel Shifts

- Phonological Atlas of North America

- USC.edu: "A hella new specifier" — by Rachelle Waksler, discussing usage of "hella".

- Binghamton.edu: "Word Up: Social Meanings of Slang in California Youth Culture" — by Mary Bucholtz Ph.D., UC Santa Barbara Department of Linguistics, includes discussion of "hella".